As Lance Armstrong, OJ Simpson and Mike Tyson constantly remind us, not all great stars are heroes, some reputations are forever tarnished. And each time they are, a cherished bit of us dies as well. At least for a while.

Bad Sport is a pungent combination of true crime and sport, compiled and produced with appealing aesthetic creativity, and has been a huge hit for Netflix, strategically intersecting the streamer’s two favourite genres.

They are stories that have little to do with fiction but are so wildly outrageous in some cases they might just have been invented and scripted from someone’s dark imagination. And like so many Netflix documentary films they’re visceral, propulsive and alarming using many of the techniques of straight out narrative fictional cinema.

It’s a six-part docuseries made up of separate 90 minutes films, an anthology series in which each director is empowered to bring a different style and tone, that cinematically retraces some of the most outrageous sporting scandals of the past few decades.

There is scrupulously curated archival footage from the featured games and sporting events, cleverly staged re-enactments that lean towards the abstract used to fill intervals in narrative, interviews with journalists and officials from the period, some contemporary, bringing some temporal perspective, and direct, sometimes highly subjective interrogations of the central figures. The aesthetics of the series are beguiling; it’s a pleasure to watch such an immersive production.

As the series documents so entertainingly, and at times so sadly, money, ego and the single-minded pursuit of success at all costs, of glory really, in these stories is a recipe for the mendacious and the downright devious.

It’s a highly entertaining look at the way stars of different sports have attempted to cheat the system, either for financial or reputational advantage and come undone, some tragically.

The series is from UK production company RAW, which produces an eclectic range of programs ranging from Gold Rush on Discovery, to the delightful Stanley Tucci: Searching For Italy for CNN, to the smash Netflix hit The Tinder Swindler.

Executive producers are Tim Wardle, who created the successful Three Identical Strangers, about the way three brothers discovered each other after being separated from infancy, and Adam Hawkins, who gave as the sensational Don’t F***k With Cats, that compelling story of internet sleuths searching for a serial killer.

Among the stories is an investigation into the allegations that former Juventus director Luciano Moggi influenced referees in a scandal that rocked Italian football; a man called Tommy Burns, a character out of a hard-boiled novel, reflects regretfully on his disturbing days of killing show horses as part of an insurance fraud scheme concocted by wealthy owners.

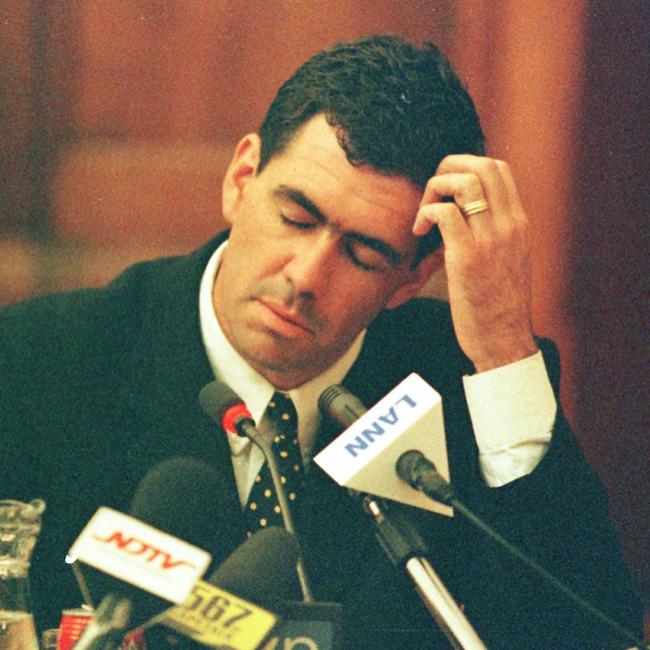

Another character who could have come from fiction, say a Carl Hiaasen novel, is hippie and small-time pot dealer Randy Lanier who funds his passion for auto racing by taking his weed racket to new heights; and perhaps the saddest is that of fallen idol Hansie Cronje, South Africa’s charismatic cricket captain, allegations of match fixing destroying a hero’s gilded reputation.

Some of the films acknowledge the interplay of fate and destiny during life’s most perplexing moments when something beyond the rational seems to have laid its hand on these sports men and women. Entering lives with both limitations and unique talents, destiny plays out in how they creatively incorporate those into the unfolding narrative of their lives. Often with tragic consequences.

Asked to make decisions at these fateful moments in their lives, most choose the wrong one, no matter how right it seemed at the time. For some there seems no real choice; split second decisions have lifelong repercussions on their lives. And on their characters. “Almost all of them are basically about essentially decent people who made bad choices,” says Wardle in a wide-ranging interview at website Newsbreak.

Wardle says that when approached about a series traversing sports and corruption he was obviously intrigued but was insistent he wanted people on the series to come at it from a non-sports background. “I am a really big sports fan, but interestingly, most of the people that worked on the series aren’t huge sports fans,” he says. “I deliberately hired people who weren’t big sports fans, because the best sports stories, for me, are the ones that don’t foreground the sport too much. It’s important, but we were trying to tap into more of the universal themes in this.”

He was surprised to find “almost like Shakespearean levels of betrayal and greed and moral complexity in ways that I hadn’t necessarily thought it would be.” His producers worked from what Wardle calls sports’ “good metrics” – you are either cheating or you are not, the rules are black and white. “And when people start to transgress, there’s a very clear metric for whether they’re cheating or not. Which from a storytelling point of view, is very helpful.”

The first episode, Hoop Dreams, directed in visceral style by Luke Sewell, exposes the famous point-shaving scheme that rocked the Arizona State Sun Devils’ men’s basketball program in 1994. The central player involved, Arizona State’s Stevin “Hedake” Smith, recalls thinking, “Oh really? So you’re telling me, we can win the game, and I can make money? F--kin’ no-brainer.”

Known obviously as “Headache”, Smith was the college game’s biggest star, a monster athlete with fast hands, the team’s playmaker; as a commentator says early in the drama, “This team lives or dies with the man who has the ball – Hedake Smith.”

But he liked to gamble and was soon in debt to the college bookie, Bennie Silman; the only way to free himself from debt was to throw a game. Gambling, a sadly repentant Smith says, “kinda changed everything”.

The point guard “dictates everything on the court, and I got him”, Silman tells the scandal’s financier, Joe Gagliano, who also appears on camera like all the major figures in this sad narrative. “I could not even begin to fathom that Hedake could get the game to land right on six, but Hedake had the skill to make it happen,” says Gagliano. The idea was not to lose outright but to simply lose by an agreed number of points, hence the notion of “shaving”.

As the film argues convincingly the star college athletes never profited from their achievements on the court, the name, image or likeness. Deceit and cheating was inevitable; the game a form of indentured vassalage.

The college players were paid atrociously, trying to live on tiny stipends while millions were made on the games they played. “There were times when I didn’t eat. I would walk to other people in the dorm and ask for something to eat,” Wayne Fontana, another central player in the saga, says.

“We were making the school all that money and we didn’t get compensated at all,” adds Smith. “They were the ones who were behind the scenes with millions of dollars. We were the ones out there on the court.”

Bets were placed on five Arizona State games in Las Vegas between December 1993 and May 1994, and four were fixed successfully. But the word spread, and soon the FBI were involved and Gagliano gets a call from the Feds he didn’t see coming.

It’s a tragic story of skill, insatiable greed and hubris, which led to a lifetime of remorse for the primary players, who are depicted with a righteous proportion of compassion and accountability.

What’s rather extraordinary about the series is the level of access the producers were able to attain to all the key figures, many of whom served jail time, without sacrificing any editorial control.

As Wardle says it’s an antidote to so much sports’ TV controlled editorially by the sports star or their organisation, filmmakers hired to simply technically supervise the production. Here, obviously nothing was off limits, it’s raw and visceral. “And it’s people talking about the worst aspects of sports. Most docs, you see people talking about the best things. So that’s kind of the emphasis, and I feel it’s probably more real because of that.”

Bad Sportis streaming on Netflix

I came across Bad Sport accidentally recently and was quickly hooked, surprised I had missed it before. It’s been around for a while on Netflix and if sport can provide a window into some of the noble elements of the human condition, as this superb series shows, it can also reveal some of the darker, baser aspects of what it’s like to be human. And successful.