Serving the Stasi: a memoir of disturbing family secrets

Imagine growing up in a family in East Germany, in the 1960s and ’70s, in which your father works for the Stasi on secret missions in the West that he will not talk about. Your mother won’t talk about them either. Then the past breaks open.

Imagine growing up in a family in East Germany, in the 1960s and ’70s, in which your father works for the Stasi on secret missions in the West that he will not talk about. Your mother won’t talk about them either. The father becomes abusive on account of the pressures on him, which he can neither share nor resolve.

Then the Berlin Wall is demolished in 1989 and the past breaks open. You get access to an 800-page file on your father’s Stasi career. You discover his secret life. Through your own research and that by others, you learn of how the communist regime in East Germany was set up after 1945 and how it dealt with the Nazi past.

You remember your maternal grandfather as a shrunken, withdrawn old man who was an enigma to you as you grew up. Now you discover he worked for the SS in Riga during World War II, under privileged conditions, close to where the mass extermination of Latvia’s Jews was carried out.

That, too, had been buried in silence all your life. How do you come to terms with it? How do you make a life in a newly reunified Germany? Above all, how do you do so in circumstances where neo-Nazi movements are appearing in Germany and it is plain the dark past has not been resolved or transcended?

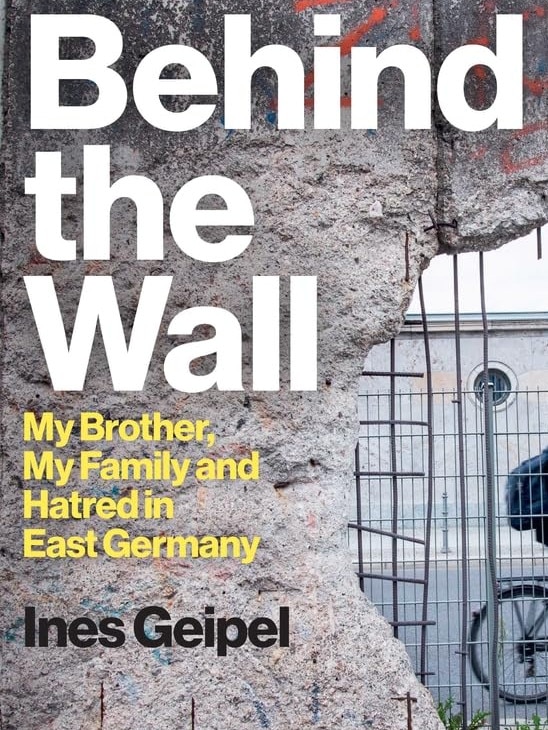

This is the story Ines Geipel tells us in Behind the Wall. And those are just the broad parameters. Born in 1960 in Dresden – famously a city firebombed by the Western allies in February 1945, adding yet another layer of ash and trauma to the family’s past – Geipel grew into a champion athlete, but under East German conditions of manipulation and doping.

Geipel is now professor of verse arts at the Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts in Berlin and a writer. Her book is written in what can be described as a modernist style. It is not a seamless, lucid narrative but is marked by chronological discontinuities, lack of conventional punctuation, staccato phrases, passages that read like inward and traumatic reflection rather than discourse with the reader. It requires careful parsing and close attention.

Her brother Robby, six years younger than her, with whom she had been close in childhood and youth, had wanted to withdraw from the implicit trauma and harshness all around them into a world of artistic imagination. They lost touch for years after she moved west to make a post-GDR life for herself. But in December 2017 she learnt he was dying from glioblastoma, a brain tumour, and she went to be with him back in Dresden.

She begins the book with an account of her conversations with him as he lay dying. That takes her back to their past and the family history that haunts both of them. We learn that, after a decade of serving the Stasi on secret and at times violent missions, their father was retired in 1984 and moved to an undisclosed location. Robby was abandoned by their parents without a word. He came home one day to find them gone and to discover he had been shut out of the family home. Thirty-three years later, on his deathbed, he asks Geipel if she will write up their family story. She had begun her investigation of it as far back as 1992.

She wished, she told him in 2017, that she could forget it. But she cannot. This book is her account of the mental process she went through in writing the present book, in 2018. It was published in German at the end of that year. She tells us of her maternal grandparents, Otto and Elisabeth Grunert, both Nazis from 1933. As soon as Operration Barbarossa began in June 1941, Otto applied to work on the Eastern Front. He was sent to Riga in Latvia at the end of August 1941 to work for the Reichskommissariat Ostland. He was responsible for accounts, budget and staff.

He had a large apartment, a salary triple what he’d had in Dresden, a cook, a chauffeur, a nanny and a summer villa on the beach at Jurmala. And, nearby, in the forest at Rumbula, in November 1941, the SS slaughtered 27,500 of Latvia’s Jews in just over a week. “What did he feel about the orgies of extermination taking place close at hand?” Geipel asks herself and us. “Was he involved? He never talked about it, there is no personal testimony, and mother defends Riga like a crypt. No explanations reach the outside world. The refusal to speak still exists today. There are just the files.”

There is your point of entry to this compelling personal story. It caught my attention especially because in November last year I was in Riga and walked through Jurmala, where there are many fine villas. I visited museums in Riga where the terrors of the Stalin and Nazi years are recorded. Here is someone whose own grandparents and mother were part of that. And there were very many others. History, globally, is full of trauma.

Paul Monkis the author of a dozen books, including The West in a Nutshell (2009) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout