At least Marty McFly went to some trouble to acquire a DeLorean sports car and equip it with a flux capacitor; today’s lazy past-improvers rearrange history from their armchairs.

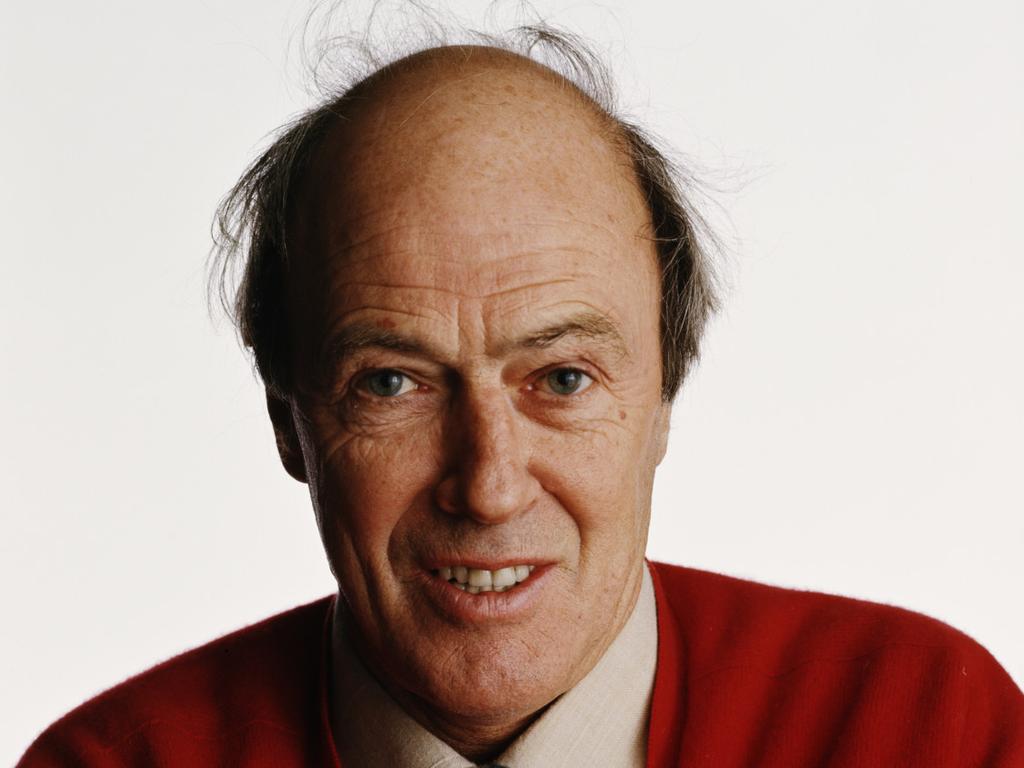

There’s an argument that as sensibilities change, so should the way we address newly delicate subjects. But that doesn’t mean Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl need suffer the posthumous humiliation of their work being rewritten by hyper-touchy morons who aren’t fit to sharpen real writers’ pencils: let what’s written stay written, a snapshot of different times and mores.

Those sensitivity readers are human versions of the algorithms designed by filthy-minded programmers to crawl the net to erase or replace vulgar combinations of letters, with hilarious results. Some US filters turn the word “assassinate” into the gentler “buttbuttinate”. The 80,000 residents of a town in England’s Lincolnshire often find websites refuse to accept their addresses; this kind of unintentional blocking is known in the online world as the “Scunthorpe problem”.

But it’s not all absurdity, nor is it just fictional golliwogs and lard-arse chocolate addicts, however beloved, who vanish from old children’s books; real history, with dates and facts attached, is also reconstructed to kowtow to the edicts of semi-professional offence-takers.

A few months ago I watched the 1955 film The Dam Busters, the story of the “bouncing bombs” that in 1943 shattered the Mohne and Edersee dams above the industrial Ruhr Valley that fuelled the Nazi war effort. Wing commander Guy Gibson, the 25-year-old who led 617 Squadron’s Lancaster bombers in the raid, was awarded the Victoria Cross; he died in action the following year. The film is a British classic, all clipped accents, stiff upper lips, cups of tea and self-effacing heroism, so I was puzzled to see a content warning precede the opening titles. Then as Gibson’s black labrador ran across the screen I remembered why.

Gibson had given him a name that is nowadays unsayable outside the world of rap, but was uncontroversial 80 years ago, as Agatha Christie would attest. The problem for any would-be censors is that the dog’s name was also used as a codeword by the squadron, and is heard many times during the film.

In later US screenings the dog’s name was overdubbed as “Trigger”; when Stephen Fry was contracted to write the screenplay for Peter Jackson’s intended remake he proposed “Digger”. I confess I have no idea why the new name had to rhyme, other than as a subtle nod to the distasteful original. Why not call him Freddie? So while I was pleased the TV channel hadn’t tampered with the soundtrack, it was uncomfortable even to my jaded ears to hear the dog’s name shouted all over the RAF base when he went missing.

Should we all, always, be spared such discomfort? Mark Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn in part as an indictment of the racism of the southern states of the US, and the language and attitudes of many of its characters embody that.

Changing the word he wrote to “slave”, as in recent editions, not only robs his language – and therefore his sense of outrage – of its force; it denies us a contemporary insight into a desperate, and continuing, struggle for dignity and equality.

Nothing new under the sun, though: 17th century poet laureate Nahum Tate rewrote Shakespeare’s King Lear to give it a happy ending, turning one of literature’s greatest tragedies into an Elizabethan soap opera. Now there’s someone who should have been buttbuttinated.

As anyone who’s watched the 1985 documentary Back to the Future could tell you, time travel is a tricky business. And if your plan is to change the past, even for the better, you risk adding arrogance to the dangers of your meddling.