Seafarer’s tale of kith and kin

A new edition of a Scottish classic carries relevance today.

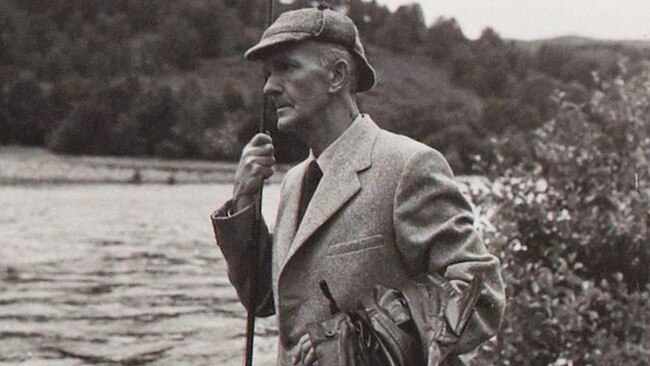

When Highland River was first published in 1937, it won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and a substantial new audience for its author, an improbable literary star. Neil Gunn was born in 1891 in Caithness, the county on Scotland’s northernmost tip. His father captained a herring boat that operated from the harbour of the village of Dunbeath.

Theirs was an austere world — governed by the elements and a narrow set of social strictures — though it was not without beauty and culture. Gunn never lost his love for the sea, or for the men and women who made their lives by it, and he came to know the coastal village and its hinterland intimately.

But Gunn’s academic promise led to him leaving it and his eight siblings behind. He boarded with a family further south for later schooling and eventually landed in London, where he discovered socialism and sex, and passed his civil service exams.

In 1910, he returned to the Highlands as a customs and excise officer.

He wrote a half dozen novels in the decade before Highland River, while active in the Scottish National Party, and joined a circle of writers including Hugh MacDiarmid and Eric Linklater who sought to weld a renascent Scottish nationalism to a left-of-centre politics.

And Highland River is a deeply political book, despite its almost total concentration on the natural world. The sheer quality of attentiveness brought to bear in its pages not only registers a fierce, consuming love of place: it becomes a kind of critique of what has been left out.

Excluded or passed over briefly is the urban realm, gas-lit and squalid, where an inexcusable social inequality is laid bare. The South (in Scotland, the South is a metaphysical region as much as a geographic demarcation: the zone where folk culture has given ground to commerce and power); the twinned authoritarianisms that still ruled Scotland: landed gentry and established church; and modernity in general, with its flabby morality and vulgar materialism.

But most of all the novel represents a wounded reflection on war: its senseless violence, its bureaucratic absurdities and psychological after-effects. Highland River is the account of one man’s return to the river of his childhood in search of some steadying essential wisdom, some cure for the world as it is elsewhere.

Sometimes, though, exposure to what is healthful can be destabilising for a poisoned body. This is why even the most exquisite passages in the book often feel shadowed by what Gunn calls ‘‘a poignancy akin to pain’’.

Kenn, who is both boy and grown man in this narrative, was based on Gunn’s younger brother John, a lifelong friend. A bright boy who ‘‘got on’’ and went South to gain an education in the sciences, John was also a soldier during World War I.

By narrating his brother’s life in a fictionalised manner, but doing so in the third person, Gunn manages the difficult task of borrowing John’s interesting and relatively ‘‘unliterary’’ life while staying present in the text himself.

The result is curious. It is nature writing as inverted polemic: a celebration of place that is shaded by loss. This sense is generated through constant shifts in the time scheme, between young Kenn’s exploits on the river and the experiences of Kenn the mature scientist, a nuclear physicist who has returned decades later to walk that same water, back to its wellspring.

This binocular effect allows the author to ponder the changes the intervening period has wrought: on him, and on the Highland culture into which he was raised.

It is not a heavily plotted book; large incidents are thin on the ground. It consists instead of an aggregation of childhood memories, haunting those remembered spots along the banks and pools of the river, and reawakened by the adult as he moves through them.

‘‘The heath fire and the primrose: the two scents were jotted down by Kenn as simple facts, without any idea of a relationship between them,’’ writes Gunn of the young boy sniffing the air during the heather burning season.

And then suddenly, while the mind was lifting to the cold bright light of spring, to the blue of birds’ eggs and the silver of the first salmon run, there came out of the tangle on a soft waft of air the scent of primroses.

But ‘‘the grown Kenn knows quite exactly one quality in the scent of the primrose for which he has an adjective’’:

The adjective is innocent. The innocency of the dawn on a strath on a far back morning of creation. The freshness of the dawn wind down a green glen where no human foot has trod.

Gunn’s prose can travel on like this for pages: crisp, lingering, alert to beauty and life, any tendency to purpleness cancelled by shifts back to the harsher rhythms and controlled existences of the modern world.

Kenn’s account of meeting his brother Angus in France, during the height of the Great War, after years apart following the older brother’s emigration to Canada, is painful in its reserve. Angus is shot soon after and left in no man’s land.

This is a novel in which nothing much happens, aside from an entire life unfurling inside the head and heart of a man travelling along the river of his childhood.

What is most remarkable about Highland River is that a book so eccentrically formed and privately directed was so well received on first publication.

With its determined meditative strains and its suspicion of modernity, its grief for the loss of an authentic folk culture, Gunn’s novel sits more comfortably in this moment, when ecologically minded fiction and nonfiction has become the most visibly important strand of contemporary writing in Britain.

This new edition comes with an introduction by his nephew, the author Diarmid Gunn.

At a time when Scotland’s place in the world is again in a state of flux, books such as Gunn’s seem more necessary than ever. They are hearth-works, standing at the heart of the culture: a reminder of what was and what can be. And they are bulwarks, too, against broader convulsions of nation and society.

To read the novel is to follow the river to its source alongside Kenn, to find oneself present at the site of some immemorial, ever-replenishing resource. In a damaged world, the author has led us to one point that is entirely pure.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Highland River

By Neil M. Gunn. Introduction by Dairmid Gunn. Canongate, 256pp, $19.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout