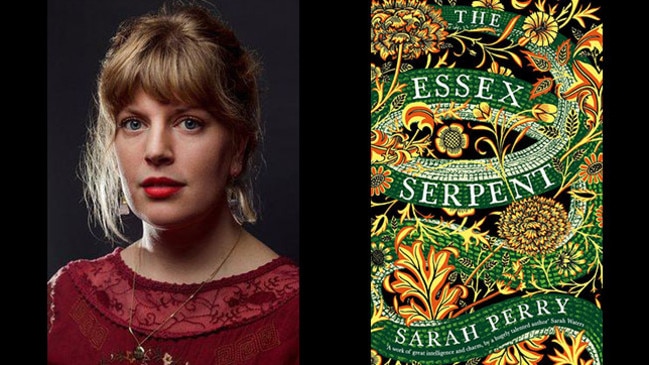

Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent mirrors ferment of the times, and ours

Agile, unconventional and wonderfully weightless, Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent is a delight.

Sarah Perry’s first novel, 2014’s After Me Comes the Flood,was an oddly unclassifiable creation about a man lost in an unsettled, dream-haunted version of the English countryside.

Distinguished by Perry’s strikingly assured command of language and theme, the book was eerie and fascinatingly unresolved, conjuring influences as various as MR James and Franz Kafka. It managed the not inconsiderable trick of seeming utterly contemporary and strangely timeless.

Perry’s new novel, The Essex Serpent, shares some of this unclassifiability, suggesting comparisons with Edgar Allan Poe and Bram Stoker, as well as more contemporary reworkings of the 19th-century novel by writers such as John Fowles and Sarah Waters. Yet its intellectual exuberance and playfulness are such that it never feels derivative or belated.

Set in the dying years of the 19th century, the novel is largely focused on three characters: the recently widowed Cora Seaborne, clergyman Will Ransome and the brilliant surgeon Luke Garrett.

Around these three move others: Cora’s son Francis, who is autistic (and, one suspects, somewhat sociopathic); her companion Martha, who is a working-class socialist; Will’s beautiful but tubercular wife Stella and their children; Luke’s devoted and long-suffering friend George Spencer, who is good-hearted and rich; and Conservative politician Charles Ambrose and his wife Katherine.

Coiling around them all, never fully glimpsed or explained, is the serpent itself, slithering just beneath the surface of Essex’s Blackwater Estuary. Perry was born in Essex.

As the novel opens, Cora is emerging from the nightmare of her marriage to Francis’s brutal and controlling father, a relationship that has left her scarred inside and out. Seeking to recover some sense of the person she was before her marriage (and to keep her lack of grief over her husband’s death from becoming evident to London society), she moves to Essex with Francis and Martha, where she is free to indulge her fascination with science, particularly fossils.

As she arrives the region is electric with talk of the Essex Serpent, a creature of myth that has recently reappeared, and is believed responsible not just for the death of livestock but that of a young man found drowned in the Blackwater, his head twisted 180 degrees, his eyes staring in horror.

Thrilled by the possibility that the serpent may be some kind of biological relic of another time, a creature of the Palaeozoic that has somehow survived, Cora is induced to the town of Aldwinter, where she meets Will and, without ever quite realising it is happening, falls in love with him.

Although the relationship between the determinedly unconventional, scientifically minded Cora and the more conventional Will — and their startled realisation that they are in love — forms the emotional heart of the novel, it is counterpointed by a series of splendidly realised subplots. These involve Martha and George, the otherworldly yet sensual Stella and most particularly the intellectually and personally ferocious Luke. His preparedness to push the boundaries of surgical convention provides a striking scene where he opens the chest of a stabbing victim and repairs a tear in the pericardial sac, an act that later leads, via a series of misunderstandings, to the novel’s most viscerally distressing moment.

Neither the collision between science and religion nor the possibilities of the gothic and the eerie to reveal how the certainties of religion have been displaced are unworked ground (Frances Hardinge’s The Lie Tree and Andrew Michael Hurley’s The Loney are recent examples of both). Yet The Essex Serpent explores its material with such energy that it always feels fresh. Like After Me Comes the Flood, it is also delightfully unconstrained by the influences moving beneath its surface, its playfulness permitting it the space to be aware of the tradition in which it operates, yet also entirely contemporary in its manner.

In places this can be a little disconcerting. Certainly there is a curious lack of interest in how class shaped and constrained interpersonal relationships in the period, something that is particularly obvious in the behaviour of the supposedly working-class Martha. Yet it is also fascinatingly liberating, at least partly because one never doubts that even if the novel elides them somewhat, Perry is fully aware of the complexities of these questions.

The result is a novel that somehow embodies the exhilaration and ecstasies — of body and mind — its characters stumble into, suggesting not just the ferment of its times but something of the ferment of our own. And, no less impressively, it exults in the possibility that inheres in the liminal spaces that its titular serpent inhabits — between land and sea, old and new, even life and death. Agile, unconventional, wonderfully weightless, it is a delight.

James Bradley’s most recent novel is Clade.

The Essex Serpent

By Sarah Perry

Serpent’s Tail, 432pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout