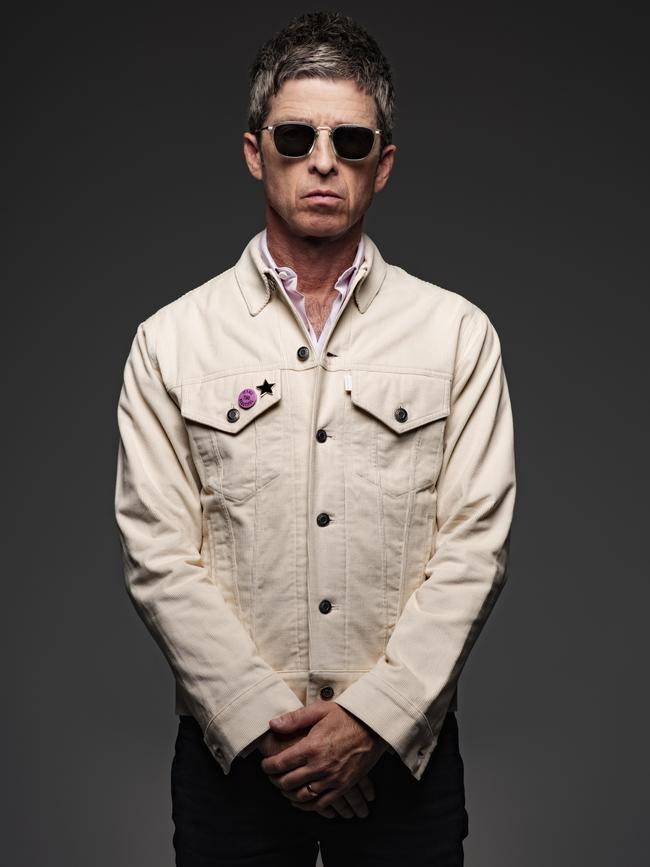

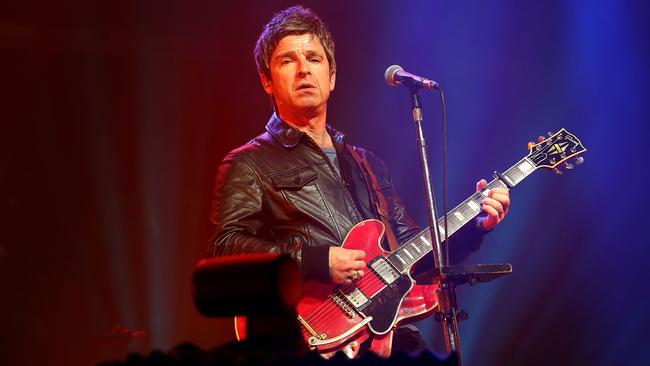

Rock legend Noel Gallagher on the only time he was left speechless

After Oasis disbanded in 2009, songwriter and guitarist Noel Gallagher started a solo project, High Flying Birds — but why was rock ‘n’ roll’s biggest mouth rendered speechless?

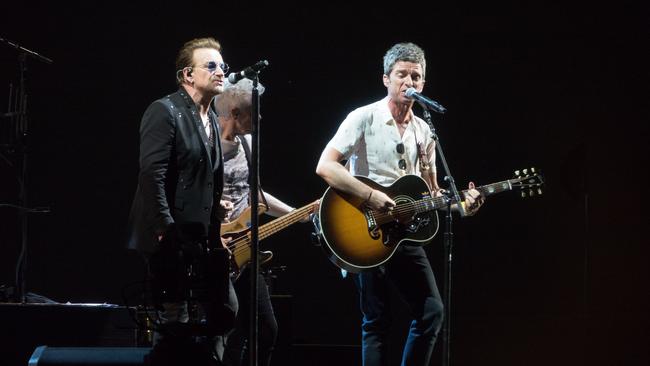

The last time I saw you, Noel, you were on stage with your band inside a stadium here in Brisbane. What do you recall of supporting U2 on that tour?

It was great. I did quite a chunk of that world tour, and Australia was great. When you’re on the road with 150 Irish people, you don’t really tend to recall any of it. There’s a lot of, ‘Where are we now?’ kind of thing. But suffice to say, we had a great time. The crowds were great, and the lads – U2 – were great. It was a nice trip.

When that sort of offer is brought to you, is it an easy ‘yes’?

It’s easy. In fact, for that Australian tour, I think I might have asked them. I was out one day having lunch with (U2 guitarist, The)] Edge, in a restaurant here in London. He was telling me he was going to Australia in November, and I said, ‘Oh, no way, my touring schedule finishes at the beginning of October. I’m around. Can I come?’ Funnily enough, he just said, ‘Yeah,’ and that was it. If only life was that easy.

Before you go on stage in a big venue like that, who are you thinking about playing to: the people at the front? The back row? Somewhere in between?

Well, I would imagine that a fair chunk of a U2 crowd would be sympathetic, let’s say, to the sound of what I do. Oasis and U2, apart from the attitude, were not too far apart. We’re all Irish; we’re stadium rock. It’s not too dissimilar. So we just treated the whole thing as a holiday, really. The sun was shining, and some of the band had never been to Australia; they were loving it. And you get to see one of the greatest bands of all time every night, and get paid. Not bad.

With the biggest screen ever made by humankind behind them on the stage…

It’s literally the hottest place on Earth. You can get a sun tan.

Was there a point in your life where that sort of thing – playing in front of massive crowds – became just another day at the office for you?

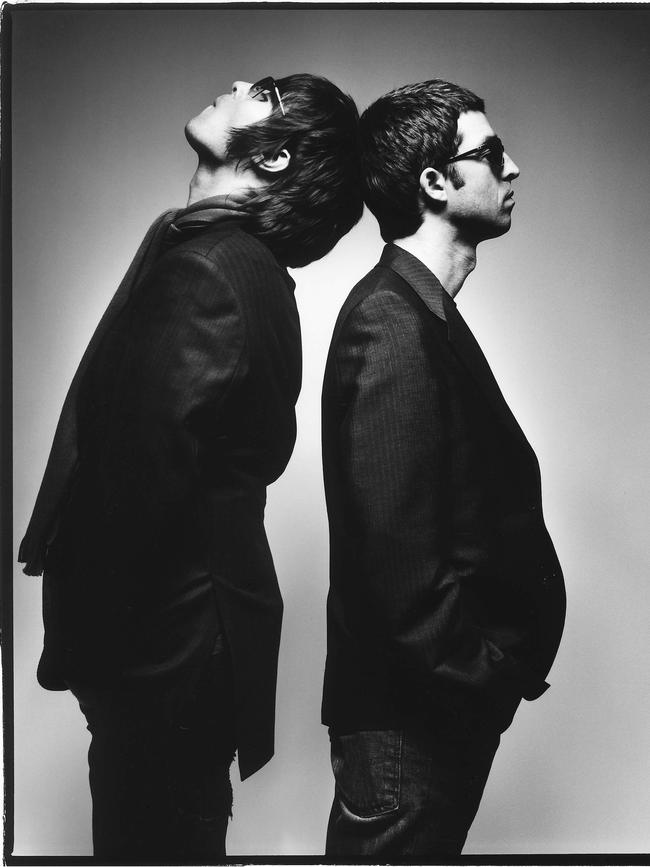

Let me see: we started doing stadiums in ‘95, and went all the way through to 2009. Yes, you do get used to it but, no, I never took it for granted. I always felt it was a privilege to be on stage watching 60,000 people having a night out, and you’d be the soundtrack to that. I never used to get nervous at all. Those gigs used to bring the best out of me, and there’s not many people who can say that; some people have a real fear of it, but they brought the best out of me, and anyone that’s seen us will confess to that.

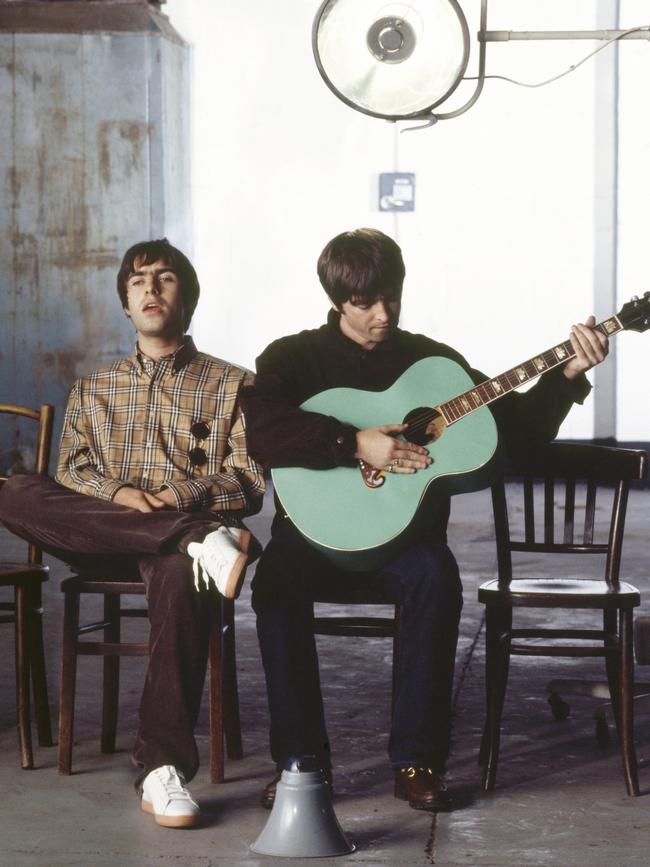

I enjoy everything that I do; there’s no point in doing it if it’s a struggle. You know, that’s why Oasis is not together, because it became a struggle. And it’s like, ‘Well, f..k this; this is supposed to be a laugh, and easy’. What I do now is a thousand per cent more enjoyable than what I was doing then. That should be the basis of your life: if it makes you feel good, do it. If it makes you feel shit, don’t do it.

Can you describe the feeling of a stadium full of people singing along to something that you wrote on your own in a room somewhere?

It’s like being high, but you’re straight. It’s the highest high, but you’re completely aware of where you are, and you’re in the room with the people. There’s a fine balance of that to strike, though, because there’s 50,000 people having a night out in a stadium, watching five guys at work. You don’t really want to be having a night out, because you can’t do your work properly. So there’s a balance that you have to achieve, which I felt like I did most nights. But it’s a real spiritual thing. Everybody reacts differently to it: some members of my band used to feel physically sick before they went on. I was completely the opposite. But it’s quite a religious experience. Once the initial nerves at the start of a gig (went), and everybody’s relaxed and they’re into it, I used to specifically try to take a step back and just take it all in. I knew I wasn’t going to do it forever.

Near the end of that set you played (the Oasis song) Don’t Look Back in Anger. It made me emotional because it reminded me of how that song was used as a kind of public service following the bombing in Manchester in 2017. Tell me if you don’t want to talk about it, but if you’re up for it, what do you recall of how that all played out from your end?

Well, the night of the incident, I happened to go to bed early. My phone started buzzing a lot more than it would do. I looked at it and there were messages from my friends all over the world saying, ‘I hope your people are all alright’. I put on the news and of course there had been a bomb, and an awful tragedy. But when the girl started to sing the song in the memorial service, your feelings are conflicted: you’re incredibly proud that something you did has become some way of helping people through this, but then it’s attached to a real tragic event. So you can’t get too big-headed about it, because let’s not forget, people died. It’s a two-way thing, really. It’s just amazing that a song – any song – could bring people together. The fact that it was my song makes it doubly amazing. Sitting down and thinking about it, that’s kind of what my songs are: they are inclusive. They’re not about me, and they’re not about you; they’re about us all. It’s a wonderful thing, albeit attached to a very tragic event.

Why do you think people reach for their favourite songs in that sort of situation, following a tragedy?

Because they somehow – whether it be the melody, or the words – they can somehow make sense of it all for people. I’m not sure; you’d have to ask somebody specifically. But music for me is such an important, powerful, religious, spiritual thing. Why do people sing hymns at church? It must be in the human psyche to sing, and to project something outwards. So yeah, it’s amazing that that just spontaneously started; one girl started singing it, and everybody joined in. It was an amazing moment.

What did seeing that mean to you at the time?

Well, I happened to be watching it live on television. I’ve only ever been speechless four times in my life: at the birth of my three children, and that. You don’t know what to feel. Initially, you’re feeling, ‘Oh, f..king hell, no way!’ And then you kind of wish it wasn’t happening. You wish that the square was empty, and life was just going on as normal. It was conflicting emotions.

Where does that particular episode sit among everything you’ve achieved as an artist in your life?

With that particular song, it’s an ongoing thing. The song was used as well as during the Paris attacks (in 2015); at the football that happened two nights afterwards, a band played Don’t Look Back In Anger. It’s sad that it has to be used to bring people together at all, during tragic events. But it obviously helps people deal with whatever trauma they’re going through, and it’s all good by me. I’m not complaining about it. But there’s certainly… I don’t know. I find it hard to articulate it – which is not like me. I can usually articulate most things. But that’s a tough one.

We’re talking today because it’s coming up 10 years since your debut album with your band, the High Flying Birds. Are you searching for something different in the songs you’re writing today, compared to those for the first Birds album?

Well, I tend to write more in the studio now than I would at home. So when you write in the studio, you have access to more instruments. You don’t have to sit home and think, ‘Maybe if I put a drum machine on that…’ – you can do it instantly, so ideas are formed instantly. I guess the essence of what I do is still the same: it’s all about the melody. The melody is the thing. The words? Ehh, who cares about the words? And then, if I come up with an idea, if I’m lucky enough I’ll be able to turn it into a song. I’ll get a few of those ideas together, I’ll get the band together, and then we all gang up on the idea. Eventually, it falls into a High Flying Birds thing – but the scope of the musical output of the band is a lot wider now than it ever was in Oasis.

Is that because your horizons have expanded as well? You seem to be more interested in lots of different genres.

It’s not down to one specific thing. Oasis was a band that had a very clear identity of what it was and what it should be. I wrote songs to suit the surroundings, which were stadiums. You’re not going be doing a jazz odyssey in a f..king stadium full of young lads with their tops off; you’d get f..king lynched. But when I met (producer) David Holmes, he suggested, ‘You’ve done everything you could possibly do with that acoustic guitar – why don’t you try and start making the music that you actually listen to?’ That’s what I did, and that’s where (2017 album) Who Built the Moon? came from. And now I try and marry all the ideas that I’ve got. I still write at home, but I do write in the studio. Some things like (recent single) We’re On Our Way Now sounds like a very traditional Noel Gallagher tune. But the song is so good, and that’s the way it came out. I’m not running away from that. Then the other track (Flying On the Ground) could be The Supremes singing a Burt Bacharach song. Everything’s on the table.

What’s your sense of how your songwriting muscles have strengthened over the years?

I’m really more relaxed about it. I think that streaming, in a weird kind of way, has been good for creativity. Because if nobody buys records anymore, then you don’t have to try and sell records. You can just f..king please yourself, do what you want, you know? In that way, it’s been quite liberating. But it’s an instinctive thing: I couldn’t explain it to you, but I know when something is good, and it’s usually the melody. If I come up with a melody that makes me keep going back to writing that song, and keep chipping away at it, then it would lead me to believe that I’ve done it so often in the past that this must have a certain level of goodness to it.

Early on with High Flying Birds, were you worried or concerned that fans of your earlier work and earlier sound might not come along for the ride?

Well, believe you me, a sizeable chunk of them didn’t (laughs). I might have been the only person in the world who wasn’t surprised by that. If I’d have thought I would have left Oasis and gone on to still be playing stadiums with High Flying Birds, I wouldn’t had f..king bothered. I didn’t want that. I’d been doing that for the previous 20 years. I wanted to start at the bottom, but it got really big really quickly. I’ve been kind of backing away from that ever since, because I’ve done stadiums, and they’re great, and I’ve loved it – but that’s a part of another life, almost. I’ve done big arena tours, and they’re great. I loved that, too. But I never really got to do theatres with Oasis, because we went from nightclubs to stadiums in about a week. So I’m doing the thing now that I never got to experience, with a big band that’s multicultural; everybody brings a different vibe to the table.

I asked about your songwriting muscles; what about your performance muscles? Was there much of an adjustment required to get these Birds songs across live?

I must say, performing is the least favourite part of what I do. And the older that I get, the more I can’t be f..king arsed.

Is that to do with being away from home?

Well, creative people are always away from home, because they live in their imaginations. I do like doing it, but I wasn’t born to perform. (U2 singer) Bono, for example. I am probably the opposite of a Bono. Bono wants everybody to have a great time. I don’t really give a shit if anybody has a great time; I’m just there to sing the songs, and hopefully people will get us. I have a love/hate relationship with performing.

All three of your High Flying Birds albums have gone to No.1 in Britain, making it 10 albums in a row for you all up …

That’s a world record, did you know that? Ten No.1 albums in a row in England is in the Guinness Book of Records. No-one can match that. No-one.

Congratulations – that’s an awesome achievement.

Thank you very much. If only my f..kin’ wife would be remotely as interested as anybody else …

What does that sort of record mean to you?

Well, it gives me the confidence to go and do another one, but I guess the streak has got to end at some point. I don’t think about it; I actually wasn’t aware of it until somebody told me and I got an award for it. But it means that my songs down the years have been accepted by a lot of people. I still play the old stuff when I do play, and they go down as well as they ever did; probably more so now. I try not to think or over-think anything about what I do; I just kind of do it. The benchmark is: do you enjoy it? Yes? Right, then let’s move on and do something else.

You were one of many British artists to recently put your name to an open letter about how Spotify and other streaming platforms don’t pay their fair share to musicians. Was that an easy ‘yes’ for you?

Absolutely, yeah. I didn’t even read the f..king letter; the guy just told me what was in it, and I said, ‘I’ll get on board with that.’ But yeah, streaming doesn’t pay much … you know, the f..king guy that owns Spotify (Daniel Ek), he’s now saying he’s going to buy Arsenal. With my money! With my f..king royalties! If he buys Arsenal, I will go down and strip one of the restaurants of all its f..king furniture, ‘cause he owes me, that c..t. But music is now not for sale, it’s for hire, you know? I’ve never been comfortable with the idea. I grew up in a generation that owned music. And the quality of Spotify is shit. It sounds shit; it’s a bad representation of what your music is. It’s a fight none of us can win, so there’s no point boycotting it. But the government, should look at it, will probably see it’s grossly unfair. But I doubt the government will do anything; they’ve got other things on their mind now.

What else have you observed about the changing nature of the music industry between back when you started and today?

There’s the fact that I’d say a good 80 per cent of the charts, the artist in question probably doesn’t write their own songs. That’s been a big shift. A lot of the smaller and medium-sized venues have shut down in England. And the internet, which of course has affected everything, and has had had a negative effect on everything creative in the world.

What a downer. Sorry.

Well, that’s all right. That’s just the way it is. Everything is fake on the internet; the only thing real is the f..king hate and the division. Everything else is just f...ing bullshit. But it’s the world in which we live, so old guys like me are not going to be listened to by anybody. So f..k it. I did all right out of it, and I tend to do all right out of it. If people didn’t f...ing subscribe to Spotify, it wouldn’t exist. There’s obviously an appetite for it, so f...ing crack on. But we, the artists, I can assure you feel a little bit pissed off. But everybody’s going to be like, ‘Really? How many f...ing private jets do you want?’ To which I would say, ‘Just one would be nice.’

You’ve remained productive and active into your 50s. Which other artists do you respect for having maintained a positive creative output into their 50s and beyond?

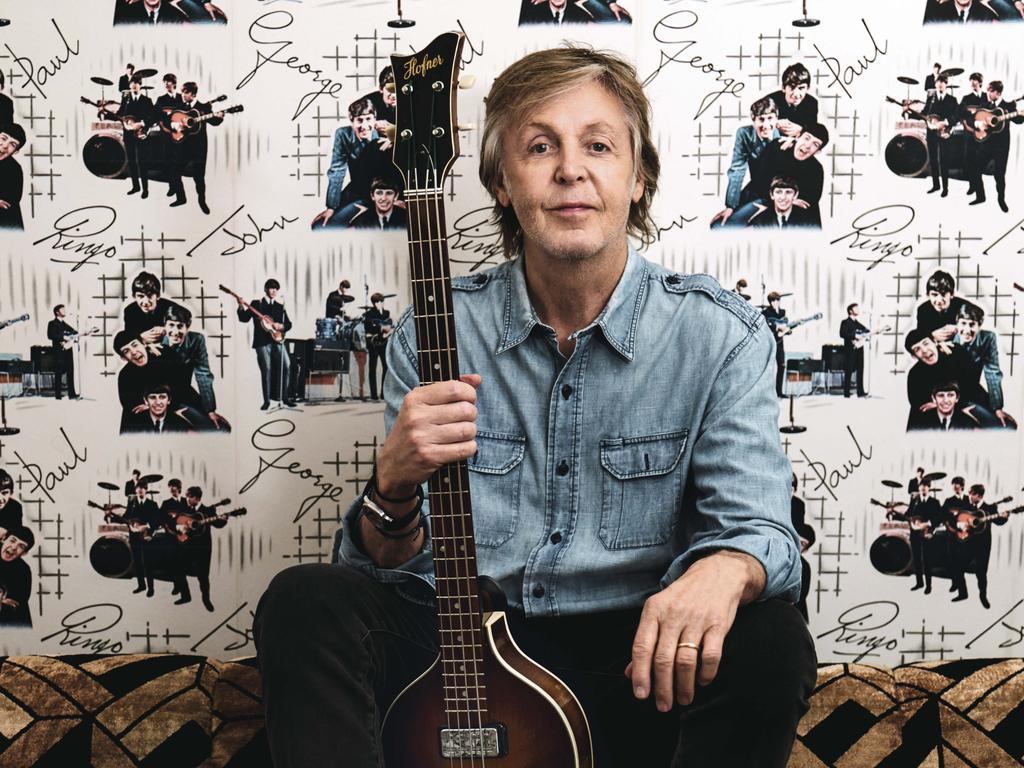

I think the main one is Neil Young, who just doesn’t give a f..k, still, to this day. I went to see Neil Young with Bob Dylan a couple of years ago in London; they did a co-headline gig. Bob Dylan is mad as a f...ing brush, but Neil Young has still got the fire. He’s great. McCartney’s still doing great stuff. My mate Paul Weller, f...ing hell. I don’t even know what to say about him. He’s probably writing his fourth album today, right now. On my last world tour, I was doing Roskilde Festival in Denmark, and I was second on the bill to The Cure. They’re one of my favourite bands, but I’d never seen them in all my time. I was lucky enough to be allowed to stand on stage and watch them perform, and they were absolutely incredible. Those guys are all older than me, and they still sound f...ing unbelievable to this day. And of course, it goes without saying: U2. All the greats are great for a reason – ‘cause they’re great.

I’m glad you mentioned Paul McCartney, who’s still putting out interesting new stuff at 78. Do you find that inspiring?

Absolutely, of course. Why would you stop? I mean, the only thing that would physically make me stop making music is if somebody chopped one of my hands off. Other than that, as long as I can get a tune out of something, I’ll be compelled to write a song. But McCartney, god bless him; I’ve seen him live a couple years ago, and he was just the best he’s ever been. He doesn’t change any of the keys (when singing); usually, old guys start to bring the key down a little bit. McCartney’s still going for it. What a dude. But he’s one of The Beatles, and they are the greatest of all time for the simple reason that the four guys in it were just amazing.

Lastly, can you name an active musician who’s massively underrated that people should pay more attention to?

Apart from me? Not a musician, but there’s a band from the UK called Young Fathers. People should pay more attention to them.

Back the Way We Came: Vol 1 (2011-2021) by Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds is out June 11 via Sour Mash Records.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout