Robert Hughes: the genuine article in The Spectacle of Skill

The new material in a collection of Robert Hughes’s writings is raw, courageous and hard to read.

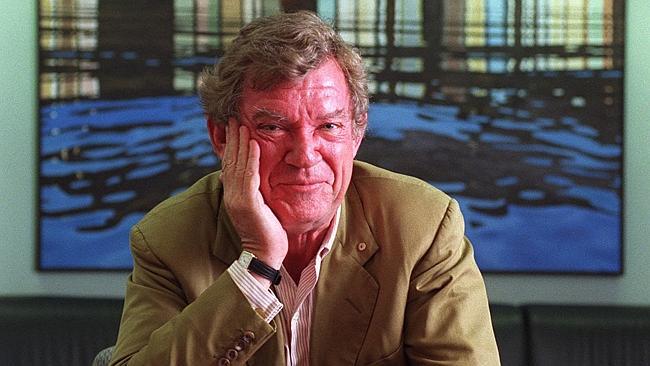

The only time I met Robert Hughes he was in Sydney and had agreed to be interviewed in the office of Edmund Capon, the then director of the Art Gallery of NSW. It was 1996 and the interview was to promote an exhibition of modern art from the William S. Paley Collection at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Hughes had nothing to gain by promoting it. He agreed, I assume, as a favour to Capon.

He had just completed American Visions, his excellent, 600-page history of American art. But the effort had cost him, plunging him into a severe depression. I didn’t know this at the time and could not have guessed.

In response to my questions, he was warm, brilliant, and generous. He was prickly only once, when I concluded the interview by asking him what new project he was working on. “Come on, mate,” he said — and here I remember a micro-expression of anger and pain, like a Francis Bacon smudge, flash across his ruddy face — “Give me a break. I’ve only just finished the last one.”

He tried, too late, to season his indignation with an ironic grin. But I had seen that expression, and I felt chastened. How many books had I managed to write?

I accompanied Hughes downstairs, where a newspaper photographer was waiting to take his portrait. As the photographer set up, a woman approached him, explaining she was there with a bunch of students who were too young to know who he was, but would he mind coming over and saying a few words to them?

Hughes didn’t hesitate. He strode over (he was not yet the hobbling wreck of a specimen he became after that horrendous 1999 car crash in Western Australia), and immediately had the gaggle of seven and eight-year-olds in the palm of his hand. He received the thanks of their teacher with ease and affability.

Wow, I thought afterwards, skipping across the Domain. That was impressive. All of it.

To describe Robert Hughes as the liveliest, most influential art critic Australia has produced has always seemed to sell him short. He was so much more. Those of us who envied his impact on the conversation around art were reduced most of the time to pretending he wasn’t also a brilliant popular historian, a polemicist, a critic-at-large, and even a congenial memoirist.

And yet most of Hughes’s energies did in fact go into writing about art. The Spectacle of Skill — the title is taken from a frothy salvo in which he defends his idea of elitism — presents an overview of his writings. It is introduced, with affection and insight, by his friend Adam Gopnik, a staff writer on The New Yorker.

Along with excerpts from The Shock of the New, his brilliant 1991 introduction to 20th century art, this book includes essays from Nothing If Not Critical (1991), the indispensable collection of reviews he wrote as the art critic for Time magazine, and extracts from American Visions (1998)and his 2005 biography of Goya.

Also represented are Hughes’s big, beefy books on Barcelona and Rome; the first volume of his memoir Things I Didn’t Know; A Jerk on One End, his little book about fishing; and The Fatal Shore, his history of the colonisation of Australia and probably his best-known book.

All this is pure pleasure. What Hughes had — the quality that distinguished him from all his peers — was appetite. Appetite for knowledge. Appetite for argument. Appetite for experience. He had a brilliant feeling, too, for narrative propulsion and an unmatched ability to convert sensuous experience (and especially visual experience) into brilliant, vital prose — prose that popped.

The Fatal Shore, besides being a well-paced yarn, has some of his best descriptive writing. Banksia bushes boast “sawtooth-edge leaves and dried seed-cones like multiple, jabbering mouths” while eucalypts have “their strings of hanging, half-shed bark, their smooth, wrinkling joints (like armpits, elbows, or crotches), their fluent gesticulations and haze of perennial foliage”.

And of course, inserted in the right place, such arresting specificity serves a larger purpose: the reader, along with the arriving convicts, gains a sense of the very specific strangeness of this new land.

The proximity of so many different kinds of writing in this volume invites us to ask how Hughes’s broader talents — his great polemical gift, his deep interest in history, his love of great cities and his passionate interests in carpentry and fishing — inflected the tenor of his art criticism. One answer is that it made him immensely cosmopolitan. His urbane yet bracingly indecorous voice was a salutary antidote — and a challenge — to the polite parochialism of so many New York critics.

But another answer is to acknowledge that Hughes’s polemical instincts often got the better of him, so that even as he was writing with acumen and prescience about phenomena such as the galloping art market, the “victory of promotion over connoisseurship” in the art world and “the decay of the fine-arts tradition in American schools”, he could be wincingly kneejerk in his conservatism and, at times, almost wilfully uninterested in philosophical subtleties or nuances of feeling.

He became, like most people, more conservative as he aged, and more impatient with folly. There was no shortage of folly in the art world. But Hughes preferred to return to the same soft targets (Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel) long after it appeared useful to do so.

He was, in the final analysis, a moralist — a good Jesuit boy — whose crusading instincts tended to overwhelm his receptiveness to new experiences. He was wrong, I believe, about there being a dearth of great art today. He was too appalled by the superabundance of bad art to notice it.

Missing, sadly, from this collection is anything from his great book on the British painter Frank Auerbach, and anything from The Culture of Complaint, his rousing 1993 polemic against follies on both sides of the political spectrum in the US.

What is new is a series of disconnected chapters Hughes wrote for the second volume of his memoir, which was left unfinished when he died, too early, in 2012.

There is something intrinsically sad about these personal essays. It’s not just their curtailed and disconnected nature, but the whiff they give off — for which it seems entirely unfair to blame him — of overwriting, under-editing, spleen, and sentimentality. I think Hughes was tired. I know he was in pain. Pain makes you touchy, irascible, and indifferent, perhaps, to reproach. (On the other hand, even in his pomp, Hughes was never remotely afraid of making enemies.)

Among the material from the unpublished memoir are two surprising chapters. One, titled “Graft — Things You Didn’t Know”, is an eye-popping expose of the sloppy ethics of several prominent art critics, including the hugely influential British critic David Sylvester. But it begins with a long takedown of Clement Greenberg, the American critic who was the first to champion Jackson Pollock and whose terse, imperious judgments and spurious theories did so much to shape postwar American art.

Hughes describes Greenberg, accurately, as a “mediocre writer” and “by nature a bully”. He also points to his heavy drinking, which worsened over time, and his long involvement in Sullivanianism, a therapeutic cult that regarded the nuclear family as the root of mental illness and therefore championed non-monogamous communal living — with consequences for the children of its members that were often disastrous.

“All parental relations were stigmatised,” writes Hughes, “as inherently ‘destructive’. (Greenberg, for this reason, refused to have anything to do with his own son, who had been born in 1935.)”

To read this, and then proceed to Hughes’s heartbreaking chapter on his own estranged son, Danton, a sculptor who committed suicide at the age of 34, is discombobulating.

Danton’s birth, writes Hughes, “brought me immeasurable hope and delight in the midst of a union whose front was not altogether united”. He goes on to honour his lost son with a series of intimate recollections, tenderly expressed. But in more than one place, the prose reads as if it were by somebody else. It is awful.

“Alas,” writes Hughes, “this beautiful boy would be witness to more of the acrimony that pervaded the landscape of our weak spines, hanging on rootless trees.”

Trying to answer the question of why Hughes, unlike his son, had managed to resist suicidal impulses even at his lowest ebb, the rifle “firmly in my grip”, he asks: “Could it have been the peony that bloomed in earnest on that warm spring day, so eager to live the short life of limitless petals folding into one another spreading sublime beauty into the eye of the beholder, who was me?”

One wants to sneeze. But of course the weakness in the prose is a faithful index to Hughes’s pain, his inability — which would be any parent’s inability — to get his head around such an intimate catastrophe.

Confessing that past soul-searching had always led him to the conclusion that “it was never my fault”, he now freely heaps blame on himself: “how could I explain my role as a father who knew nothing of how to be a male figure of strength to my only child when I was living a life that was comprised of infidelities, booze, my responsibilities as a card-carrying member of the New York literati, and mired in a marriage with an equally challenged partner … ?”

It is hard to read these groping, raw, uncomprehending, and yet courageous pages. Better to turn back to the earlier pages about Long Island, or the author’s long friendship with Robert Rauschenberg, or his wonderful essays on John Singer Sargent, Frank Lloyd Wright, or Edward Hopper.

Writing such as this — humane, informed, approachable, sensuous, honest, exuberant — takes a special gift, and a remarkable, magnanimous personality. It is incredibly hard to pull off. It’s not surprising to learn that it cost him.

Sebastian Smee, art critic at The Boston Globe, is a former national art critic for The Australian.

The Spectacle of Skill: Selected Writings of Robert Hughes

Introduction by Adam Gopnik

Random House USA, 688pp, $79.99 (HB)