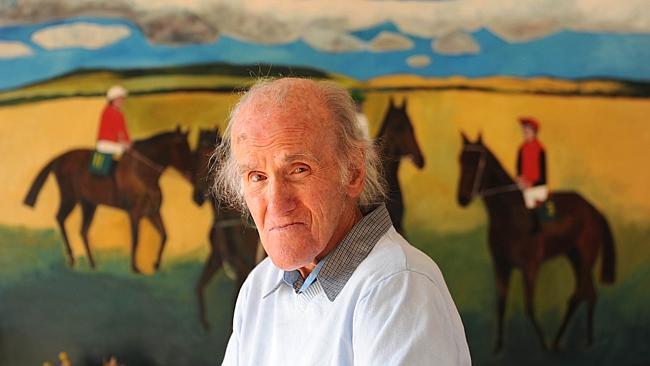

Robert Dickerson: for the love of art

NINETY-year-old artist Robert Dickerson, ahead of a major exhibition of his work, reveals the secret behind his longevity.

EVERY afternoon, the scene is the same. As the sun starts to fall across the mountains, Robert Dickerson can be seen walking along his racetrack, deep in thought.

There are two tracks for horses on his property: this is the longer one, stretching over 2400m, the length of the Caulfield Cup. He walks three laps around, and the whole circuit takes him almost two hours to complete. It’s a reflective time of day, around dusk at Cambewarra, near Nowra on the NSW south coast, and Dickerson, usually wearing a soft white hat, takes in the shifting colours of the light in the trees and hills in the distance as he takes his daily walk. “It’s a good time to go through your mind,’’ he says. “To relax.”

Dickerson turned 90 at the end of March, and his exercise routine rarely varies. His days inside a boxing ring are long gone but his fitness level remains high. There are the weights and the squats, plus walks, and he often swims in the pool beside the house. The view from the pool is a seductive one and he talks with affection about the way this landscape plays on the eye.

PHOTOS: A gallery of images from Robert Dickerson’s life

“The effect of the environment here means you’ve got a permanent entertainment,” he says. He looks up, gestures into the distance. “That mountain changes all the time. The whole place changes all the time.”

Dickerson, not usually one for sentimentality, takes a moment to reflect on his surroundings. Much has changed, much remains the same. His passion for horseracing goes back to when he was a teenager, when there wasn’t much money to spare but the chance to earn plenty more. When he began painting, he was doing it just for himself, and his pictures carried that same quiet, solitary mournfulness they do today. He remains something of an outsider, and while he’s well represented in major collections across Australia, there’s a sensitivity among his family about the need for a retrospective, whether he has received due recognition from his home state of NSW after all these years. Even now, on the eve of a new show in Brisbane, with Dickerson standing as one of the elders of Australian art, the only member of the Antipodean group of 1959 still close to the top of his game, he continues to struggle with the challenges of his art.

“All painting is a terrible thing, really, if you’re really serious about it,” he says. “You paint a painting and you think it’s marvellous, and lo and behold you go back and see it and it looks lousy.”

It’s why Dickerson often destroys work he doesn’t like. He might put all his effort into a painting only to find it “pretty dreadful” when examined later. An artist needs to be “very stern about what you put down”, he says, which sometimes means painting over something and moving on.

“Being an artist, you’ve got to be in love with it,’’ he says. “You’ve got to be critical too.”

A CHILD of the Depression, Dickerson worked hard from an early age. He spent hours after school in his family’s backyard factory in inner-city Sydney, making tin mirror backs and distributing them around town. Before long he was working in a factory in Annandale, earning 16 shillings and sixpence for a 44-hour week. He was working out on the side and turned to boxing, with his first fight at the age of 15. In the ring he took on the name Bobby Moody after a successful fighter abroad. The fights were often fixed, which meant more money, since the fighter could earn extra cash by betting on the winner. He also travelled with Jimmy Sharman’s boxing troupe around the state. But his boxing career came to an end after 37 fights, and Dickerson is far from nostalgic when he thinks of those days in the ring, or the sport in general.

“I don’t rate it at all,’’ he says. “Anybody who goes to see and watch some poor bastard get knocked about, no, I don’t like that.”

He liked the track, though, and an enduring passion for horseracing was set in train. Sometimes he’d see his father at the races, though it was far from a bonding experience — they travelled separately and spoke only once at the track. He explains: “I happened to back a 19-1 winner up at Warwick Farm. He knew I’d backed it. And he went broke and borrowed money off me. His horse won so he gave me the money back straight away. About the only time he ever spoke to me.”

War broke out and, still a teenager, he joined the RAAF. He found himself based on the Indonesian island of Morotai when World War II ended, reading The Moon and Sixpence, the Somerset Maugham novel loosely based on the life of Paul Gauguin. He drew portraits of local children while waiting to return home.

His ambitions remained modest. “I never thought of being an artist,’’ he says. “I never even thought of it. I just did it because I loved it.”

When he returned to Australia, he continued to paint in his spare time. He had no formal art training and no specific ideas about style. “I just painted and drew.”

Gradually he met other artists and started making art-world connections, among them Charles Blackman and John and Sunday Reed, and attracting critical attention. His first one-man show was in Melbourne in 1956, and only two people showed up: “One was Arthur Boyd and the other was John Perceval, who wouldn’t go anywhere without his dog,’’ he recalls. “I was very lucky — the dog liked me.”

Then came the show that still ranks as one of the more rancorous episodes in Australian art history.

“AS Antipodeans we accept the image as representing some form of acceptance of — an involvement in — life. For the image has always been concerned with life, whether of the flesh or of the spirit. Art cannot live much longer feeding upon the disillusions of the generation of 1914. Today dada is as dead as the dodo and it is time we buried this antique hobby horse of our fathers.”

Led by writer Bernard Smith, the 1959 Melbourne exhibition The Antipodeans shaped itself in deliberate opposition to abstraction. Of the seven artists taking part — the others were Arthur and David Boyd, John Brack, Clifton Pugh, Blackman and Perceval — Dickerson was the only one from Sydney.

It was a divisive show, by design, although the Antipodeans never showed again as a group. Looking back, Dickerson says he agreed to take part only because he thought the exhibition was going to be shown overseas. He also distances himself from the famous Antipodean Manifesto written by Smith and signed by the artists involved.

“I didn’t give a damn about the people painting abstracts. Good luck to them. They were all my friends anyway,’’ he says now.

“They switched to abstract and said, ‘Why aren’t you doing abstracts?’ I said I can’t work out what you can get out of it, there’s nothing happening, just a lot of colour, I might as well throw paint at the wall.”

The way Dickerson tells it, the figurative crusade against abstraction went only so far: “When the show was finished, we went back to have a little drink with the bloke who started the whole thing. Lo and behold the wall was covered with abstract paintings. I thought, ‘This is ridiculous.’ I got up and walked out.”

SIXTEEN years ago, keen to escape the bustle of the city, where a short walk to the TAB was beginning to take forever because of the number of people to chat to along the way, Dickerson bought a 90ha property two hours south of Sydney. He wasn’t especially familiar with the area, although he used to spend time at the nearby Lake Illawarra during the Depression, prawning and fishing. The relocation was a quest for space and quiet, but it was also about racing: the man who trained his horses lived in the area and wanted a track to exercise them.

He named the property Turpentine Park, a reference to the painting and the trees scattered throughout. These days it’s a busy thoroughbred stud with about 40 horses, a handful of which are owned by the family. The artist has an affection for horseracing but that doesn’t mean he wants to spend much time in the company of the animals: “I wouldn’t go near a horse. You don’t know what they’re going to do.”

Dickerson lives there with his third wife, Jennifer, a writer, poet, journalist and former art valuer. The pair have been together for more than 40 years, and have lived variously in Queensland, where Dickerson used to play chess with Ian Fairweather on Bribie Island, and Sydney. When they moved to Cambewarra, they initially lived above the stables while the house and studio were being built, and Dickerson regularly drove across to Bundanon, Arthur Boyd’s place 30 minutes away, to work.

“I did a lot of work over the first 10 years,’’ he says. “A heck of a lot. It’s quite good.”

While some of his contemporaries were quick to travel abroad in the 60s, eager to connect with some of the energy of London or New York, Dickerson focused his energies at home, where he had a growing family and work commitments. He was included in the 1961 Whitechapel show of Australian art in London, but his first trip to Europe wasn’t until 1972.

Dickerson had also been drinking heavily for some time before he met Jennifer. Soon he found a way to bring the “poison” of alcohol under control. “If I was still drinking I’d be dead a long time ago,” he says.

His is a formidable family: he has nine children, 20 grandchildren, 14 great-grandchildren and one great-great-grandchild. The family is closely involved in his affairs: his youngest child, Sam, manages the horse business and runs the Dickerson Gallery in Sydney. A stepson, Stephen Nall, ran the Dickerson Gallery in Melbourne until it closed in 2010, and now works as a lawyer and art consultant.

In 1994, Jennifer Dickerson published Robert Dickerson: Against the Tide, a handsome book that details his life and art. At the back of the book she has printed a series of questions and answers in which she asks her husband about his methods, the influence of others, art criticism and so on. She asks him about the people he paints, referring to one critic who described them as wearing “an expression of apprehension of impending doom”.

“Everyone is apprehensive,” he responds. “Look at people in the street, in traffic.”

Dickerson’s recognisable markings, those angular faces and scenes of stark isolation, have been consistent through the years. Familiarity, though, can pose its own challenge. In 2010, Victorian Supreme Court judge Peter Vickery ordered the destruction of three paintings wrongly attributed to Dickerson and Blackman. Vickery ruled the paintings — two by Blackman and one by Dickerson — were “fakes masquerading as the genuine article”. “What is more,” the judge continued, “they were deliberately contrived to deceive unsuspecting members of the public in this manner. The false signatures drawn on each of the works could have had no other purpose.”

Nall gave evidence to the court about the fakes and about his stepfather’s work. Blackman suffers from Korsakoff’s syndrome, an alcoholic dementia, and the judge accepted he was unfit to give evidence.

Dickerson spent a few hours on the stand, an ordeal he describes as “pretty terrible”. He recalls: “You felt like punching the bloke in the face down there.”

Dickerson was also insulted by the quality of the fake: “Nothing like mine. I said it was ridiculous. They kept on grinding away, trying to make me look an idiot, make a mistake. But I didn’t make a mistake.”

Vickery’s judgment gives a sense of how it all went down in court, when Dickerson was giving evidence and describing the offending work as disgusting.

Why did you think it was disgusting? “Because it’s very bad work, it’s a very commercial little study.”

What about it conveyed to you that it was a work of that kind? “Well, the neck is out of proportion.”

Just take it slowly in steps, please. “Its neck is out of proportion, its eyes are wrong, the hair is wrong and the shape generally of the face is wrong.”

Later, during cross-examination, he discusses the “one big alteration (that) turns what should have been a good drawing into a bloody awful one”.

What’s the clumsy line? “Everything about it, the drawing itself is clumsy.”

The dodgy works were later burned in the back yard of the Dickerson gallery in Sydney. Blackman and Dickerson have had a fractious relationship through the years, but they came together for this occasion. Even though, as Dickerson tells it, it almost left the frail Blackman worse for wear: “Charlie came around and we burnt them all together,’’ he says, “and Charlie nearly caught on fire.”

IN 2010, the Dickerson family donated several works to the National Gallery of Australia. The NGA is one of many organisations he has helped out through the years, with donations to the likes of Opera Australia, the Australian Ballet, Sydney Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Newcastle Hospital. He donated 10 paintings to the NGA. But why give them to Canberra and not the Art Gallery of NSW? After all, Dickerson has spent much of his life in the state.

The question touches a nerve. “The Sydney gallery is not very friendly with me,” he says quietly. Jennifer Dickerson says the NGA was chosen because the gallery had always shown an interest in her husband’s work. She is adamant Dickerson should have had a retrospective by now. It’s a similar complaint to one made by Blackman’s family in recent years, and comes in response to what she sees as a preference by the gallery for Brett Whiteley and other higher-profile artists.

“I personally think they should have had a retrospective by now because he’s a NSW-born painter,’’ she says. “But there’s never been any approach to us, any interest in what we’ve got.”

In the meantime, the new show looms in Brisbane, at the Philip Bacon Gallery.

There are 33 works in total, with the oldest dating back to 1965, Boy Playing in the Street. Most of the show focuses on more recent years, from the late 1980s onwards, and there are three pictures from this year: The Mounting Yard, a racing scene, naturally; Seated Geisha and Girl with Flowers. “I haven’t changed very much in the way I paint,” Dickerson says. “I’m still painting the same way as when I started.”

There have been plenty of accolades along the way, of course. Last year, he became an officer in the general division of the Order of Australia, in recognition of his contributions in art and philanthropy. The citation read: “For distinguished service to the visual arts as a figurative painter, and to the community through support for a range of cultural, medical research and social welfare organisations.”

If Dickerson feels at all emotional about a show that coincides with his 90th birthday, then he hides it well. The exhibition gives him an opportunity to see whether these works have stood the test of time, he says, and he’s satisfied that most have done so.

“It gives me a look at things that I’ve done. That’s about all.’’ He pauses, and reaches for a tissue. “I can’t think of anything else.”

Robert Dickerson: Paintings and Pastels 1965-2014 at Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, from July 8 to August 2.