Rick Gekoski’s debut novel Darke: the name says it all

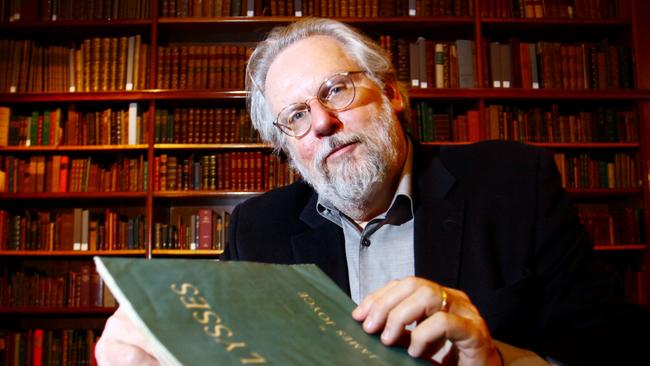

At 72, Rick Gekoski, who has handled a signed, first edition of Joyce’s Ulysses, has written his first novel.

Rick Gekoski, American-born, England-domiciled, an entertaining panellist at the Sydney Writers Festival a few years back, is an eminent rare book dealer, a former literature academic — he taught at Warwick University, with Germaine Greer — a publisher, bibliographer, broadcaster and now, at 72, a first-time novelist. As Edgar says to Lear, “Ripeness is all.” His BBC radio series Rare Books, Rare People was saluted by Britain’s The Daily Telegraph as “one of the gems of radio”.

Gekoski’s entertaining and erudite elucubrations have been collected in Tolkien’s Gown (2005), billedas “twenty great works of literature as texts and objects”, and Nabokov’s Butterfly: And Other Stories of Great Authors and Rare Books (2004), in which the title essay relates to purchasing from Graham Greene his first edition of Lolita, with Nabokov’s signature drawing of a butterfly inside, and the next day selling it to Elton John’s lyricist at a €10,000 profit. Or so the story goes. The Tatler has dubbed Gekoski “the Bill Bryson of the book world”, which we are to assume is intended as a compliment.

And so to Darke, which is both the title of Gekoski’s maiden novel and the name of his narrating misanthrope. It seems a pity that Moliere got in first to claim that title. Gekoski would have known that, both he and his novel being so literary and learned, if lightly so. The novel is larded with allusions, overt and covert, to “dark” and “darkness”, from Milton to TS Eliot, from Corinthians to Dylan Thomas, though St John of the Cross (‘‘en una noche oscura’’) appears to have been overlooked. Darke is truly an instance of nomen est omen, as those old Romans used proverbially to say.

The novel begins dramatically and all but climactically, with Dr James Darke immuring himself in his London house, having engaged a handyman to fulfil five requirements: remove a brass letter box from his “handsome Georgian door”, fill in resultant hole, prep and paint in Farrow and Ball Pitch Black Gloss; install a “melodious, inoffensive” doorbell that rings once only; install a Dial 6mm-x-200-Degree-Brass-Door-Viewer-Peephole-with-Cover-and-Glass-Lens; install a new keyhole and change lock; remove the brass door-knocker, and make good. These tasks successfully completed, this Darke Englishman’s home must be his castle.

Darke is divided into three parts, of which the first, with its unbridled misanthropism, is the best.

There is a tradition in the English novel of the previous century, usually penned by men, wherein the central character, while scabrous and misogynistic, seems against all odds to emerge as honourable and estimable. Consider Anthony Burgess’s Enderby novels, and the works of Amis pere and fils, especially the former’s One Fat Englishman and his Booker Prize-winning The Old Devils, thought by his son to bear comparison with any English novel of the 20th century.

In his acknowledgments, Gekoski salutes his wife, Belinda, who initially did not like Darke “one little bit”. A tractable husband, Gekoski rewrote part one, in which Darke is “considerably toned down from his first and darkest incarnations, in which his disgust with himself and his fellow humans was more pronounced”. Would he have done better to have observed Oscar Wilde’s advice, “Nothing succeeds like excess”?

Well, Darke is a triumph of the immoderate as it stands, throughout part one. Parts two and three are, in effect, an explanation of the Darke-ness of the first section. They are a wrenching account of the death from cancer of Darke’s wife, Susan, and her refusal to “go gentle into that good night”. Then of Darke’s grief, which his obnoxious daughter Lucy refuses to acknowledge.

Then there is Darke’s grandson Rudy, whose company he “enjoys in small doses”, thinking his reading habits subverted by his social-worker father. Why “Rudy”? Here’s a theory. This is an allusive, literary novel. Gekoski as dealer has handled a signed first edition of Joyce’s Ulysses valued at $450,000. Not something you would forget. Consider the final lines of the Joyce’s Circe chapter, in which Leopold Bloom encounters the ghost of his dead son, a pere et fils to outshine the Amises.

“BLOOM (Wonderstruck, calls inaudibly) Rudy!

“RUDY. (Gazes unseeing into Bloom’s eyes and goes on reading, kissing, smiling. He has a delicate mauve face. On his suit he has diamond and ruby buttons. In his free left hand he holds a slim ivory cane with a violet bowknot. A white lambkin peeps out of his waistcoat pocket.)”

There are thoughts that lie too deep for tears, as Wordsworth bore witness. Darke in his misanthropy lacks the lachrymose, perhaps not shedding tears even for Suzy, who would not have approved.

Don Anderson taught American literature at the University of Sydney for 30 years.

Darke

By Rick Gekoski

Allen & Unwin, 299pp, $32.99