Richard Ford reflects on his parents in Between Them

This is a deeply beautiful book by a master craftsman that will remind you of your own parents.

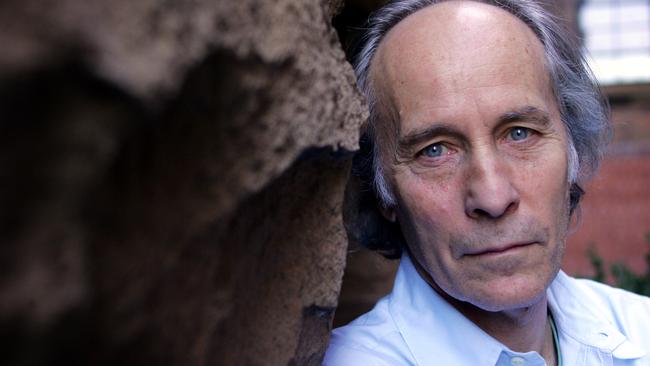

Richard Ford is one of the great American realists. For 30 years he has been producing fiction that comes with a shock of recognition. He presents us with the faces and voices, the landscapes and incidentals of contemporary America while also reconfiguring them into patterns that delight the mind with their images and their music.

Sometimes he has looked like a natural-born heir of Ernest Hemingway with a taciturn prose and a vision of what is rough as well as what is decent.

Sometimes, as in the Frank Bascombe novels that begin with The Sportswriter (1986), there is more fancy, even dandyish prose, as well as a sensibility that is literary and sidelong and can seem like some kind of persona of the author.

Now he has written a memoir of his parents, the stories of his mother and father, penned 30 years apart. It is a remarkable book, moving and grave. It is also sort of what Harold Bloom likes to call a wisdom book. It hits with the power of a not-quite-glimpsed truth.

Here he is on what could be called his father’s lack of inner resources, though that’s not quite the habit of mind Ford exhibits:

I do not know about my father’s faith — if he had any. He might have said he did — after his heart attack — but he did not practise one, not as long as I knew him. I knew he didn’t take pleasure in books — where he could’ve found what we all find if we don’t have faith: testimony that there is an alternate way to think about life, different from the ways we’re naturally equipped. Seeking imaginative alternatives would not have been his habit.

This is beautifully put and it’s a reminder of how much the easy aestheticism of educated people does constitute a sort of implicit spirituality, and an advantage that different but in no way inferior people do not have.

The no way inferior is important to Ford. This first part of Between Them, about his father, was written 30 years after the second part, about his mother, occasioned by her death in 1981. It is a tremendous homage to the mute, inglorious reality of the novelist’s father.

What was it James Joyce wrote in that fragile, delicate poem about the man he immortalised as Simon Dedalus? “O father forsaken / Forgive your son!”

That is, of course, the utterance of a son who became a father. It has as its occasion the death of Joyce’s father and the birth of his grandson. And so its Latin title Ecce Puer (Behold the Boy), which echoes Pilate’s words to the crowd, points both ways. There is terrible poignancy in indicating how a baby will eventually suffer his equivalences to crucifixion and how an old dead dad was once somebody’s infant.

Isn’t there the ghost of a memory, long ago, of Ford saying that sometimes parents don’t have that much significance for a writer? This memoir belies and defies that with a vengeance even though Ford’s portrait of his father, Preston Ford, makes no attempt to glamorise or transfigure.

Preston’s father committed suicide. Preston sold starch for a living, in the American south, travelling hither and yon for a long time, often apart from young Richard, then not, after he had a heart attack as a middle-aged man.

It’s a portrait of an ordinary man that refuses the implication of its own adjective.

Ford was born long after his parents would have given up on the idea of having kids. His arrival, 15 years into their marriage, must have complicated lives where his parents would have been forever in each other’s pockets, sipping and sucking at life as if it were so much bourbon.

One of the notable things about this book is how Ford makes his father’s limitations look like the insignia of his individuality.

And then there are the dreams: the country boy who falls in love with suburbia, the man who would like to be able to fish, the fantasies about new cars. He loses it with young Richard over a Christmas tree, he runs to fat, he goes bald, and there’s the innocence of his smile, how he was felled by a heart attack, how he lived for the glow of his wife’s company, the fight they had, drinking, at that particular restaurant, how their son lay between them and soaked up their love and the heartache of their loss.

Though Ford never cried for his father when he died, as he recalls in his afterword, this first, belated part of Between Them is there by way of elegy and apologia, a lament of a Makar for a man who was, and who seemed, just a man, as if that limited him.

There is plenty of detail about the two sides of the family, skeletal details emphasising differences that have the raw gust of poignancy because a story that exists as an outline round which a great writer muses is bound to seem full of gaps and losses.

Of course loss is the subject of Ford’s story; loss and love. The memoir of his mother is the complement of the story of his father, though you can see why it sprang on to the page when Ford was a lot younger. Here he is on his mother’s time with the nuns and its aftermath:

St Anne’s cast both a light and a shadow into her later life. In her heart of hearts — as her Irish mother-in-law darkly suspected — my mother was a Secret Catholic which meant (to her) that she was a forgiver. A respecter of rituals and protocols. Reverent about the trappings of faith and inner disciplines, although she was uncertain about God. All I’ve ever thought about Catholics, good and not good — I first thought because of my mother, who was never one, but who lived among them at an impressionable age and liked what she learned and liked who taught her.

The sheer ease of this kind of writing is wonderful. Ford’s mother looked like him, she had his brow, his stunning bright blue eyes, she seems to have had his snap and bite. He recalls a day in a cafeteria where she pointed out one of the other customers. “That’s Eudora Welty. She’s a writer.’’ Ford is not sure if it was her or not. “My mother may have wanted it to be Eudora Welty for reasons of her own. Possibly this event could seem significant now, in view of my life to come. But it didn’t, then. I was only eight or nine. To me, it was just another piece in a life of pieces.”

He’s as good as any writer alive at the pieces. The burden of this book, in which his parents exist in the medium of the writer’s love, is that his mother never got over his father’s death, from a second heart attack, when Richard was 16. “When my father died, of course, everything changed — many things, it’s odd to say, for the better, where I was concerned. But not for the better where my mother was concerned. Nothing for her would be quite good again after February 20th, 1960.’’

The second part of Between Them is one of the great homages a son has written to a mother. It is a man’s lamentation and love for a woman, though not at all Oedipal. In fact if you were to talk about this book in psychological terms — and there’s no need because Ford’s story here is its own analysis — you would say its dominant impulse is to restore the image of the father, not to get rid of him.

But there is a surging and stark power of truth, a sense of irreducible tragedy, in the way Ford tells his dying mother of course she should come live with him and his wife, and she is filled with relief, and then he qualifies it as to timing, and then she dies.

This is a deeply beautiful book by a master craftsman who is disdaining of the tricks of his craft — or all appearances of them. It will remind you of your own parents and those you have loved now gone.

It has, if you like, just a touch of that uncanny thing you get in late Tolstoy stories, of a truth beyond words that makes words work without surrendering to them. But this is, in the end, a memoir beyond praise.

Peter Craven is a literary critic.

Between Them: Remembering My Parents

By Richard Ford

Bloomsbury, 192pp, $18.99 (HB)