Richard Alston is reading all 318 Booker prize books

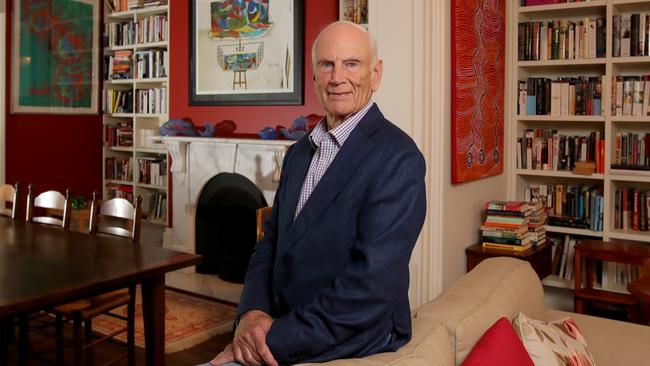

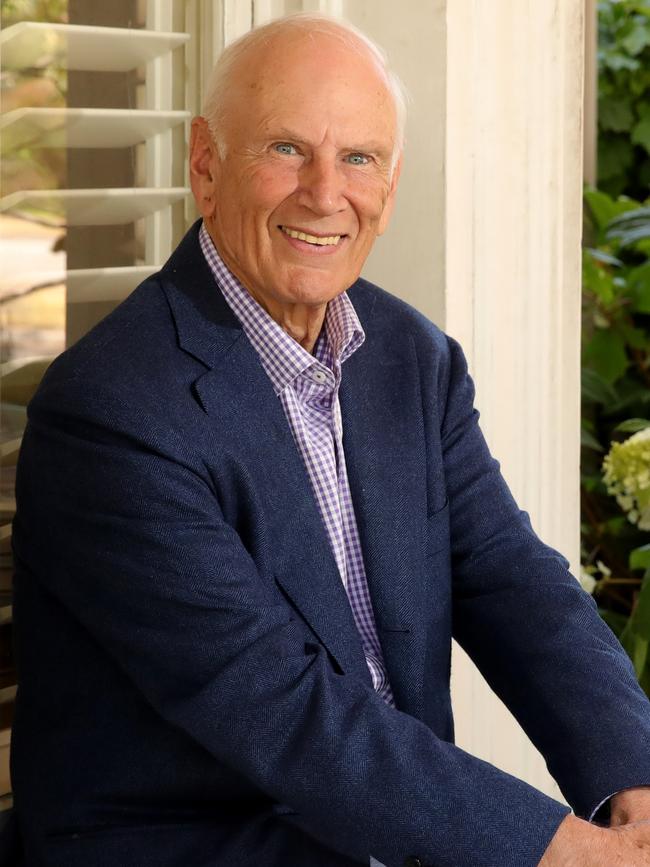

Former arts minister Richard Alston has amassed an incredible collection, and says the relentless pursuit of novelty and diversity has meant that seriously good writers have missed out.

I have always enjoyed reading good books. Growing up in the 1950s, before television took over our lives, I read many of the classics and have kept up the pace ever since. It should therefore not be surprising that I eventually became the owner of what the experts regard as the world’s largest collection in private hands of UK-published, author-signed, first editions of all the books ever short-listed for the Booker Prize – to date numbering 318.

The Booker Prize, first awarded in 1969, is one of the world’s eminent literary awards, open to any author whose book is published in the UK and Ireland.

The prize ceremony is normally held in London, as I discovered when I got to London as High Commissioner in 2005. I also realised that I had read more than half of the Booker shortlist, and it seemed worth trying to finish – and perhaps to buy – them all.

I began building up a network of booksellers and other Booker aficionados, who helped me in my quest. By the time I left the UK in early 2008 my search was more than 80 per cent complete. Chasing the remainder proved to be quite difficult. Six of the books I needed to find were by women. Even in the late 20th century there was a clear imbalance of female authors on the shortlist, and it seems that they didn’t sign as many of their books, let alone go on as many author’s tours, writers’ festivals or book fairs. Since its inception, the male-female ratio for Booker winners and those on the shortlist has been around 2:1, although it is gradually rebalancing.

It is often difficult to predict the winner, making the prize somewhat of a bookies’ nightmare, with established authors often failing to make the shortlist. I remember when meeting Graham Swift, who had won the Booker Prize with Last Orders, I had to tell him that I thought his earlier work, Waterland, was a better book, to which he sheepishly replied: “A lot of people tell me that”.

This suggests an element of catch-up by the judges. They can also be ahead of the curve: Ian McEwan won with Amsterdam, a run-of-the- mill work, while his later book, Atonement, which didn’t win, was praised by critics, and won many other awards.

The formal announcement of the Booker is an elegant, black-tie affair at the Guildhall, an imposing medieval hall, with stained glass windows. It was always a pleasure to attend.

On one occasion, I had sat next to one of the judges, a brilliant literary biographer, who told me that they had to read something like 150 entries in about four months, plus re-reading the six short-listed books. When I expressed amazement at the rigour of the process, she looked at me conspiratorially and said: “The secret is, if a book isn’t working for you after 70 pages, throw it away”.

So, what have I learnt, from reading the Booker shortlist? I think I can confidently say that the relentless pursuit of novelty and diversity has meant that seriously good writers such as William Boyd and Sebastian Faulks have missed out (Faulks’s Birdsong wasn’t even short-listed).

Likewise, outstanding writers like Julian Barnes and Howard Jacobson had to wait patiently for ultimate recognition, while others have come from nowhere to take the prize.

In 2022, Sri Lanka’s Shehan Karunatilaka was a well-qualified winner, even though his only other published work was rated as “the second greatest cricket book of all time” by Wisden. Of the other short-listed books three were little more than novellas. I’m pleased to be able to say that, apart from Hilary Mantel of Wolf Hall fame, only two other authors have won twice: Peter Carey, an expat Australian who resides in New York and JM Coetzee, an expat South African who resides in Australia. Three other Australians have been winners.

Collecting the books on the shortlist requires some understanding of the bookseller’s trade. As I came to understand things, it’s harder to get signed copies of books by first-time writers, and that’s because, when authors are first starting out, publishers cannot be confident of large sales, and therefore can only afford small print runs.

When only a small number of signed books are available, it is emphatically a sellers’ market, particularly as there are very few booksellers who specialise in Bookers.

The vendor knows the scarcity value of a particular book and is therefore able to dictate the price.

Another point that I think is interesting: the arrival on the Booker scene of previously-unheralded writers may well be due to new technologies that have facilitated the emergence of very small publishing houses, which, almost by definition, do not represent established authors.

At the same time, I would argue that the Booker in recent years has become more populist in approach, more ready to accommodate fads, such as short-listing a poem and a book with no full stops. Yet, despite and maybe because of all its foibles, it still retains a magnetic attraction for serious book lovers, including me.

Richard Alston is Australia’s longest serving Arts Minister and a lifelong book lover