Rewriting history books: King Henry V, we hardly knew you

Shakespeare described King Henry V as a lightweight, but the real King was tougher, says Dan Jones.

A decrepit ruler too stubborn to go. Aides and counsellors aware of his diminished faculties but too timid to speak up. Six centuries before Joe Biden, it was England’s King Henry IV who would not budge.

Too frail to stand up, let alone mount a horse, the king still harboured delusions about being able to lead his army into battle against the French. Eleven years earlier, Henry had seized the crown from his own cousin, Richard II, before starving him to death in Pontefract Castle. This time the boot was on the other foot. The pretender was his eldest son, Henry Prince of Wales. Unlike Joe, Henry stuck it out, lingering on the throne for another two years before his son inherited the English crown as King Henry V.

If we know or care much about King Henry V today, it is largely Shakespeare’s doing. In the bard’s version of his life, young Henry is Hal – a “lightweight, flippant, sensuous gadfly” in Dan Jones’ words, “a lover of women and a charmer of men” who “plays the fool for so long that he almost becomes the fool, until, at the moment of his father’s death, he realises he can cavort around no more”.

Jones, Britain’s best-selling medieval historian, is having none of it, dismissing Shakespeare’s engagingly human depiction of Hal/Henry as a “cartoon history” of Henry’s life and reign. The truth, Jones tells us, is that Henry enjoyed a fuller apprenticeship to kingship than any English monarch since Edward I, more than a century earlier. He understood that the people required a grave, pious, just and sober king, so that is what he gave them. On the night his father died, Henry spent time praying with and confessing his sins to a Westminster hermit. Thereafter he was rarely seen without an entourage of priests, preachers and “professional praying men”.

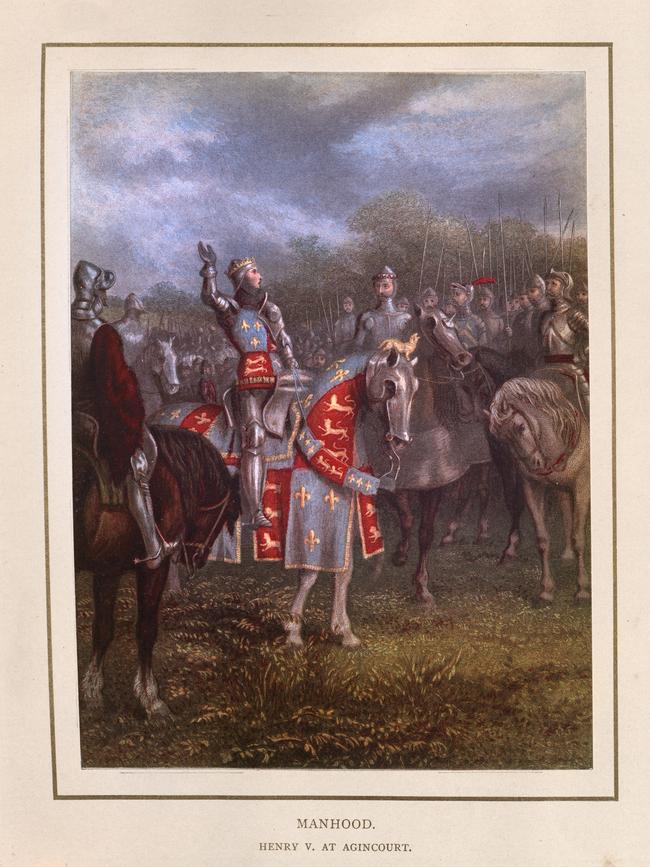

But it is not for nothing that history has cast Henry V as England’s warrior king. He was just 16 when he was hit in the face by an arrow shot from a longbow at the Battle of Shrewsbury, where forces led by his father defeated a rebel army. The greater part of Henry’s nine-year reign was spent outside his own kingdom, campaigning in France to assert his dynastic claim to the French throne. His triumph at the Battle of Agincourt was arguably Britain’s most famous military victory of all.

Henry could be spectacularly ruthless towards his enemies. Like most medieval battles, Agincourt ended with large numbers of prisoners held for ransom. When another French army was rumoured to be returning to the battlefield, Henry gave orders for all but two of his most valuable prisoners to be hacked to death on the spot. The order so affronted his own men that Henry was forced to send in a death squad of 200 archers to get the job done. “This pitiless order to slit the throats and beat in the skulls of vulnerable men will in time be counted as a great stain on Henry’s character,” Jones writes, “a prized piece of evidence for those who would cast him as a blinkered, heedless warmonger bereft of conscience and ambivalent to the values of chivalry”.

Jones, author of brilliantly crafted and politically astute histories of the Plantagenets, the Wars of the Roses and the Crusades, is not among them. Nor, interestingly, were Henry’s French contemporaries, who lamented the great number of French dead (more than 3000 knights and squires, including three dukes and five counts, and the same again in “ordinary men”) but “[did] not castigate Henry for his inhumanity”, blaming the massacre instead on “wretched” French soldiers whose apparent return to the battlefield prompted Henry’s order to kill the prisoners.

To Jones, King Henry V was a ruler of substance, an inspired (and sometimes lucky) military commander who also understood the need for just and effective government; he clamped down on unlicensed doctors, for example, and ensured that Oxford students running amok in nearby towns and villages could be charged with outlawry.

At the same time, he was a canny political operator who understood that style mattered, as well as substance, and was able to convince his contemporaries that he “had somehow secured the full approval of God”. Henry, Jones writes, “had a reputation for being austere to the point of dessication, yet he was also theatrical and astonishingly adept at the art of public spectacle”. (Believe it or not, he was also a talented harpist who took time off from fighting the French to pay £8 13s for a pair of harps for he and his wife to play together.)

In his introduction, Jones writes that this is a book he has been waiting to write for some time, having deliberately left a “Henry V-shaped gap” between his books on the Plantagenets and the Wars of the Roses. His approach is unusual in devoting exactly half its length to the years before Henry was crowned. This pays rich dividends in helping to unravel the seeming contradictions in Henry’s behaviour as king.

More unconventional, for a narrative history, is that Jones opted to write in the present tense. He chose this approach, he tells us, in order to “animate” Henry, to put us “on the cusp of the next crisis … jolted out of our comfortable place in the distant future” and forced to “wrestle with the medieval world in real time”.

The present tense can be grammatically awkward when narrating the remote past and Jones’ use of it felt a bit laboured at times. I’d be surprised if readers find his other books any less immersive for being written in the past tense. As for our place in the distant future being “comfortable”, future historians will have something to say about that.

Tom Gilling is a writer and critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout