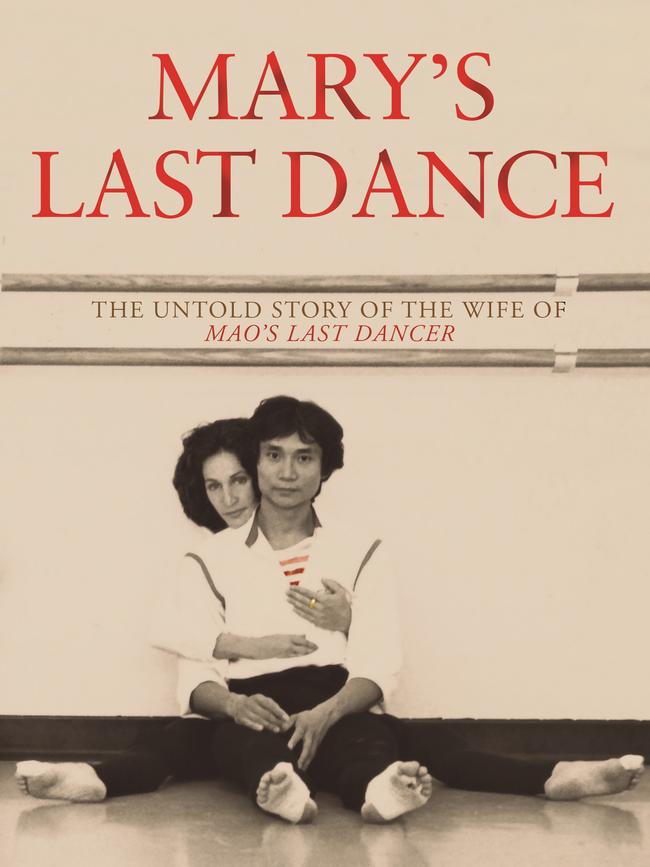

Review, Mary’s Last Dance: The Untold Story of the Wife of Mao’s Last Dancer

Mary McKendry, wife of Mao’s Last Dancer, knew she had to retire when she discovered her 18-month-old daughter was deaf.

At age eight, Mary McKendry took her first ballet lessons at a small ballet studio in Rockhampton, central Queensland. A lively tomboy with a wild bird’s nest of hair, raised in a large, boisterous Catholic family, she was, as she would later write, “the most unlikely candidate to be a ballerina”.

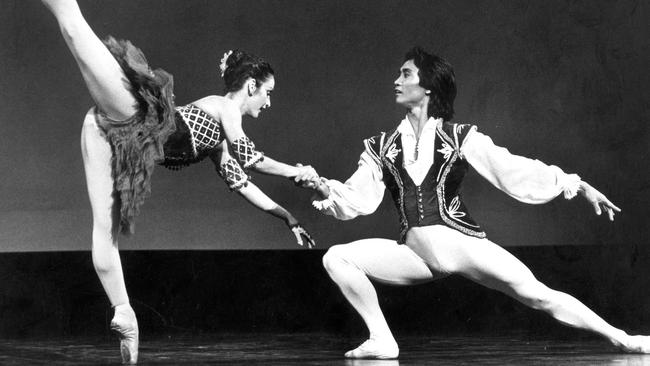

At 16, however, the country girl with the huge leaps and raw talent would successfully audition for the Royal Ballet School and head to London where she would build a stellar dance career at the London Festival Ballet, dancing alongside Rudolph Nureyev and touring the world as principal dancer before joining the Houston Ballet under acclaimed director Ben Stevenson.

There, she meets a young Chinese dancer, Li Cunxin. The chemistry is instant, and the pair would go on to dazzle the international dance world as partners on and off stage.

In 2003, Li’s memoir, Mao’s Last Dancer, telling the extraordinary story of his rise from poverty in post-Cultural Revolution China, his defection to the US, and evolution into one of the world’s most accomplished ballet stars, becomes a worldwide bestseller and then a blockbuster film.

Now, in what Li, in the foreword, bills as a sequel and companion piece to Mao’s Last Dancer, his wife has penned her own memoir. Mary’s Last Dance is a different kind of work: not a dance memoir as such, though there is plenty of rich detail of her years in dance and encounters with the likes of Fonteyn, Markova, Sibley and Nureyev, but a journey that explores everything from the perils and joys of parenting to the world of deaf politics to sacrificing ambition and career to mother-daughter relationships, centred around her and Li’s rollercoaster journey in raising a child with a disability, their daughter Sophie.

In the early years of their life in Houston, Li is the first to notice something is amiss, McKendry recounts. Sophie doesn’t flinch at loud noises, he tells her. She dismisses his concerns. Their daughter is meeting all her milestones, and if she is a little slow to start talking, hadn’t all the doctors attributed her delayed language acquisition to living in a bilingual household? But the seeds of doubt are planted; Sophie is taken for a hearing test. The diagnosis is devastating – their 18-month-old daughter is profoundly deaf.

For Li and McKendry, there is a special cruelty to the diagnosis. Both onstage and off, their lives had been shaped and defined by music: dancing for the first time together at the Houston Ballet to Solveig’s Song in Peer Gynt; dancing for the final time at the company in an emotional performance of The Nutcracker in 1991. Music was the constant soundtrack to a life dedicated to movement. And now, their child would forever remain closed off to all this beauty.

Performing with Li in Christopher Bruce’s Ghost Dances shortly afterwards, McKendry is paralysed by grief. “The end of the piece has the mother leading the whole village, rocking forwards and backwards in unison. This repetitive sequence evokes a powerful feeling of oneness. In this moment, a thought occurred to me that gripped my heart like ice. Oh my god, Sophie will never hear this sound, this hauntingly beautiful Chilean music or any music – ever.

“The mother I thought I was and the daughter I thought I had were taken away from me … now we were trying to imagine a completely different future for ourselves. A musical world with dancing and laughter was no more.”

For McKendry, an even more profound bifurcation lies ahead: she knows her life as a dancer is over. If there is any chance of Sophie ever learning to speak, they are told by a speech therapist, she would need the devoted attention and full-time care of a parent at home. For McKendry, there is no hesitation: she will retire.

A devastated Li offers to give up his dance career instead, but his English and general pronunciation is still a work in progress. With that, a door is closed on a lifetime of sacrifice and hard work, applause and accolades. McKendry has a new goal: “I want to hear her voice.”

Before the curtain falls, there is one last dance with Li in The Nutcracker at Houston Ballet. The performance, raw and emotionally resonant, is a triumph. “With Li by my side I was able to let my emotions fly … I felt totally free – soaring above the score one last time.”

McKendry recalibrates her life, the daily effort of the rehearsal studio and the discipline of the barre now channelled into teaching Sophie to speak. All day, from morning to dusk, she talks to Sophie, an endless stream of words that she prays will find a listener.

Li explores qi gong, Chinese acupuncture, takes Sophie to see a famous healer in the Laoshan Mountains in Qingdao. All to no avail; Sophie remains locked in her bubble of silence.

Life at home, too, becomes muted, McKendry writes. “Up until Sophie’s diagnosis, our lives had been all about music and the two languages. Now, we packed away music and other noises from the house – stereo, radio and television – to create a quiet environment to best enable Sophie to hear.”

More blows follow: on the advice of speech therapists, Li’s parents Niang and Dia return to China; two languages could hamper or delay her speech, they are told. For Li, the loss of his dream of hearing Sophie speaking Chinese as a conduit to his family and culture is devastating.

The next few years are marked by small wins but progress is slow and painful. Then comes a breakthrough: Sophie undergoes surgery for a cochlear implant, the revolutionary hearing device invented by Australian scientist Professor Graeme Clark. A switch is suddenly flipped, McKendry writes. “Within six months, Sophie was babbling like crazy.”

Returning to Australia, a new life is painstakingly built. Year by year, despite setback after setback, McKendry’s single-minded effort reaps small miracles: at 10, Sophie is chosen to make a commemorative presentation to Chinese President Jiang Zemin when he visits the Bionic Ear Institute; learns to play the cello in the school orchestra, speaks in St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne, plays the piano before an audience of 500 in Houston, learns to speak Mandarin and then Spanish.

“Originally, I had desperately wanted my daughter to say one word,” McKendry writes. “Then I’d wished for a paragraph, then a whole conversation.” Now, the little girl born into silence had found her voice, was living a life of music and movement, just as her parents had. For Li and McKendry, it has been the ultimate reward; nothing in their stellar dance careers has come close. “Family was what it was all about for us. It always was and it always will be.”

Mary’s Last Dance: The Untold Story of the Wife of Mao’s Last Dancer by Mary Li with foreword by Li Cunxin (Viking, 480pp, $34.95).

Sharon Verghis is a journalist and writer.