Reason & Lovelessness: Essays, Encounters, Reviews 1980-2017, by Barry Hill

Literature meets lived experience in Barry Hill’swide-ranging essays.

Some literary careers run the risk of obscurity not because they are slight but because their scale or ambition exceeds the usual parameters. Another potential for invisibility awaits authors who wrong-foot audiences by shifting theme or genre with each new work. There are others still who perplex by choosing subjects at odds with public appetite or contemporary mood: writing of religion during a secular era, say, or of workers’ rights during a neoliberal moment, or of art in an age of empty spectacle.

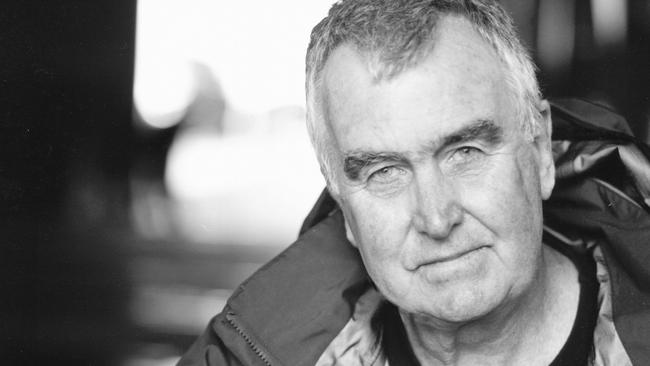

Which brings us to Barry Hill, journalist, biographer, poet, novelist, critic, scholar, writer of place and anthropologist of the interzone between East and West, Antipodes and Old World, and, most searchingly, white and black domains within Australia. His major projects — of which the best known is his Broken Song, an immense celebration and critique of TGH Strehlow’s little-known masterpiece of comparative literature, Songs of Central Australia — have taken up to a decade to research and write.

Likewise, he devoted years to a 700-page travelogue through Asia called Peacemongers, seeking to understand the suasive force of thinkers and activists such as Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi, and before that a book-length poem on the escaped convict William Buckley, who lived for decades in the early 1800s alongside the Wathaurung people of southern Victoria, occupied his attentions.

Earlier still, he wrote a nonfiction account of the 51-day sit-in during late 1979 involving Union Carbide workers at a plant in Melbourne’s Altona: an event in which the author’s union organiser father was a central figure.

The picture starts to form. As historian Tom Griffiths asks in his generous and admiring introduction to Hill’s collection Reason and Lovelessness: “How might we reach some holistic understanding of such a versatile and wideranging writer?”

On the basis of these essays — almost four decades’ worth of miniaturised, fractal pieces touching on all these larger projects and more — it is a case of playing the man, not the work.

For if there is one thing that yokes together such a disparate body of writing, it is Hill’s personality, a style deeply impressed on every line — not in the sense of codified literary affectation, rather a constancy in orientation towards the world: one that is warm, amused, impassioned, curious, questing, critical without being dismissive, gentle without forsaking rigorousness, equally occupied with the sensual world and the intellect with which that world is interrogated. It is the kind of braided thought that reflects “(in DH Lawrence’s words) a man in his wholeness wholly attending”.

A case in point is the opening essay, Dark Star, which is both an account of Hill’s slight but consequential acquaintance with the grande dame of 20th-century Ozlit, Christina Stead, and a personal investigation into the mysterious motions of the human heart. Hill writes with pith and insight concerning Stead’s return to Australia after decades in self-imposed exile in Europe, the US and Britain.

He locates her in the historical and social context of the early 1970s, and he ties the emotional and intellectual temper of her writings, which celebrated the transgressive nature of erotic passion and its tense relation with traditional marriage, to the changing mores of the country that had once again become her home.

So far, so insightful; Dark Star could have been a sturdy literary essay or a sliver of higher gossip. But these critical asides, which are inspired and shaped by a lunch in Canberra shared by the two in the early 80s, are interrupted by an account of the train journey from Sydney that Hill takes to attend the meal. It describes the affair that results from a chance meeting he has with an attractive Maori woman on the trip down.

The point is not the nakedness of Hill’s self-disclosure in these pages; it is that he blends autobiography with critical appraisal in such a way that each illuminates and enlivens the other. Stead was a powerful anatomist of human passion in her writings. But it took Hill’s admission of an extramarital fling — in the form of this posthumous letter to the senior novelist, written long after the events recounted — to locate the point where literature meets lived experience. The result is tragicomic melodrama with deadly serious intent.

Many of the pieces in the collection examine the point where two systems of thought, or two ways of being, similarly mingle. In those autobiographical pieces contained here, most moving among them Brecht’s Song, about Hill’s mother, the point of contrast lies between the quiet, modest household from which he emerged and the troubled domestic histories and future ambitions it was obliged to contain:

Home was where you tended the joys of life. Home was where your duties, those labours of love of me and my father, lay. They were nowhere else. Home was the garden of your loving, most flourishing self. Home was where you were, once upon a time, most free.

That he was set to escape this home, this family, exceed his class, pursue his passions without full care for the fixed proprieties of his parents’ stations, does not go unrecollected by Hill. Like other working-class boys made good, the very fact of the young writer’s difference as he matured tended to wound the plainer decencies of his mum and dad. And besides, the very virtues he ascribes to them here are shadowed. Honesty demands that neither Hill’s father nor mother emerge from their eulogies without flaw, and they are all the more human for it.

William Buckley, the “wild white man” who, in 1803, escaped his tiny penal camp in southern Victoria and made off for the bush, is another representative figure when it comes to crossing between two models of being.

For decades Buckley lived outside the bleakly punitive systems the Europeans had imported to Australia; he dwelled instead with the first peoples of the region, regarded by them as the risen spirit of a departed warrior of the tribe. He lost command of English and did not regain it until the area, bartered off the locals for tea and promises by John Batman, became once again the preserve of white men, and he felt moved to rejoin his kind.

In both his full-length poetry and shorter essay in these pages, Hill is concerned we do not make Buckley fit some made-to-measure literary template. He is not Robinson Crusoe — a mini-me imperialist with a nose for business and a Christian proselyte’s talent for instructing lesser races — but a more intriguing character still, at least in the author’s telling:

Buckley effectively chose to be and remain a native, an idea which involves us in an ethnographic leap in the imagination — a leap resisted by Defoe … Through thick and thin we are individuals defined by a different fabric of community. Try as we might to enter the essentials of Aboriginal society, it is not possible: linguistically, ethically, physically, metaphysically. It is all too different for the European Self to fully belong to.

“But Buckley,” continues the author, “travelled far enough towards Aboriginal culture to experience that difference, and there, in the firelight of the strangers, he made his home.” It is this field of experience, concludes Hill, “which pulses as an imaginative prospect, trying to reach, to touch, the unique qualities of Aboriginal being”.

There are many pleasures to be had and much to be learned from Hill’s essayistic excursions. Whether meeting the Dalai Lama in the Blue Mountains or railing against the dumbing-down of the ABC, hymning the joys of John Berger’s art criticism or the unblinking gaze of painter Lucian Freud, Hill is a cant-free figure whose prose compass trembles between Lawrentian expansiveness and no-nonsense laconicism.

But it is in the pieces dealing with Aboriginal Australia that the author is most in command of his material. Hill spent years travelling through the living heart of the continent, reading the explorers, naturalists, outback crackpots, Lutheran missionaries and racist anthropologists who are the only lenses we have through which to view early contact between white and black worlds. But he has also read the living poems of the first peoples of Central Australia and in his writing he has sought to correct some of the fantasy and supposition that clings to works such as Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines.

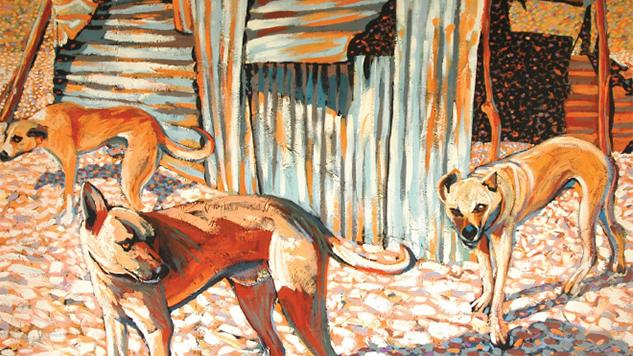

Whether in his clear-eyed reverence for the work of Alice Springs-based artist Rod Moss, whose painting of dingoes adorns the collection’s cover, or his divided respect for Theodor Strehlow, the man who produced the signal work of cross-cultural understanding between Europeans and indigenous Australians while gloomily presuming the latter’s terminal decline, Hill never fails to hew to the principle of full engagement with the Other.

This engagement, we come to realise, is work of imagination as much as morality, of politics as much as philosophy. And all the variousness of approach and subject matter contained in Reason & Lovelessness dissolve under the author’s gaze in such efforts.

They reveal Hill’s project to have always been of a piece: a literary career that returns us to some primal sense of the writer’s task of offering courage, guidance and revelation — all of it shaped by an irrepressible, enduring delight in our fallen world.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Reason & Lovelessness: Essays, Encounters, Reviews 1980-2017

By Barry Hill

Monash University Publishing, 491pp, $39.95 PB