Rare verve and intelligence

Toni Jordan belongs to a special breed of writers whose affection for their home breathes off the page.

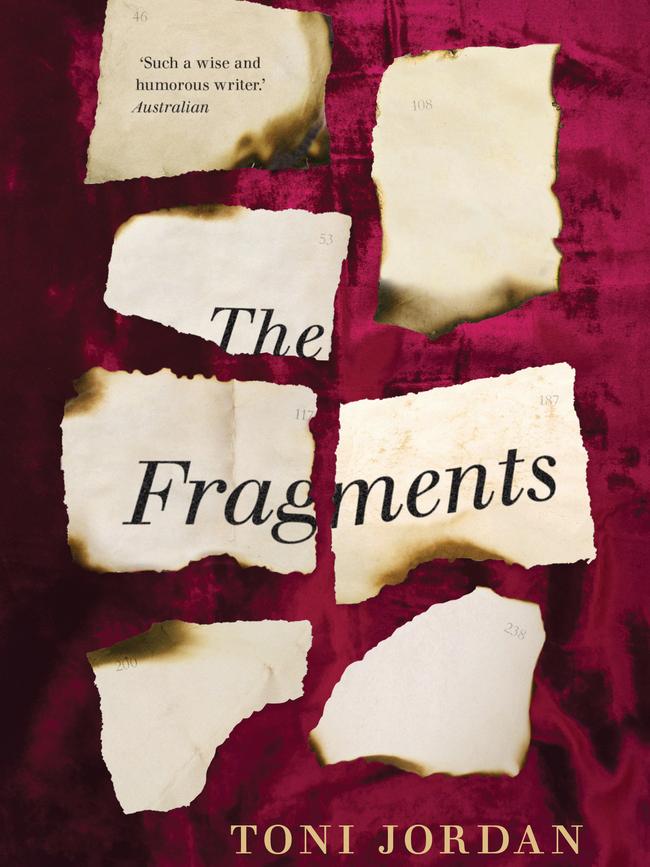

Think of The Fragments as a locket; one that opens to reveal the images of two very different women. They are divided by nation, sexuality, lived experience and the better part of the 20th century. Yet their lives are nonetheless clasped together — by a novel, of all things. One whose classic status is only enhanced by the fact no one alive has read it.

The book, The Hours, The Minutes — the narrative at the heart of Toni Jordan’s deft, engaging and often bittersweet new bibliomystery — exists only in fragments. It was the second fiction by Inga Karlson, an Austrian immigrant to the US in the years leading up to World War II.

When she died in 1938, in the same New York warehouse blaze that destroyed the only copies of her forthcoming book, alongside her gentleman publisher, Charles Cleborn (reputedly its only other reader beside the work’s typesetter), it provoked an outpouring of national grief. Karlson’s debut, All Has an End, was a Pulitzer prize-winning bestseller, after all.

An impeccable mash-up of Anne Frank’s diary and To Kill a Mockingbird, it made the author a rich woman and a household name. It is a lifelong love for All Has an End (she is named for its heroine) that draws Caddie Walker, a perfectly ordinary young woman living in Brisbane in the mid-1980s, to an exhibition of those few extant portions of its successor and the slender material afterlife of the author that is being held at the new state art gallery.

To say this is a consequential experience for Caddie is putting it mildly. On that day, she encounters a strange, acerbic, glamorously dressed old woman who quotes to Caddie from one of Karlson’s fragments. Except that she tacks on a line that does not exist.

Cue a crack in the door: which opens, for the first time since the author’s demise and despite a decades-old global publishing phenomenon devoted to the mystery of the novel, strongly suggesting that the key to the real story of Inga Karlson’s lost fiction lies slumbering in some leafy, suburban Brisbane street.

There is a precedent for a story as charismatic, bizarre and unlikely as that which Jordan tells. It was a 1982 short fiction written by David Malouf, A Traveller’s Tale, in which an arts council dogsbody sent to the tropics near Brisbane to lecture the locals on art and music is approached by a woman with a fabulous, even baroque, story. She, a rough-living, plain-spoken woman living in a forest shack, is the adopted daughter of the most famous Australian opera singer of the early 20th century.

Though it is set years before, the legitimacy of Malouf’s tale of a Melba-esque dame who takes into her care and then abandons to the rainforest a daughter of a Romanov grand duke rests on an idea of the Australian north that survives even into the period of Jordan’s novel, the butt-end of the Bjelke-Petersen years. It is a time and place where the most astonishing relics may rot in utmost privacy because the culture cannot see them for what they truly are.

Jordan takes this idea of invisibility and runs with it, establishing an interesting friction between two alternating narratives.

The first, moving between rural Pennsylvania and Manhattan during the 20s and 30s, tells the story of a young woman whose family is obliged to leave the land as a result of the Depression. She ends up working in a garment factory in her teens, where her father, a mechanic and overseer at the same workhouse, is a would-be roue with the factory girls and a domestic abuser at home. Her eventual escape to New York and a job as a waitress is a feat of heroism no less hard won for the modesty of its ambition.

The second returns us to somewhere more proximate: mid-80s Brisbane, a city poised between a tropic backwater past and a shiny, glass-and-concrete future. Our contemporary heroine Caddie is similarly stilled. Young, clever, but wounded by a failed romantic attachment to an older, handsome, yet ethically compromised academic. She has left the promise of postgraduate study and ekes out her days, happily enough, working in bookshop.

The encounter atThe Fragments exhibition changes all that. Caddie is obliged to return to the academic fold to track the woman down. This means renewed nearness to the caddish scholar — a return complicated by the presence of another handsome Karlson academic, less polished but more substantial for it. So are the lineaments of an old-fashioned romance novel grafted to the thrill of the literary chase.

Jordan is not a writer who deserves these generic simplifications, however. Like Liane Moriarty, she takes traditional, even shopworn, literary forms and invests them with uncommon intelligence and verve. The story of Rachel Lehrer’s escape from immiseration and masculine violence is as carefully researched as it is meaningfully inhabited; hers is by no means a typical life.

Jordan, too, belongs to a special breed of writers — from Jessica Anderson to Malouf to Ashley Hay — whose affection for Brisbane breathes off the page. She captures the city at a moment of change, with tenderness and clear-eyed alacrity.

That said, the main achievement of her novel lies elsewhere again. There is nothing harder than maintaining the pretence of an invented masterpiece, even obliquely. Jordan shows just enough ankle to convince readers that not one, but two great works issued from the pen of Inga Karlson. And she does so without recourse to false inflations of second-hand praise or parodic extracts, straining for genius.

The life of the author and the existence of her lost book are revealed here with a last-minute sleight of hand that is both satisfying and unexpected. Jordan evidently has a fair portion of her creation’s famed narrative skills.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

The Fragments

By Toni Jordan

Text, 336pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout