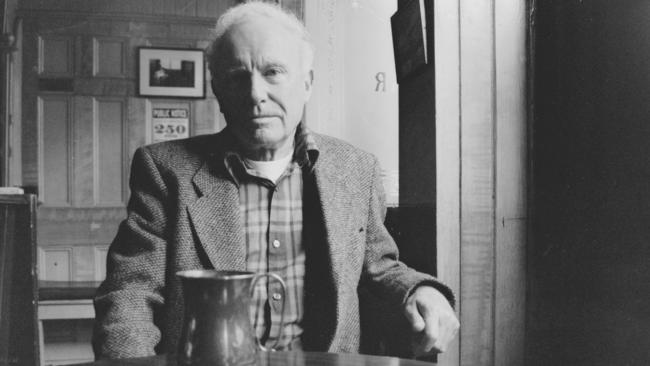

Randolph Stow biography by Suzanne Falkiner reveals a wounded man

Randolph Stow disliked biographers, but this first, full-length account of the writer’s life is essential.

For those of us who consider Randolph Stow one of the secret kings of 20th-century literature, not just a damaged wunderkind of its Australian branch, Suzanne Falkiner’s new biography of the writer inspires both excitement and trepidation.

The excitement arises from the knowledge that this is the first full-length life of Stow to appear. Finally we can see how the individual aligned with and departed from his work. Finally we have some clarifying sense of the wounds that shaped and animated Stow’s poetry and fiction. The trepidation arises from the same revelations. For a man so painfully withdrawn and socially awkward, an involute for whom privacy was a whorled shell about the self, this biography can feel only inimical, a crudeness committed against him. Falkiner has done an admirable, if impossible, job in these pages: the more she tells us, the greater that betrayal can feel. It is to her credit that she nonetheless identifies the horns of this biographical dilemma and impales herself on them.

“No doubt Stow would not have approved of this book,’’ she writes in an afterword. Though he acknowledged the benefits of some life-writing, he was not a fan of what he called, referring to the concentration in an old Shelley biography on the poet’s first wife, “chatter about Harriet”. Falkiner admits she has concentrated more on the personal aspects of Stow’s life than he would find acceptable. Nevertheless, she continues:

One also learns that even as he began to have intimations of mortality in the last decade of his life, Stow made no effort to destroy the wealth of surviving papers now archived in the National Library of Australia. He did not ask his closest circle of friends and correspondents ... to destroy the letters that they had kept over many decades. Even those works Stow felt he had moved on from, as juvenilia or merely frivolous, are intensely autobiographical fragments, documenting the narrative of his life and art.

“And while he hedged and blocked biographers in his lifetime,’’ she concludes, ‘‘he did acknowledge that such a book would be written after his death, perhaps more than one.’’

Mick is not, then, an elegantly oblique work in the vein of Gabrielle Carey’s Moving Amongst Strangers, released last year. Nor is it a critical or scholarly exploration of Stow’s oeuvre such as those undertaken in past decades by Anthony Hassall and Bruce Bennett. Its aim is at once more modest and more ambitious: ‘‘to contextualise the works within the broad arc of Stow’s life’’.

To that end, Falkiner has diligently mined the archive. She has read the fragments, notes and unpublished material, the letters and journal entries; and she has interviewed, where possible, family members and friends (aside from Stow himself, with whom she corresponded briefly before his death in 2006), as well as integrating a large amount of material assembled by earlier exegetes and potential biographers who did have access to the author. In doing so, she has captured many significant voices and sieved vast numbers of documents. If our desire as readers to move smoothly through her Life is sometimes impeded by the sheer mass of biographical data — if, as Shirley Hazzard put it, ‘‘assiduity edges out elan’’ in these pages — the picture we form is finally valuable because of its efforts towards totality. This is the life of Stow we needed: empirical where he was myth-making, expansive where he was elliptical, prosaic where he was poetically inclined.

Who, for example, can fully appreciate Stow without appreciating the author’s background? Like Patrick White, he was a child of risen colonial-era pioneers. His forebears were clergymen, lawyers and graziers in South Australia and the northern end of Western Australia. But the relatively modest Geraldton upbringing “Mick” Stow experienced (the big pastoral concerns belonged to uncles and aunts, the homesteads and senior positions to grandfathers and cousins, largely), suggests that his vision of Australian life was more grounded in ordinary experience than that of the more senior writer. White, born in London and raised in genteel captivity, would never have written to his mother, as Stow did: “Pull your head in, chook!’’

Mick was the son of a small-town solicitor; he spent his early education at local Geraldton schools before boarding at Guildford Grammar in Perth. What emerges from those chapters dealing with his early life is a love of the country that is deep and sincere — painfully so, when you consider his later self-exile. Falkiner includes whole clumps of Stow’s best known and most loved novel, 1965’s The Merry-Go Round in the Sea, without having to render back into fact more than a few geographic or social scraps, so closely did those memories hew to place and people. She quotes writer-friend Tom Hungerford in later years: “He’s still living there in his heart. He never left it, that’s why he recalls it so well.”

But not even Falkiner’s dutiful adherence to the record affects our amazement at how precocious Stow’s talents were, at how easily he leapt into print. After being kept in creative cold storage by the strict confines of Guildford, Stow published his first volumes of poetry and two tyro novels as an undergraduate studying law and then arts at the University of Western Australia. Most contemporaries grasping for another writer to set beside him reached for Francoise Sagan, who published her debut as a teenager. But a closer match is the French poet and novelist Raymond Radiguet, who completed two novels and several volumes of poetry before his sudden death from typhoid, aged 20, in 1923. But Radiguet tragically evaded the necessity of growing up to be a middle-aged child star. Again, our sense of wonder at Stow’s early promise is tempered by our knowledge of how ill-equipped he was to meet growing fame.

The young man who emerges from these pages is slight, mostly silent, self-possessed yet inwardly turned. He smokes and drinks with controlled abandon (‘‘I’m not an alcoholic,’’ he told a later interviewer, “but I do get awful thirsty’’) and uses the booze as a coping mechanism in the social realm. He has close male and female friends but there are limits to his intimacy. Falkiner makes it abundantly clear there was something excessive, even during an era when homosexuality was a crime and the blackest of social marks, in Mick’s resistance to the knowledge that he was attracted to men. It is fair to suspect that Stow’s response to his early success — a restlessness that manifested itself in travel and shifts in study or work, and in a regular and systematic neutering of daily reality through drink — was a way of leaving unmapped the alternate contours of his inner self.

Those travels took him from the remote Forrest River Aboriginal mission in the Kimberley — the region that inspired Stow’s third, Miles Franklin-winning novel, To the Islands — and eventually to Papua New Guinea, where, having briefly trained at the University of Sydney, he took up a post assisting government anthropologist Charles Julius and spent some months collecting language, myth and story alongside more mundane tasks in the Trobriands in 1959.

It is here, at the age of 24, that Stow’s personal demons catch up with him. Many have speculated about what exactly happened to Stow during this period: some suggested malaria, others psychological breakdown brought about by inappropriate sexual encounters. Neither appears to have been the case.

Falkiner does some serious grunt work in this section. Yes, Stow contracted malaria around this time — but the evidence suggests the disease was still dormant. It is more likely the side effects of his antimalarial medication, combined with a protein-poor diet and a bad skin infection, combined to unmoor the cadet officer’s health and sanity. When rumours that Stow and his superior were sleeping with men in the district for which they held responsibility coincided with news of a friend’s accidental death by drowning, Stow became distressed and attempted suicide. It was only a matter of luck that he failed to find a major artery with a series of razor blade cuts and so finish the matter.

Stow was shipped home to his mother under a veil of secrecy, and it remains questionable whether the scuttlebutt he was so disturbed by came from the locals or from his own febrile imagination. Perhaps one side of the writer’s psyche was trying to send a message to the other, and when the willed obtuseness of this other aspect of Stow could no longer resist the content of those messages, it ventured to sever lines of communications for good. It is fair to say that the psychological wounds sustained by Stow during this time remained fresh long after his physical scars had healed.

Though Stow subsequently returned to Australia and spent time in the country, with no plans to leave completely, these events — later to be explored with power in the 1979 novel Visitants — mark a split in his life and work.

Tourmaline, his fourth novel and his favourite, was begun in 1962 on the boat taking him away from Australia towards Britain. Its language and setting — intensely poetic, defiantly ambiguous — would mystify contemporary reviewers, but a similar divide was also evident in his second volume of poetry, 1963’s Outrider, a collection distributed between what are essentially before-and-after poem sequences.

In decades to come, Stow would increasingly find in his old ancestral patch of southeast England a place that answered to his need for peace and bucolic healing. And so his gradual reverse migration began.

Falkiner is an indefatigable registrar of detail for Stow’s wandering years. She tracks him through his immense North American road trip care of a Harkness Fellowship during the mid-1960s (Merry-Go-Round was written in a white heat during a couple of months’ stay in New Mexico), and then on to London and Leeds, where he saw out the 60s in the company of composer Peter Maxwell Davies and a cast of scholars, gypsies and scribes. We glimpse him drinking whisky with Thom Gunn and recovering with Sidney and Cynthia Nolan; being psychoanalysed by Anthony Storr and finding a new publisher in Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Though, as is so often the case, urban existence and accompanying physical illness creates in him a hunger for its opposite. More and more time will be spent in Suffolk, once the home of his Australian family on both sides.

“I don’t stay here for reasons of family piety,” Stow later insisted to Australian academic Laurie Hergenhan. Rather he saw his sojourn in the area as “a journey back from alienation, of finding a home”. No one who has read works that date from this latter period of Stow’s career, in particular The Girl Green as Elderflower from 1980, could doubt this was true. But it takes Falkiner’s sleuthing to show how and why Stow found a place in East Bergholt, Sussex, and then in nearby port town Harwich to be an approximation of that home.

Stow’s retreat into what he called “significant silence” was punctuated by bursts of effort. Having not published an adult novel since Merry-Go-Round in 1965, the author picked up his pen and, fortified by a fridge full of pork pies, he wrote The Girl Green as Elderflower in one month. The completion of his dark masterpiece Visitants followed almost immediately after. Falkiner shows us that his move to Harwich in the early 80s represented an embrace of invisibility. He sat in his local, drinking Adnams Real Ale with TheTimes crossword and Eastenders, to which he was addicted, playing on the TV.

Stow’s latter years included just one more novel, 1985’s The Suburbs of Hell, though the quality of his work never dimmed, only ripened in complexity. Falkiner leaves us with a picture of a man who became more comfortable in his skin — even capable in his final years of an extended relationship — but still divided. He came to call himself an Anglo-Saxon writer rather than Australian one. But when a friend once accused him of being one of those writers who escapes his homeland for more “civilised’’ nations, he replied: ‘‘I didn’t leave Australia for more civilisation, I left it for less.’’

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow

By Suzanne Falkiner

The University of Western Australia Publishing, 890pp, $50