The crisis that struck Greta Thunberg’s family

Teen activist’s mum has opened up on the trouble that struck her affluent family when Greta was just 11 in Our House Is on Fire.

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis

By Malena and Beata Ernman, Svante and Greta Thunberg. Allen Lane, 288pp, $39.99 (HB), $32.99 (PB)

-

There’s a vast island of rubbish floating in the Pacific Ocean. Known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, it consists of plastic and other debris trapped by the currents: a man-made scar on the sea.

A few years ago, Greta Thunberg cried as she watched a film in school about it. Her classmates were moved, too, but they reverted to their old behaviour as soon as they left the room, chatting about their next shopping trip or holiday abroad.

Greta, of course, did not.

Our House Is on Fire documents the period leading up to the start of her climate strike in August 2018, when Greta, aged 15, skipped school to protest about climate change outside the Swedish parliament. Her parents expected her to be “home by lunch”; instead she launched a global movement.

This is an English translation of a book by her mother, Malena, titled Scenes from the Heart, which has been updated by the whole family, including father Svante and younger sister Beata.

Malena describes its subject as “the crisis that struck our family — but above all about the climate crisis”. It makes for a fascinating, if slightly chaotic read, jumping between chapters on Malena’s career as an opera singer, Greta and Beata’s problems, and the climatic havoc humanity is wreaking on the planet.

At times, it feels like there is more than one book here: I was not especially interested in Greta’s mother’s mission to “take high culture down a notch”; I wanted to understand what drives the teenager who finally got the world to talk about climate change.

As Malena documents the family’s struggles — from Greta’s autism diagnosis to her own and Beata’s ADHD — she makes the case that such conditions can be an advantage.

“[These] neuropsychiatric functional impairments are not handicaps per se,” she writes. “In many cases, they can be a superpower, that out-of-the-box thinking you so often hear performers, artists and celebrities talk about.”

It means Greta sees the cognitive dissonance afflicting the rest of us about the environment. We may feel disgusted by that floating rubbish island, but we keep adding to it. This makes us all climate change deniers, she says.

“Greta has a diagnosis, but it doesn’t rule out the fact that she’s right and the rest of us have got it all wrong,” her mother notes. “She was the child, we were the emperor. And we were all naked.”

When Greta first found out about climate change, she recalls, “I remember thinking it couldn’t be true. Because if it were, we wouldn’t be talking about anything else.”

The family’s own crisis started when Greta was 11. They had been a happy, affluent group. Malena was a successful opera singer who won Melodifestivalen, the Swedish version of The X Factor; her husband was an actor. Suddenly, Greta began to cry all the time. Only Moses, her golden retriever, could comfort her.

Then she withdrew from the world: “She stopped playing the piano, stopped laughing, stopped talking and she stopped eating.” For two months, little food passed her mouth. When she did eat, she licked, sucked and chewed, taking tiny bites, and would consume only three foodstuffs: rice, gnocchi and avocado. Her parents tried everything. The experts at the eating disorder unit told them to count and time every meal Greta ate. It took two hours and 10 minutes for her to swallow five gnocchi.

Eventually, Greta announced she wanted to start eating again, and the painful process of returning her to health began. She was put on an antidepressant and was diagnosed, not with anorexia, but with high-functioning Asperger’s syndrome.

Meanwhile, sister Beata, a musical prodigy, had been overlooked. When she was on the cusp of puberty, she too started acting out, hurling abuse — and DVDs — at her mother. Even Moses cowered under the piano to hide from her. She was later diagnosed with ADHD.

These issues repeatedly overwhelmed the family. They struggled to find sufficient help, even though they were relatively privileged, having the time and money to focus on their children.

I am sure these chapters on the family’s struggle will be picked over by Greta’s critics. And she has a lot of those, both right-wing trolls and past-their-prime columnists who hate her — for what, exactly? Being a teenage girl with a brilliant mind and a platform?

They can’t draw analogies to Meghan Markle and a private-jet-style hypocrisy, as profits from the book are going to environmental charities. They can’t claim these are “First World problems”: the Bangladeshis will drown before we do.

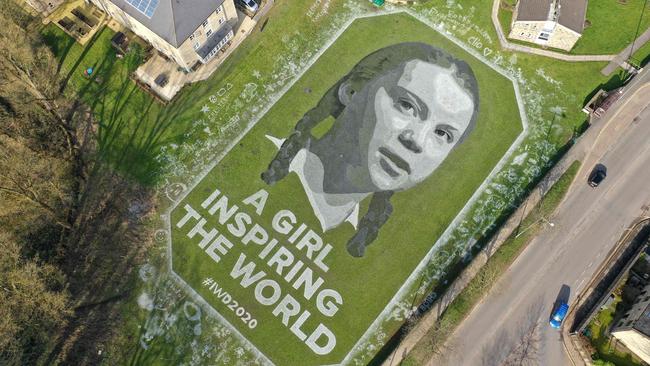

So their best shot against Greta is that the world has elevated a clearly unwell teenager to the status of global messiah. But this is also a book about finding purpose as a route to recovery: Greta seemed to thrive when she realised she wasn’t helpless, that she could make people open their eyes. A girl who struggled to talk to strangers without feeling sick was suddenly happily giving interviews to journalists.

The book ends before Greta becomes a global icon — and there are fair questions about how any teenager could handle that, child stars being the archetypal nervous-breakdowns-in-waiting. Yet it strikes me that this 17-year-old may be the true adult among us and the rest of us, always taking more, are the ones who are really behaving like spoiled children.

Rosamund Urwin is a senior reporter at The Sunday Times.

THE TIMES