Poitier’s journey expertly captured

Sidney Poitier’s return slap in 1967 drama In the Heat of the Night changed American cinema as America itself was changing in the tumult of the civil rights movement.

Sidney (PG)

Apple TV+

★★★★½

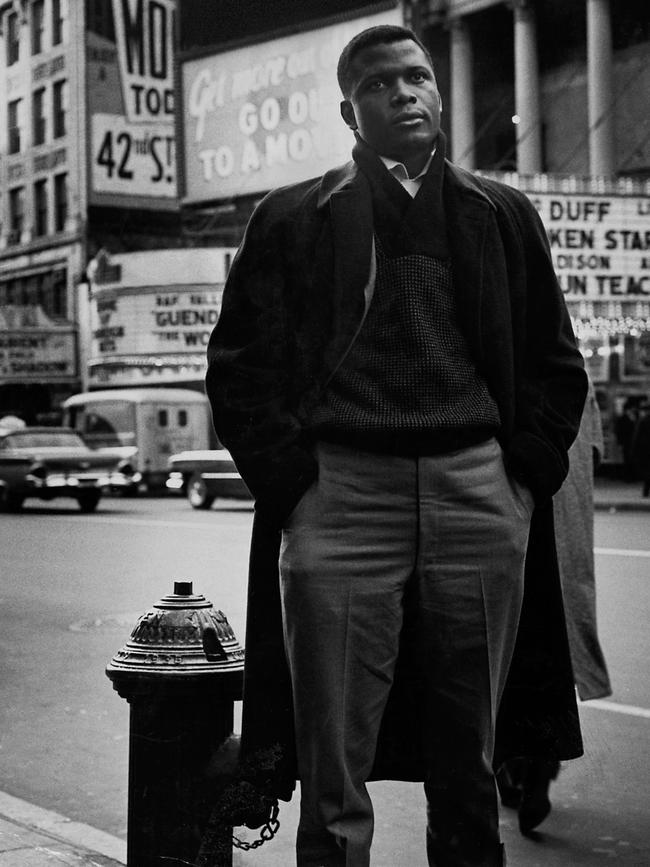

Like the man himself, Sidney, a documentary about the actor Sidney Poitier, is remarkable from beginning to end.

There is so much in this movie that is fascinating, revealing and inspiring that it’s difficult to choose which moment to go to first.

The star is Poitier, or Sir Sidney as the late Queen made him in 1974. He was interviewed at length before his death on January 6, 2022, aged 94.

He calmly recalls what happened when he was born two months premature. “My father came back to the house with a shoebox. They were prepared to tuck me away.”

Forgive a poetic interlude but on hearing that, Seamus Heaney’s heartbreaking poem Mid-Term Break comes straight to mind. “A four-foot box, a foot for every year.’’

In Poitier’s case the box was not needed. His mother saw a soothsayer who predicted, accurately, that her son would not only live but become famous.

That was Poitier’s start in life but I want to move forward four decades to the world-altering slap in the 1967 drama In the Heat of the Night.

A Mississippi plantation owner, Mr Endicott (Larry Gates), slaps the face of a black man named Virgil Tibbs (Poitier). Tibbs, who is a homicide detective from Philadelphia, slaps him back.

Louis Gossett Jr, one of numerous Oscar-winning actors interviewed, remembers the day he saw that scene on screen.

“You could hear a pin drop. It was the loudest silence I’ve ever heard in a theatre.” Morgan Freeman follows up. “You know what we all did?” he asks. “Yeah!” he answers, with a fist pump.

That return slap was not in the original script. Poitier insisted it be included. It changed American cinema as America itself was changing in the tumult of the civil rights movement. Seven months after the film was released, Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated, in April 1968.

In that single year, 1967, Poitier would also star in To Sir, With Love, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, each with race relations at their core.

Yet move forward again, less than a decade this time, and Poitier’s slap is “passe”, as Spike Lee puts it with a laugh. Blaxploitation films such as Shaft (1971), starring Richard Roundtree, were “all about kicking whitey’s arse”.

Gossett Jnr, Freeman and Lee are joined by Denzel Washington, Halle Berry and Oprah Winfrey, who produced this film, and other famous faces who grew up watching Poitier. Their verdict is unanimous: he was one-of-a-kind.

Freeman describes him as a lighthouse: always there, always shining the guiding light.

Winfrey cries as she talks about how her life would have been different without his presence. Berry smiles and puts it simply: “I wanted to marry Sidney Poitier.”

Barbra Streisand, who founded a production company with Poitier and Paul Newman, and Robert Redford join in. Redford says Poitier made him realise that “being an actor doesn’t mean you can’t speak out”.

Poitier’s near-lifelong friend Harry Belafonte, 95, is not interviewed for this film, but he joins in, with a lot of humour, through archival interviews.

Belafonte was first offered the role of Homer Smith in Lilies of the Field (1963). He turned it down flat. “It was a terrible movie. The worst script I ever read,’’ he says.

He then adds, of the actor who landed the role, “Sidney was wonderful in it.” So wonderful that he became the first black actor to win a best actor Oscar.

This 106-minute movie is directed by Reginald Hudlin, who has made previous documentaries about groundbreaking African Americans, such as music executive Clarence Avant (The Black Godfather, 2019).

The timeline traces Poitier’s premature birth in Miami, where his parents, tomato farmers from the Bahamas, were visiting at the time, to his teenage move to the US, where he worked menial jobs until he joined the American Negro Theatre, to his early films such as No Way Out (1950), Blackboard Jungle (1958) and The Defiant Ones (1958), a breakthrough role opposite Tony Curtis, to his Oscar-winning fame and career as a director of comedies such as Stir Crazy (1980) starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor.

The backdrop is close to a century of American history. A boy who grew up somewhere where everyone was black, he “had to switch my whole view of life” once in the US.

He recalls a white police officer putting a gun to his head – in life, not in a film – Ku Klux Klan members confronting family members, and regular white people remonstrating him when he had a job delivering parcels from a department store for daring to come to the front door.

Poitier refused to accept any of this. There is a scene in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner that perhaps sums him up. Poitier is a black doctor engaged to a white woman, which unsettles both families. Speaking to his father he says he loves him deeply (as Poitier did his parents Reginald and Evelyn) but adds, “You think of yourself as a coloured man. I think of myself as a man.”

Interestingly the lightbulb moment for Poitier as an actor was not on a film set but on the stage, in a 1959 Broadway production of A Raisin in the Sun. Gossett Jr was also in the cast.

“I knew for certain that I was meant to be an actor after the curtain came down on that opening night in New York,’’ Poitier says.

That play, written by African American writer Lorraine Hansberry, is now showing at the Sydney Theatre Company, directed by Wesley Enoch. After seeing this documentary I immediately bought tickets.

Poitier is revered by the actors who followed in his footsteps. However no one, including himself, pretends he is a saint. His long affair with Paris Blues (1961) co-star Diahann Carroll is discussed. His two wives and six daughters are interviewed.

Poitier himself talks about another criticism levelled at him: “According to a certain taste I was an Uncle Tom … a negro who fulfils white liberal fantasies.”

The writer James Baldwin understood the Uncle Tom viewpoint and hated films such as Blackboard Jungle, in which Poitier is the talented black student, even though he personally admired the actor.

This is a wonderful film. It is full of people who have made their own indelible marks in the movie business but, guiding them still, is the man in a black suit who talks straight to the camera throughout.

He should have the final word. He says something profound about life and death towards the end but I’ll leave that for viewers to hear, and go instead to 16-year-old Poitier, who was washing dishes at a New York diner and sleeping in toilets at a bus station. He scans the job ads in the Amsterdam News and sees one from the American Negro Theatre: Actors Wanted.

“I said to myself, ‘My god, they want actors? What would I be doing as an actor?”

Do Revenge (MA15+)

Netflix

★★★

The 1951 Alfred Hitchcock thriller Strangers on a Train, based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, has inspired numerous “let’s swap murders” movies, including the 1987 Danny DeVito-directed Throw Momma from the Train. Now it’s the loose basis of the entertaining American teen drama Do Revenge, directed and co-written by Jennifer Kaytin Robinson. It’s her second feature, following the 2019 romantic comedy Someone Great.

This 118-minute movie is a tad long but is well-scripted and strongly acted, with Maya Hawke, the daughter of Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke, especially good.

The two strangers who agree to do each other’s revenge are Eleanor (Hawke), who does question whether “do revenge” is grammatically correct, and Drea (Camila Mendes).

They are about to start senior year at an exclusive school in Palm Beach, Florida. Eleanor is new to the school and Drea is a scholarship student. Their classmates are rich trust fund kids.

Drea wants revenge on ex-beau Max (Austin Abrams), who she claims leaked a sex video of her. He’s the prince charming of the school but she thinks he’s a “fake woke misogynist motherf..ker”.

Eleanor, who is gay, wants revenge on Carissa (Ava Capri), who she claims told lies that ruined her life. “Drea and I are two wounded soldiers on the battlefield of adolescence,” she says.

“Claims” is an important word here. On the surface we start out with two teenage girls who don’t know each other agreeing to exact each other’s revenge but what follows has twists that Highsmith would be proud of.

Hawke, who has an ongoing role in the hit television series Stranger Things, is compelling. Eleanor’s emotional support animal is a bearded dragon she has named “Oscar winner Olivia Colman”. And while her therapist counsels that “hurt people hurt people”, her own view is, “I don’t think that applies to teenage girls. I think sometimes they are just evil”.

Which teenage girls she is talking about is the question on which this movie turns. She is a reader (we see her reading the Highsmith novel) and I have a feeling she knows the line from Hamlet: “Revenge should have no bounds.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout