Poetry reviews: Kate Tempest; Cassie Lewis; Caitlin Maling; Jacob Polley

Poetry is resurfacing from its cultural marginalisation by extending the repertoire of its narrations.

In Letter to Lord Byron WH Auden reminds us that the novel is “the most prodigious of all forms” though true examples are rare as “a polar bear”. He was reversing a hierarchy that once privileged poetry over fiction, with its propensity to delight and entertain, which was considered to compromise the capacity to enlighten or to inform. It is interesting to observe the history of this rendezvous between genres.

There’s no denying commercial limitations pose risks for contemporary poetry, a genre inherently resistant to narrative design, being principally in the service of language. Yet harking back to Aristotle, poetic tragedy provides a paradigm for all fictions, with elements of plot, character, thought, language and spectacle.

Poetry is at the moment resurfacing from its cultural marginalisation by extending the repertoire of its narrations. Performance poetry’s appeal to the fringe, to youth and the disenfranchised has extended into the mainstream, with spoken word poet Kate Tempest its unrivalled star. (In Australia we have Maxine Beneba Clarke and Candy Royalle.)

London-based Tempest has received prizes such as the Ted Hughes Award for innovation for Brand New Ancients and been named a Next Generation Poet by the British Poetry Society. Her voice is hypnotic, working-class and politically conscious, galvanising resistance in an increasingly divided country to British and European neoliberalism.

Last year she performed her new long poem Let Them Eat Chaos (Picador, 80pp, $22.99) live for the BBC. Epic and oracular, its universal address begins with a dramatic outer space prologue, drawing comparisons with Bjork or David Attenborough. Tempest then ventriloquises seven neighbours from a London street whose lives we enter when the clocks freeze at 4.18am and we peer through time’s portal.

She brings white, working-class London alive with synchronicity, as Virginia Woolf did with postwar, imperial London in Mrs Dalloway. However dysfunctional these characters may seem, facing substance-abuse, employment and housing issues, Tempest argues our identity is collective, hinting at how this constrains the individual, elitist voice of the lyric: “You and I apart are easier to limit. / The illusion’s so complete / it’s impossible to bring it into focus.”

The narrative tension deepens, moving from the third-person narrator to first-person soliloquies: from drug-addicted Jemma to “fast-paced, shit-faced, low-maintenance props man, Pete”; from Bradley, a ‘‘Manchester boy done good” to lovelorn lesbian Pious; or the alcoholic Zoe, who is packing clothes, posters, CDs, a stolen road sign and her “Che Guevara Bust” as she moves from her first-floor flat.

Tempest navigates the page powerfully, exploiting repetitions, with chiselled line breaks and cantos that pulse like a socialist protest march for “Poor kids shot dead /poor kids locked up /poor kids saying / this is the future you left us?” The struggle of the working class against corruption is contextualised by present-day colonial and environmental abuse, by ‘‘Indigenous apocalypse / decimated forests’’, with a petition to ethics deriving from John Steinbeck and Shakespeare: “The winter of our discontent’s / upon us.”

Tempest has worked across an impressive range of genres. With the help of her editor, Don Paterson, she has honed her technical craft on the page, her stanzas obeying poetry’s internal principles, disrupting into energetic chaos, then layering into cohesion. Despite the audience Tempest commands, what this book lacks is subtle variations in tone and thematic complexity. Let Them Eat Chaos is brilliantly bold; an urban, working-class long poem best delivered through live performance.

In The Blue Decodes (Grande Parade Poets, 102pp, $23.95), Cassie Lewis, a Melbourne poet who lives in New York, adopts entirely different narrative strategies. Her poems drift and digress through descriptions and memories of highways, train stations, towns and cities such as the Great Ocean Road, Queenscliff, Dublin, San Francisco, Melbourne, Brooklyn, Lake Michigan. The voice is univocal but discontinuous, inflected and interrupted by external objects, subtle observations, and suggested in the grammatical ambiguities of the book’s title. In many of the prose poems narrative works at the boundaries of practice, undermining the conditions of each piece’s exquisite existence.

In At the Terminal she writes: “Your mind’s subtle blueprint on my memory. Understood. I am free. You are free too: this is understood. ... Train terminal gunmetal grey and your breath, sweet contrast.”

A musicality runs analogous to the poetic text; the speaking voice is syncopated, improvised, sometimes rhapsodic: “Step lightly on the earth and it flows. I’m listening to that sublime wave of music in my head.” The lyric is offbeat, the semantics and syntax left-field, elusively rejecting authorial control but opening each poem to the world through anecdotes, dreams, incidentals, parataxis and ekphrasis.

In Opening the Box Lewis writes casually: “I noticed walls became stairs, after Escher’s Relativity / Do you recall when this blue shift occurred, how and why it could?”

In Black River the third-person narrative is tenderly realised as a portrait of a farm labourer dreaming of his girlfriend. In other poems second-person narratives break the autobiographical chronicles. “Be hospitable to strangers. / Sometimes you may want to give away everything you have.”

Chronology is broken with flash forwards and flashbacks as in Dialects: “You’ll be switching tapes / with one deft hand, on the waking dream-driver’s side.” These switches disrupt coherence; narrative conflict and suspense are diffused by supposition and the surreal. The Blue Decodes affirms the contemporary poetic anti-narrative. Lewis writes about experiences with delicacy, arousing aesthetic interest, and touching on environmental fragility: “Now I wade out into icy water — my home, my lake. / We have slept out in the open. We have no words.”

Written in the realist mode, Caitlin Maling’s Border Crossing (Freemantle Press, 108pp, $24.99) functions as a more structured book narrative. In free verse poems and sequences, Maling transports the reader from first-person chronicles in Houston back through memory to her childhood in Perth across the Nullarbor; from Oregon to Monterey to Las Vegas; from a wedding anniversary in Alaska to East Texas, Mississippi; from Virginia, Los Angeles to Shreveport. There are several registers at work: the auto-fictional components read like a travel diary with contemplative segments where landscape and language converge numinously.

There’s a surprising rhetorical quality to the verse as it risks received certainties and pushes ethical and ecological boundaries: “What makes a tree burn like that?”, or “Is it brave to refuse the home that’s offered?”, or the profound “Can grief come before the action?”

At other times a quiet irony informs meditations on landscape, memory, time and home, rejecting the simple binaries of exile and return narratives: “I wish to be where it’s taken / about a century to grow.” This thematic largesse is kept under restraint by Maling’s confident technique, allowing for variation in line lengths and effective enjambments. In February in Oregon she writes: “Moving between hemispheres means winter never seems to come / but just is and the sun moves with you.”

Maling’s method is observational and metonymic rather than metaphoric; her poetic narrative accrues crossing borders between physical elements, the seismic and erogenous, between personal histories and language, intersecting strands of knowledge, biology, physics, inquiry and memory.

In the contemporary elegy Herakles she writes: “The year after my parents divorce / pass in forty minute increments, / with breaks for us to feed and water ourselves.” This is a fine collection; it chronicles the material, discursive and the incremental in crossing borders, while eschewing the transcendental.

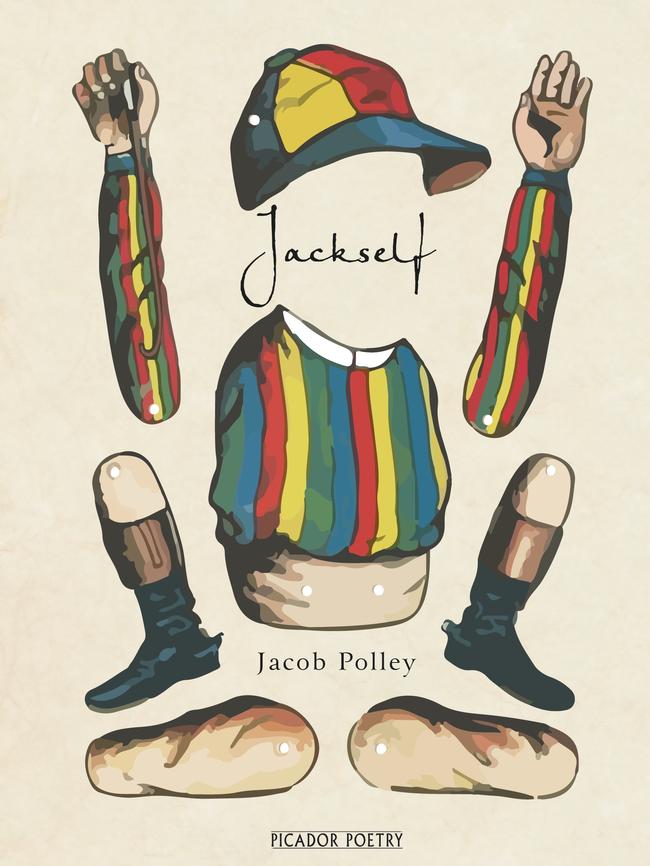

One of the most daring narrative experiments in recent contemporary poetry is Jackself (Picador, 67pp, $29.99) by British poet Jacob Polley, recently awarded the TS Eliot Prize. The title for Polley’s fourth collection, is borrowed from a highly wrought sonnet on the divine and profane nature of selfhood by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Perhaps, though, it is more accurate to say that Hopkins is one of many influences in this marvellous and disturbing collection that animates a childhood tragedy in the imagined Lamanby, in Cumbria, the poet’s home, using the language of nursery rhymes and folklore.

In the poem Every Creeping Thing there are echoes of Genesis and Robert Frost. Pagan themes are interwoven with the Christian myths of birth, dying and resurrection. The schoolboy friendship between Jackself and Jeremy Wren is central to this predominantly third-person narrative as it unfolds through allegorical portraits that could be heteronyms in the Pessoan sense.

Jack Frost, Apple Jack, Cheap Jack, Blackjack and other Jacks belong in a world where the hollyhocks and lupins whisper; the goose shed becomes a ghost shed where “Jackself comes to hunker down / in the gold straw” observing himself from “outside his life”, and “the black pond lies staring” and blinks.

The objectified mystery and dark ambivalence in these poems is redolent of Ted Hughes or Robin Robertson, but Polley’s imagery finds a more unconventional, organic cast as he underscores disquiet with rapture. The language is elegiac, richly laden with detail such as “the snail on its slick of light”.

Polley skilfully balances the euphony of vowels and consonants; there is delicacy, wit and ample variation conveying reciprocities of the ethereal and the dramatic: “by the mercury wires / of the spiders’ lyres and the great sound-hole of the night”.

In the chilling poem Pact, Wren hangs himself with a “dressing-gown cord / over the rafter in his bedroom”, leaving no note, as promised. There is almost childish banter between the friends at this critical moment, suggesting sadomasochism and the violence of concealment, disguise and spite: “you think I don’t have my own reasons / I’ll show you, he says.”

The broken world of innocence is only partially redeemed when Jackfrost slays the monster, Misery, who is terrorising the farmers and maids of Lamanby, but this cannot bring back his soulmate Wren.

Jackself is at once frightening and flourishing, a paean to the power of poetic language to transfigure reality and, for this reader, one of the finest poetic narratives in recent years, though I think we can expect more as we reap the richness and versatility of hybrid genres.

Michelle Cahill is a poet, writer and editor. Her most recent book is the short fiction collection Letter to Pessoa.