Poems That Make Grown Men Cry: read it and weep

AN important new book of poetry tells men it’s OK to take an emotional punch.

IAM not a weeper. I’ve never seen a male friend cry (aside from an unseasonable coincidence of ‘‘pollen in the air’’ after a screening of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King). Australian men get the crying dried out early. We’re told to ‘‘suck it up’’. Tears are mocked. And this is why the excellent Poems That Make Grown Men Cry, edited by father-and-son British writers Anthony and Ben Holden, is so important.

Here, world-class male writers, actors, directors and thinkers write candidly about the poems that bring them to tears. From the literary world, there are selections by Salman Rushdie, Clive James, Ian McEwan, Seamus Heaney and Christopher Hitchens. From intelligentsia, Rowan Williams and Richard Dawkins. From drama, Kenneth Branagh, Stephen Fry, JJ Abrams, Colin Firth, Daniel Radcliffe and James Earl Jones. And that’s just the start.

So what makes Darth Vader and Harry Potter cry? Injustice, nature, children’s lullabies — but mainly death, and its amplification of love.

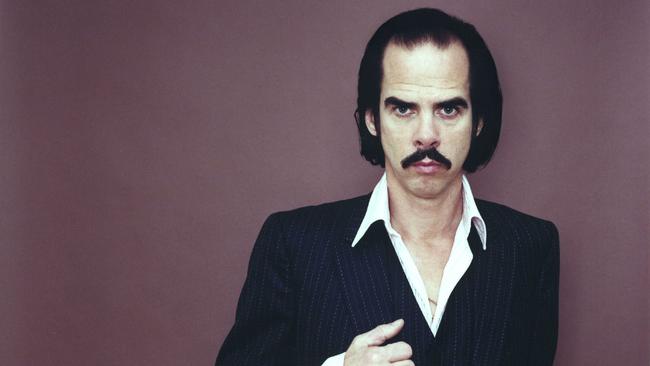

Les Murray’s The Widower in the Country ‘‘brings on the waterworks’’ for Nick Cave. There, grief radiates from a farmer’s ‘‘Christmas paddocks aching in the heat,/ The windless trees, the nettles in the yard’’ and his pointless day of work. For McEwan, it’s another Australian poet, Peter Porter, contemplating suicide in An Exequy, a lament for his late wife:

When your slim shape from photographs

Stands at my door and gently asks

If I have any work to do

Or will I come to bed with you.

Critic John Carey and actor Chris Cooper speak of the stunning pain of losing a child. For Carey Ben Jonson’s On My First Son is still ‘‘unsafe — to try to read aloud’’:

Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy;

My sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy …

Rest in soft peace, and, asked, say, ‘‘Here doth lie

Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.’’

Losing a parent moves Radcliffe and poet Benjamin Zephaniah. Radcliffe chooses Tony Harrison’s Long Distance I and II:

Though my mother was already two years dead

Dad kept her slippers warming by the gas,

put hot water bottles her side of the bed

and still went to renew her transport pass.

If that poem ‘‘doesn’t bring you up short’’, Radcliffe writes, ‘‘you have a heart the size of a snow pea!’’ Zephaniah cites Dylan Thomas’s Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, a poem of smashing, railing grief. It’s ‘‘the desperation in his ‘voice’ as he is willing his father to live … that moves me to tears’’.

And you, my father, there on that sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Men aren’t good at telling their mates they love them (sober, anyway). Nick Laird’s choice, WS Graham’s Dear Bryan Winter, speaks to this. Graham starts jokily:

This is only a note

To say how sorry I am

You died. You will realize

What a position it puts

Me in.

But later Graham’s banter breaks down as he questions whether anything of his friend and walking companion remains:

Are you still somewhere

With your long legs

And twitching smile under

Your blue hat walking

Across a place?

… I find

It difficult to go

Beside Housman’s star

Lit fences without you.

And nobody will laugh

At my jokes like you.

War makes Hugh Bonneville, Hitchens, Barry Humphries and James cry. The editors move from the naive beauty of Rupert Brooke’s The Soldier (‘‘If I should die, think only this of me ...’’) to Dulce et Decorum Est, Wilfred Owen’s satire on the Horatian proverb, ‘‘it is sweet and noble to die for one’s country’’:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs …

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

In Humphries’s selection, Siegfried Sassoon’s Everyone Sang, we have ‘‘a picture of … soldiers in a moment of emotional release’’:

Everyone suddenly burst out singing;

And I was filled with such delight

As prisoned birds must find in freedom,

Winging wildly across the white …

James’s choice is a poignant meditation on imminent death. In Canoe, Keith Douglas floats on an Oxford river with his love before leaving for World War II:

Well, I am thinking this may be my last

summer, but cannot lose even a part

of pleasure in the old-fashioned art

of idleness.

‘‘The moment that melts my eyes,’’ writes James, who is seriously ill, ‘‘is towards the end, when the young woman in the canoe is pictured as making her journey alone’’:

Whistle and I will hear

and come again another evening, when this boat

travels with you alone toward Iffley:

as you lie looking up for thunder again,

this cool touch does not betoken rain;

it is my spirit that kisses your mouth lightly.

Douglas uses nature for emotive force: summer’s day reflects the couple’s love, the rain-swept river elegises their separation in death.

Sebastian Faulks’s choice, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Frost at Midnight, uses nature for a different elegiac purpose. Coleridge sits by a ‘‘low-burnt fire’’, watching frost ‘‘perform … its secret ministry’’ as his ‘‘cradled infant slumbers’’. The peace of winter midnight brings him to consider, via symbolic landscape, how the ‘‘constraints of his own life shall underwrite the joy and liberation of his child’s’’:

… I was reared

In the great city, pent ’mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores …

… all seasons shall be sweet to thee

It is ‘‘poignant’’, Faulks writes, because ‘‘such moments were so few for Coleridge’’, a “shambolic man ... too often distracted by drugs’’. Paternal love ‘‘enabled the poet to find his true and immortal voice’’.

Hayden Carruth’s poem Essay, chosen by Jonathan Franzen, laments our destruction of nature. Carruth begins jokily: ‘‘So many poems about the deaths of animals’’: ‘‘Kinnel’s porcupine, Eberhart’s squirrel,/ and that poem … / about cremating a woodchuck.’’

Consequently, when Carruth reads about ‘‘a dead fox at the edge of the sea’’, he feels ‘‘deadened’’. Then,

I began to give way to sorrow …

because all these many poems over the years

have been necessary … This

has been a time of the finishing off of the animals.

They are going away — their fur and their wild eyes,

their voices.

‘‘The line that gets me,’’ Franzen says, ‘‘is ‘They are going away’.’’

A threat to civilisation and joy defines Rushdie’s choice. WH Auden’s In Memory of WB Yeats was composed as ‘‘war fell across Europe’’. The ‘‘dark cold day’’ of Yeats’s death is a national tragedy: the ‘‘Irish vessel lie[s]/ Emptied of its poetry.’’ But it speaks, more widely, to ‘‘the nightmare of the dark’’ where ‘‘[a]ll the dogs of Europe bark’’. Yeats’s work, Auden insists, must remain a beacon:

Follow, poet, follow right

To the bottom of the night,

With your unconstraining voice

Still persuade us to rejoice …

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

For Rushdie, who embodies the struggle of artistic enlightenment, ‘‘the last couplet … moves me to tears’’.

Before his death last year, Heaney selected Thomas Hardy’s The Voice. Hardy, newly bereaved, writes of being haunted by his dead wife’s voice:

Can it be you that I hear? ...

Or is it only the breeze in its listlessness

Travelling across the wet mead to me here ...

Thus I; faltering forward,

Leaves around me falling,

Wind oozing thin through the thorn from norward,

And the woman calling.

‘‘What renders the music of the poem so moving,’’ Heaney wrote, ‘‘is the drag in the voice, as if there were sinkers on many of the lines … When I get to the last four lines the tear ducts do congest a bit.’’

This collection might, as its publishing partner Amnesty International admits in an afterword, ‘‘be accused of sexism because it deliberately excludes women contributors’’, while “others may mock the very idea of men crying over poetry’’. But this is why the organisation supports it, as Amnesty director Kate Allen goes on to explain: the male contributors’ ‘‘emotional honesty is a healthy contrast to the behaviour that most societies expect’’, challenging the assumption that women ‘‘are more emotional — weaker — than men … [B]ottling up emotions can lead to aggression’’ and ‘‘gender stereotyping … upholds social inequalities that are a root cause of violence.’’

Poems That Make Grown Men Cry aims to ‘‘encourage boys, in particular, to know that crying (and poetry) isn’t just for girls’’. A worthy objective. My small contribution is to admit that this book made me cry. I was astonished by how it caught me in the guts. So read this collection, Aussie males, and have a good sob. You’ll be surprised how good it feels.

James McNamara is a Sydney-based reviewer.

Poems That Make Grown Men Cry: 100 Men on the Words That Move Them

Edited by Anthony Holden and Ben Holden

Simon & Schuster, 336pp, $32.99

THE POEMS THEY CHOSE

I’ll get up soon, and leave my bed unmade.

I’ll go outside and split off kindling wood,

From the yellow-box log that lies beside the gate,

And the sun will be high, for I get up late now.

From The Widower in the Country, by Les Murray

Chosen by Nick Cave

Well, I am thinking this may be my last

summer, but cannot lose even a part

of pleasure in the old-fashioned art

of idleness. I cannot stand aghast

at whatever doom hovers in the background:

From Canoe, by Keith Douglas

Chosen by Clive James

In wet May, in the months of change,

In a country you wouldn’t visit, strange

Dreams pursue me in my sleep,

Black creatures of the upper deep –

Though you are five months dead, I see

You in guilt’s iconography,

From An Exequy, by Peter Porter

Chosen by Ian McEwan

Though my mother was already two years dead

Dad kept her slippers warming by the gas,

put hot water bottles her side of the bed

and still went to renew her transport pass.

From Long Distance II, by Tony Harrison

Chosen by Daniel Radcliffe

He disappeared in the dead of winter: The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted, And snow disfigured the public statues; The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day. What instruments we have agree The day of his death was a dark cold day.

From In Memory of WB Yeats, by WH Auden

Chosen by Salman Rushdie

So many poems about the deaths of animals.

Wilbur’s toad, Kinnell’s porcupine, Eberhart’s squirrel,

and that poem by someone — Hecht? Merrill? —

about cremating a woodchuck. But mostly

I remember the outrageous number of them,

as if every poet, I too, had written at least

one animal elegy;

From Essay, by Hayden Carrut

Chosen by Jonathan Franzen