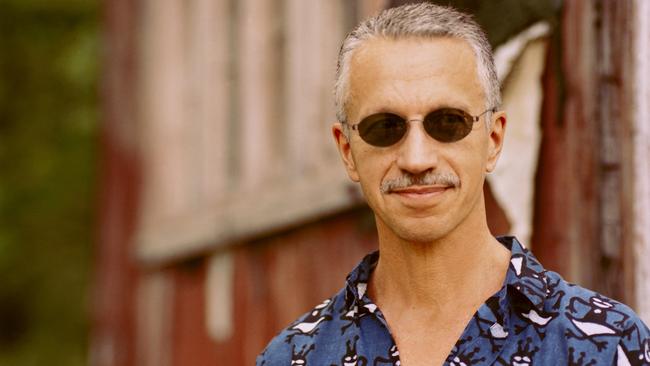

Pianist Keith Jarrett always finds room for improv

TO experience the creative rush of Keith Jarrett is to appreciate the fragile intimacy that develops between audience and performer.

IT was a Friday night in Cologne, and everything was going wrong. Keith Jarrett, not yet 30 and already known for his electric experiments with Miles Davis, was feeling awful. He had come to play a concert of solo piano, and even though it was being recorded it wasn’t clear whether there would be a show at all.

He had hardly slept the previous night. He had spent the day on the road. At the venue, all seemed fine except for one detail. Jarrett’s request for a Steinway had been ignored and the piano provided sounded “like a very poor imitation of a harpsichord or a piano with tacks in it”. The clock was ticking.

Jarrett and the boss of his record label, Manfred Eicher, dashed off to eat at an Italian restaurant. The food was late, the restaurant was hot, and when Jarrett walked out on stage a few minutes later, having quickly gulped down his meal, he was falling asleep. Then he began to play. His performance that evening, January 24, 1975, became known as the Koln Concert. It has sold more than three million records, a remarkable figure for improvised piano music, and is generally regarded as Jarrett’s most successful album. Some of his other albums may scale greater heights from an artistic point of view, but there’s something about this one that resonates to all kinds of listeners.

A few minutes in, and it’s clear something special is happening: the music has a warmth that is welcoming, and within the folds of a virtuoso at work is a folkie sense of abandon and charm and musical storytelling of the highest order. It makes it even more remarkable to consider the frictions behind the scenes, how Jarrett produced 70 minutes of magic despite all that discomfort. The conditions could hardly have been worse; he plays mostly in the middle register because the rest of the piano sounds so tinny, but still pulls it off. His biographer, Ian Carr, says Jarrett was taking refuge in music from external stresses. Or maybe he just got lucky and played well despite everything.

All this is relevant when you consider what has taken place in subsequent years. A child prodigy, a master of the jazz and classical realms whose improvised concerts have a devoted following around the world, 69-year-old Jarrett also has become known for his intolerance for sub-par performance conditions. His concerts come with rules that go well beyond the quality of the acoustic and a regularly tuned (Steinway) piano. The audience is bound to specific standards of behaviour: no photographs, no coughing. In other words, absolute silence.

When this compact breaks down, the results can be disastrous. In 2007, Jarrett became exasperated in Perugia, where he was playing with his trio as part of the Umbria jazz festival. It was an outdoor venue, and Jarrett shouted at the audience to stop taking photos. He called them assholes. Organisers banned him from the festival, only to invite the trio back last year. By all accounts, that show was equally bizarre. Spotting someone taking photos, Jarrett demanded the lights be lowered, and the trio played two sets in near darkness.

It’s easy to mock this stuff, and Jarrett does himself no favours with his often imperious manner. His antics mean no Australian promoter would want to take the risk of bringing him to town (even if that were an option: Jarrett is unlikely to want to make the long trip). Few performers command such reverence on stage. Even the most forgiving fans roll their eyes when he starts to complain — yet they keep going back, again and again. I know this because I was there in Perugia in 2007, having travelled across the world for a concert spoiled by arguments with the crowd. Five years later, I flew to Japan to hear him play solo piano. It was a transformative experience, so last month I went back to Japan for more, only to find myself watching, yet again, another meltdown.

Before condemning Jarrett as precious or pretentious, perhaps we should pause to consider the broader picture. These concerts raise subtle but important questions about the nature of live performance, the process of improvisation and the extent to which audiences and artists can reasonably make demands of each other. How do you define that relationship between him and us? Is Jarrett an entertainer, a servant to a paying audience? Or does the balance fall the other way, where the privilege is ours to hear him play?

The second stop on his Japanese tour this year was Osaka. Expectations were high: before the show, audience members even lined up to take photos of the poster outside the venue. His first piece was thrilling. It lasted about 20 minutes, and contained traces of Russian classical styles in his elaborate composition. But then the coughing started, and Jarrett lost his concentration. There were false starts. He walked off the stage. He pretended to cough on the piano. He played chopsticks. After an audience member called out something about the capabilities of genius, he returned to the stage and said: “Find me a genius who isn’t distracted. You won’t. I’m only human.” False starts and interruptions and coughs continued. The atmosphere was gone, and Jarrett settled into first gear to round off the show. His version of first gear happens to be pretty remarkable, but the angry crowd that demanded answers at the office door after the show clearly felt cheated.

Three days later, in Tokyo, was an altogether different experience. Word had travelled from Osaka: the woman next to me nervously drinking cough syrup before the show, the announcement in two languages asking us to stay silent and not to cough. The audience obliged, and it was impressive to hear several thousand people barely moving, barely breathing, for two hours.

Jarrett returned the favour with an inspired explosion of creativity — and four encores. It felt like he was in the zone. There were frenzied flights of passion up and down the keyboard, moments of yearning, moments of whimsy, passages of deep gospel grove and angular attacks. Several segments were brought to an end as soon as ideas had run their course. I held my breath during silences and savoured the lot: the harmonies, the atonalities, the way he let his left hand dance, how he caressed the upper notes of the piano, how he let notes ring out around the room. Jarrett’s repertoire has broadened considerably since the 70s, and he drew on multiple traditions and styles to take us on a magical odyssey that extended for more than two hours.

And it’s here, in the nature of the music, and the process behind it, where some insights into his behaviour can be found. For this is not jazz, where improvisation takes place over a specific framework, nor is the context a classical one, where performers tend to interpret the notes of others. Jarrett is unique in his ability to produce instant composition at this level with such elegance and craftsmanship.

He has spoken about how he tries to achieve a meditative state in these concerts, to clear his mind before playing. There’s an alchemy at work, to be sure, and the demands on the performer, mentally and physically, are immense. And Jarrett remains utterly exposed, creatively, from beginning to end.

In 2006, he gave a revealing interview to The New York Times to coincide with the release of The Carnegie Hall Concert, a solo album. Asked about audience interruptions, he said it was like being commissioned to dive into water and then, as you descend, you panic as air gets into the mask: “It’s not a personality failure on my part.” He went on to say of the Carnegie Hall performance that the audience was a part of the music, and always is. “There was a conversation between the audience and myself over the entire span of my career,” he said.

It’s true. From the audience, there are times when you feel right up there with him, sitting by his side as he searches in the dark for what to play next. Ours is a highly strung intimacy that makes it relatively easy to trip him up with a cough, a rustle of paper or, god forbid, the flash of a camera. So perhaps, for us, the price for experiencing the creative rush is the acknowledgment that sometimes this balance will be off, and that the thread will break away.

With Jarrett, the relationship between audience and performer is tense but vital. Jarrett knows this, too. Why else would he keep inviting us to join him? It’s the reason most of his solo albums are recorded in front of an audience. The recordings, after all, are only of secondary importance, since they can never replicate what it’s like to be there, as witness to the ephemeral magic of spontaneous composition. It meant I was right up with him, close to the stage in Tokyo last month, as he searched his mind after playing two sets of music. He stood blank for a few seconds, looked at the audience, then turned back to the piano. Still standing, he leaned inside and whispered to the strings: “What next?”