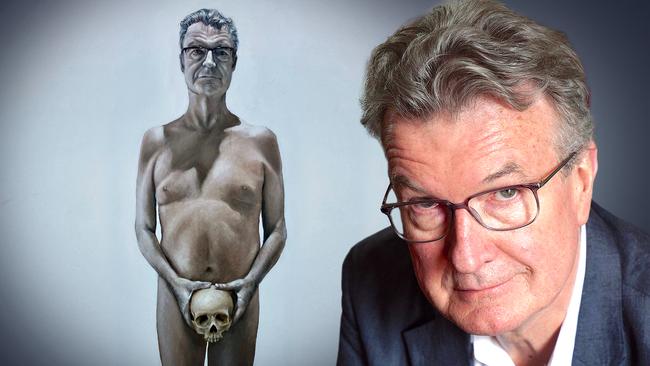

Peter Goldsworthy wrestles with his own cancer

Peter Goldsworthy has held the hand of many a cancer patient. Now, emaciated but as funny as ever, he’s documenting his own battle — and the most important lesson he’s learned in the process.

Jeff Estanisloa

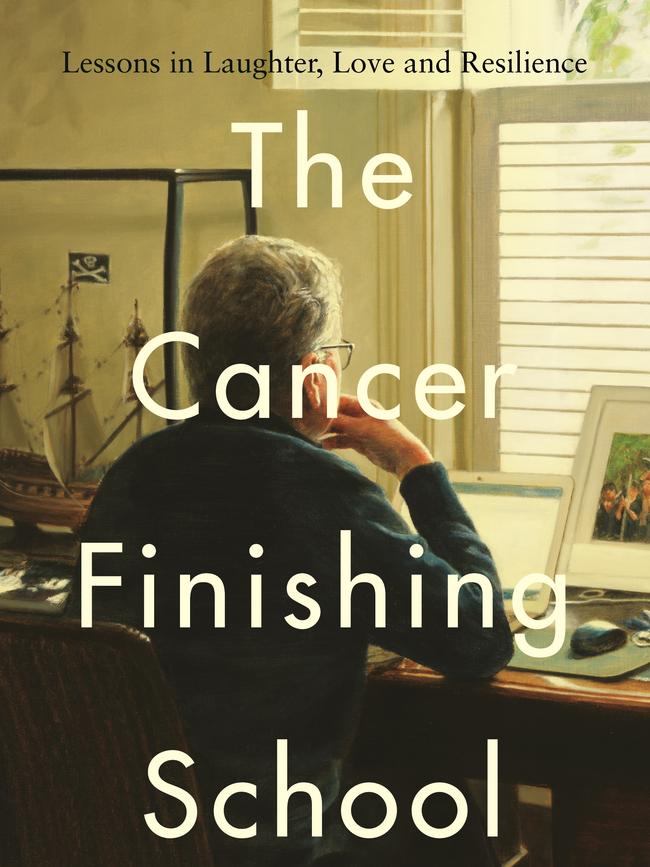

Peter Goldsworthy will be known to many readers as a poet and writer. He’s also a medical doctor, who has held the hand of many a cancer patient. Now he has been diagnosed with cancer. Goldsworthy’s new book, The Cancer Finishing School, is his account of the experience. He’s included some poems, and I’m delighted to publish two of them, today.

The first is called Tomorrow. Read them below, and then tell me you don’t feel the same about tomorrow. Did you not love her, the first time you met? Is she not at least close to the last thing you think about, before you go to sleep?

I’m also publishing Haiku, More or Less.

I am not your host, cancer, I am your suicide vest. I’m taking you with me.

I do love that idea. Goldsworthy doesn’t guarantee a happy ending in his book. “That would take away the suspense,” he says. “Every good story needs an element of suspense.”

There’s plenty of suspense with cancer, and plenty of mystery. What kind do you have? How did you get it? What stage is it at? Most cancer stories also feature rushes of excitement: Am I in remission?

Maybe! Maybe not. I hope for good news for all of you.

If you didn’t already know, Goldsworthy’s book confirms him as a funny man. There are plenty of jokes, many of which he picked up from cancer patients. I also loved the chapter where he goes to a beach house with his beloved, Lisa, to do a little skinny-dipping – or “skin and bone dipping” since he’s emaciated.

Lisa takes some pictures as he emerges from the surf, and he can’t get over the sight of himself as a “strange, pale-pink, angular, bald creature from the deep.” She thinks he looks like some kind of unknown marine creature, or else he’s a “blubber-free mammal” who finds the night air cold on his bald nut.

There’s some lovely language right there.

Toward the end, he’s grateful not for the illness, but for the diagnosis, because he’s been given time to think about death, which is of course coming for all of us.

“The lucky, like me, get to see it coming,” he writes, “Death offers a prism, a magnifying glass, through which all the wonders of life can be seen and felt with heightened intensity.” It is, he thinks, like getting “a new pair of lenses, a last pair, to see us out.”

The most important lesson of the life he’s lived so far?

“It hardly bears repeating,” he says, and yet he feels inclined to write the answer down, 100 times a night.

Love. Love is the answer. Glorious book. Go get one.

***

Tomorrow

I loved Tomorrow

from the first day we met:

her secret promises,

her sweet backward glances.

She was always the last thing

on my mind before sleep.

She made me feel special.

Often we talked all night:

her hopes and plans for us,

our future together.

Years passed, passion faded,

I began to take her for granted.

At times she disappointed me,

at times we quarrelled,

but when I needed a hand

hers was always there for me,

reaching back over difficult

midnights, hauling me across.

When did we begin to grow apart?

When did she start telling me lies?

When did I wake to find

she had no time left for me at all?

- PETER GOLDSWORTHY

Haiku, More or Less

Less is More

If you want to write

a cancer memoir, please consider

a haiku instead.

Haiku

Haiku? Cigarettes

smoked after the unspoken

has fucked with your head

River

If time is a river

it washes our each soft pebble

rougher not smoother.

Prayer

I needed to pray,

but felt embarrassed. What if

Someone was listening?

MidLife Career Change

What if cancer is not

just another job, like dying,

but a whole new career?

Parasite

I am not your host,

cancer, I’m your suicide vest.

I’m taking you with me.

Last wish

When I die

and go to Hell

Promise me

You’ll come as well.

As ever, you can reach me at overingtonc@theaustralian.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout