Peter Carey explores inner workings

PETER Carey's new novel is a story of secret love, desperate loss and the healing qualities of a beautiful mechanical bird.

IN 1637, philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes published his Discourses on Method, a book whose radical scepticism and mechanistic world view did as much as any other to shape the modern age. Among many arguments in its pages was a suggestion animals were merely complex organic machines.

"It is nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs," he wrote of animal instinct, "just as a clock, which is only composed of wheels and weights is able to tell the hours and measure the time more correctly than we can do with all our wisdom." Only humans, who have language and so reason, were exempt from this downgrade.

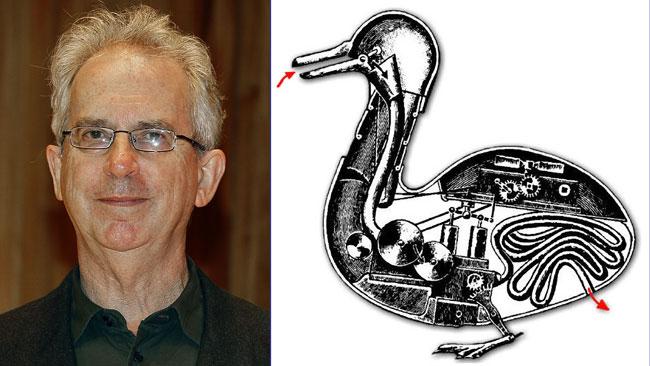

Europe's clockmakers took Descartes' vision literally in the centuries that followed. They designed biomechanical creatures in which cogs and wheels replaced muscle and bone. Best-known of these was Frenchman Jacques de Vaucanson who, in 1739, built an artificial duck that waddled and ate food it later appeared to excrete. For a time Vaucanson's defecating duck was the most famous bird in Europe, its thousand moving parts working proof of Descartes' contention.

It is typical of Peter Carey's peculiar gift for narrative that his new novel should partly draw on this historical curiosity. The low comedy of the creation -- its ingenious vulgarity -- is of the same kind long used by Carey as ballast for his more airy metaphysical flights. And the technical wizardry involved in the bird's design and construction is of a piece with the author's own intricate enchantments: devices made from nothing but imagination and words. That his often impeccable new fiction should end up as over-engineered as the machines it describes, however, says something about the limits of ingenuity.

Despite its concerns with gadgetry, The Chemistry of Tears begins as a wholly organic human story. Catherine Gehrig is a horologist (a maker of watches and clocks) in her late 30s employed by London's Swinburne Museum, an invented yet plausible organisation that could well be the British Museum's lesser-known twin. In the novel's opening lines she learns that Matthew Tindall -- a work colleague and the married man with whom she has maintained a long, loving, and apparently discreet affair -- has died suddenly, felled by a heart attack on the Tube.

The effect on Catherine is devastating. She is floored by grief but has no social outlet for its expression. To let herself go would be to expose her pride (fierce) and privacy (cherished) to public ridicule. And it would not only mean personal shame but professional suicide: an inconceivable outcome since Catherine's work, first glimpsed at the side of her grandfather, an East End watchmaker of the old school, is the other love of her life. She does not even have the old consolations of religion to draw on. "Neither I nor Matthew had time for souls," she claims, and later adds:

What peculiar people we had been, he and I, rationalists but sensualists, always so proud and careful of our bodies, knowing our lives were finite, acting as if we were eternal.

A powerful bind, then, and one Carey handles with customary deftness, even while choosing a first-person narrative approach. His decision means that we, the readers, are pitched into awkward intimacy with her grief. It is we alone who witness an hysteria barely held in check by daily industriousness, and nightly by a bottle of vodka.

That is to say: us, and one other. It turns out that Eric Croft, head curator of horology -- a smooth-suited scholar and connoisseur Catherine has never trusted -- not only knows of Catherine and Matthew's six-year affair but helped enable it. Croft confronts Catherine with this information. He offers to cover up the couple's email correspondence, and to have her temporarily seconded from the main museum site to its grim West London annex. His final kindness is a mysterious project: a disassembled automaton of extraordinary complexity and craft for her to restore and, if possible, reconstruct. Her mourning will unfold in relative solitude, in the presence of a great distraction.

If this sounds too pat, it is. The logic of grief is, of course, no logic at all, and Catherine responds to the plan by lashing out at her would-be protector. It is only an instinct for self-preservation and a need for the narcotic effect of work that keeps her trudging to her subterranean studio each morning to sort screws and polish cams. "What can we do?" she asks of herself, laying out the tiny pliers and cutters, files and saws, which are the tools of her trade: "We must live our lives."

This would be a gloomy undertaking in the hands of a novelist other than Carey. Luckily he remains a writer with an unerring sense for the perverse in human affairs. The continual and guilty delight of these early sections -- the funniest, most cutting and anarchic -- is that they acknowledge what we know to be true but dare not say: grief gives delirious licence to all those behaviours we otherwise hold in check. Catherine whirls through those strict codes of social politesse, bureaucratic nicety and professional ethics that govern her role like a drunk through traffic, blessedly unscathed.

She takes vicious satisfaction in pushing the boundaries of Croft's willingness to shelter her from the consequences of her actions, and she breaks her own rules of conduct by reading those emails of Matthew's that he passes for Catherine to delete. And the wary daughter of an alcoholic applies to drinking the same dedication that she gives to restoration work (by way of explaining Carey's uncharacteristic English setting, our hungover narrator observes: "I do love my country's relationship to alcohol. How would I ever exist in the United States? I suppose I would have grief counselling instead.")

Most significantly for the narrative, during this time out from bourgeois sobriety and self-constraint she steals work materials relating to her project -- a series of notebooks, filled with impeccable copperplate handwriting -- and takes them home to read. Their exquisite hand belongs to the Victorian gent who commissioned the mysterious automaton, and the notebooks describe the story behind their making. Though the adventures of Henry Brandling take place some century and a half earlier, in a very different world to Catherine's, in many respects he has a similar tale to tell. His notebooks become a tandem narrative to The Chemistry of Tears. We read his words, as if over our first narrator's shoulder.

It is odd that this strand of the novel should prove less engaging than its present-day echo, since it indulges in just the sort of antic, picaresque and broadly eccentric historical revels so winning elsewhere in Carey's body of work. As it is, Henry Brandling is a Wodehousian innocent dropped into our fallen world. Undeniably a good man, as a narrator he is also maudlin, aloof, cranky and dispirited. The only constant in his character is a obsession with the making of a replica of Vaucanson's famous duck, a basic design for which has just been published in an English magazine.

Brandling is a wealthy man. His family made its fortune by speculating on the success of George Stephenson's steam locomotive. However his home is an unhappy one: one daughter dead in infancy, a wife alienated from her husband in the wake of her despair, and a sickly son, already marked out by tuberculosis. Brandling's inspiration, driven by a sweet madness, is that the reconstructed duck would be a device of such joy to his son that it would heal him, and thus the whole family. And he sets off for the Black Forest region of Germany, famed for its clockmakers, with a bulging purse and the plans for the mechanical duck in his hands.

It is an achievement that only becomes clear on re-reading, how neat the author is in making these disparate stories rhyme across the years. Both Henry and Catherine mourn the loss of a loved one (though for childless Catherine, Henry's insistence on the primacy of parental love is galling). Both turn to the making (or remaking) of an automaton as a kind of grief-work (he with ludicrous Victorian optimism; she with corrosive modern pessimism). Each ends living in close proximity to a beautiful, talented young person.

For Henry, it is the angelic and fatherless Carl, who assists the mysterious German horologist Sumper -- part genius, part madman -- in his recreation of the duck.

Catherine, meanwhile, is obliged for her sins to suffer the presence of Amanda, a beautiful and highly strung Courtauld graduate, as her assistant. Amanda is capable and thoughtful in her duties, but she is nonetheless an impediment to the free play of Catherine's despair. Moreover, she may be a spy installed by Eric Croft to monitor an unstable employee.

Catherine's mounting paranoia regarding Amanda's role marks a radical change in the novel. Up until now the twin plots have simply rhymed. But as the completion of the automaton in both past and present approaches these narratives mesh like a series of gears: past and present begin to inform one another in ways that indicate madness on the part of the twin narrators, or else point to diabolical connections. In the birth of technological modernity, The Chemistry of Tears seems to imply, lie the seeds of planetary destruction.

The quantum expansion in concerns and interconnections here is occasionally thrilling, sometimes terrifying, yet mainly demoralising in its complexity. This is not to say that Carey isn't spot-on in sensing abomination in the uncanny resemblances between living creatures and automatons, as well as between the human mind and its new digital abstractions (not for nothing does his narrator call smartphones "Frankenpods"). No one is wrong to see something infernal in the five million barrels of oil that spew into the Gulf of Mexico as the novel's narrative unfolds.

And yet. This wider critique sweeps away the stories it is meant to be arguing on behalf of. There is a an intimate mode of communication that exists between a novelist and his readers, and Carey's novel eventually moves out of that narrow band. It is a shift that begs the question: why have those philosophical, political and ecological concerns -- often prominent in Carey's work; always an engine of comedy and outrage when they are -- become decoupled from the human scale of his fiction?

There is significant irony in the possibility that this novel, so ambivalent about computers, has been led astray by the web. The siren call of its hyperlinks, jumping indiscriminately through time and space, have led many a lesser writer than Carey into narrative chaos and confusion.

"It was grief of course," wrote Carey in 1991's The Tax Collector, "but grief does not stay grief forever. It changes, and in this case it must also have changed, although into what is by no means certain." The passage of grief, its metamorphosis from one thing to another, is the subject of The Chemistry of Tears worth clinging to. There are things we never learn about Henry Brandling and his months in the gingerbread villages of the Black Forest. But we retain from his story a sense of the utopian potential for machines to restore instead of destroy us. The emergence of Catherine Gehrig from secret widowhood into the sane light of the everyday through the human agency of one author's psychological acuity, comic verve and empathy is no less splendid a vision.

So forget for a moment the apocalyptic grumbling to which Carey has momentarily surrendered. His achievement is to disentangle Catherine's single hurt from a world "filled with millions and millions of hearts, like gnats and flies, each with its own private grief like this one".

The Chemistry of Tears

By Peter Carey

Hamish Hamilton, 288pp, $39.95 (HB)

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.