Peter Brook brings The Suit to Adelaide’s State Theatre Company

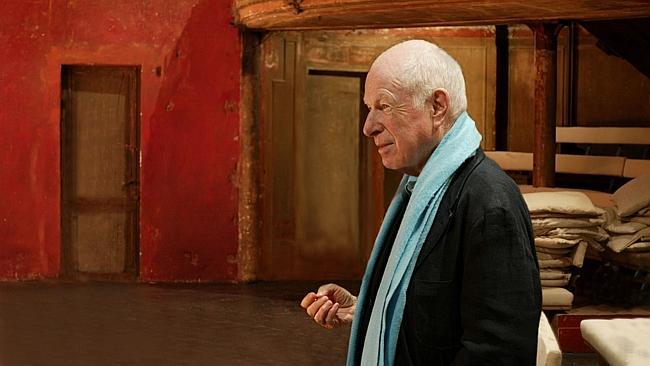

NEARLY 90-year-old Peter Brook, one of the world’s great theatre directors, is bringing his work to Adelaide.

PETER Brook picks up his glass of water from the table and holds it in the air between us. “Imagine,” he says in his refined and pleasant way, “if I told you a story about a person in a boat who is looking down at the sea.”

Having spent the best part of an hour in an upstairs room at London’s Young Vic theatre mesmerised by Brook’s genteel demeanour and cool blue eyes, by his long but never long-winded answers to questions, I’m suddenly seeing waves and currents in the tumbler the Englishman — the most influential, perhaps the greatest, theatre director of our time — is offering for my perusal.

“And then this person gets into a spaceship and goes right to the moon.” He moves the glass towards the ceiling. “So you see, when you have actors with their wits about them working together with their imagination flowing, there is no right or wrong convention.”

Brook, 89, has never been one for rules. While his 1968 book The Empty Space, with its opening lines “A man walks across an empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged”, set a template for modern theatre, introducing techniques then deemed radical, he wasn’t insisting that anyone should copy them.

50 YEARS OF THEATRE AND THE ARTS IN THE AUSTRALIAN

His quest for a sort of simple intensity in the theatre, for an in-the-moment communion between performer and audience, is a journey on which people accompany him. He’s a collaborator, he says. He doesn’t like the word director. A sort of organised spontaneity infuses Brook’s rehearsals and productions; a right to fail, the basic tenet of all experimentation, is maybe his only proviso. Find your own way, he tells the acolytes and wannabes who seek his advice. Just realise it’s an ongoing process.

“In the 1960s I threw myself into every sort of excess, in life and in the theatre,” he says after leaving his walking cane by the door and coming over to introduce himself, hand outstretched and eyes crinkling at the corners; older and smaller now, more sage-like, but on trend in a yellow scarf, brown V-neck and fitted dark green combat pants.

“For years I used every theatrical device going,” he continues. “Scenery. Costumes. Lighting. Revolving stages. But as with everyday life, as with food or drink or drugs, I gradually understood that too much is of no interest.” A smile. “I began to see that the human being is richer than the greatest stage effect.”

With books, films, operas and more than 50 plays to his name, Brook’s career highlights are many. Landmark works include his 1963 film adaptation of William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies, in which he directed a cast of children; a stark 1970s staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with Oberon spinning plates; and a nine-hour presentation of the epic Sanskrit poem The Mahabharata that was performed, among other pit stops in a four-year world tour, in a quarry in the Adelaide Hills as part of the 1988 Adelaide Festival.

Brook has won more awards and commendations than you can shake a minimal prop at: Tonys, Emmys, a CBE, the French Legion of Honour. But all that is in the past. What means most to Brook is the present.

“I’m always very grateful when something goes well,” he says good-naturedly, “but I have never had the wish to hold on to a single object, or even a single person. I love tearing things up and, naturally, living in the moment means bringing all one can to the moment — and when the moment is gone, it is gone.”

In October, Brook’s acclaimed production The Suit will travel to Adelaide’s State Theatre Company for an exclusive season. Based on a 50s novella by South African writer and intellectual dissident Can Themba, it’s a township-set fable that — with the aid of a few chairs and metal clothes racks — tells of one man’s reaction on finding his wife in bed with another man, who leaves his suit behind as he flees. Around this is a bigger story of betrayal, retribution and forgiveness in a society in torment.

The husband’s revenge is clever and cruel: the couple will treat the lover’s suit as if it were a person, an intimate. They will eat with it, sleep with it, take it for walks; she will sing for it. Home alone, she dances with it. A one-act play that is variously a comedy, a tragedy and a musical, The Suit has moments of devastation and glimmers of grace.

“Themba was a man with the talent of Chekhov,” says the Paris-based Brook. “It’s a mystery of creation why that talent flourished in the worst conditions, under apartheid and being denied permission to publish. He died very young [aged 43] from drink but produced some remarkable short stories.

“There are so many million variations on the husband-and-wife story but The Suit has something unique. For me it is unconsciously expressing something of the pressure cooker in South Africa, of the way terrible oppression can make a big impact on one’s personal relationships.”

Brook first staged the play in French in 1999 at the Bouffes du Nord, the 19th-century tumbledown theatre behind Paris’s Gare du Nord station that was his base for more than 30 years. Titled Le Costume, it toured until 2002. Plans for a second round of touring in English, its original language, were made. It wasn’t until Brook was auditioning new cast members in the US with his long-time collaborator Marie-Helene Estienne, that they mutually decided it wasn’t ready. It wasn’t mature enough. The timing wasn’t right.

Given Brook’s work is built on the notion that nothing is fixed, that everything is reworkable, rediscoverable and growing, this wasn’t such a big deal. The work lay dormant for 10 years.

It was Estienne who suggested they pick it again. In 2011 she was touring South America with their staging of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, which featured composer Franck Krawczyk as sole accompanist, and she found herself profoundly moved by the so-called Chilean winter — the explosion of violence between Chilean riot police and largely peaceful student protesters.

“There was a heritage of similar regimes in Syria, Egypt, Yemen,” says Brook. “Given my own political background with Vietnam and US [pronounced “us”, his 1966 anti-Vietnam War protest play with the Royal Shakespeare Company], I was struck by making this [The Suit] about us.

“We decided intuitively to broaden it out, so that somehow you feel the presence of apartheid was not just a local thing but part of the apartheid disease through all the history of humanity.”

The French version had recorded music. The Suit has a live instrumental trio accompanying the four actors, with the musicians involved in the action. Krawczyk’s score takes in Bach, Billie Holiday and Schubert as well as South African township jazz: “The music corresponds with the emotions in the story, takes the situations into something more widespread.”

After premiering at the Bouffes du Nord in 2012, The Suit made its British debut at the Young Vic, where Brook’s latest play, The Valley of Astonishment — the last in a trilogy of plays about the human brain that Brook and Estienne have developed across more than 20 years — opened the evening before our interview. I had spotted Brook in the crowd after I’d taken my seat in the auditorium and read the photocopied note declaring the company’s solidarity with the “intermittents”, France’s artists and technicians protesting their right to maintain the unemployment relief known as the regime d’intermittence. Alongside him was his wife Natasha Parry, 84, who back in 1972 was part of the diverse international troupe (including Helen Mirren) that joined Brook on a research trek through Africa, giving performances in small villages.

“I’ve never been someone who feels nervous on an opening night,” he says. “Last night there could have been tension but the cast were completely open. The actor has to make the audience at first and then the audience begin to make the actor until it becomes a two-way current, and that was there last night.”

Born in London to Jewish Latvian parents, both scientists and libertarians (their name, Bryk, was anglicised by a British immigration officer), Brook was seven when he staged a production of Hamlet for family, with himself in all the roles.

He’d wanted to be a conductor (“When I was 12 I stood in front of an old gramophone waving a pencil”) but discovered that by “collaborating” (“directing is such an authoritarian word”) he could bring together all his beloved arts.

After graduating from Oxford University he looked around at the cosy, anodyne plays of the day and vowed to shake things up. An early production of Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov with Alec Guinness began with a loud pistol being fired at the audience. A production stint at the Royal Opera House included a controversial 1949 staging of Strauss’s Salome with hallucinatory sets by Salvador Dali. He did Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon before deciding to do away with the proscenium arch.

By the time he published The Empty Space he had evolved into a theatrical maverick, changing the cultural climate in Britain with his feverish invention, multiracial casts, and by tearing down Shakespeare to his human essence.

In 1971 he decamped to Paris, to the Bouffes du Nord: “Britain then was too insular and hidebound, which thankfully is no longer the case. France seemed to be a place where there was no cultural barrier to people of different cultures. Artists like Chagall, Giacometti and Mondrian were welcomed in Paris; I felt there was an opening for theatre.”

Though Brook officially retired from the Bouffes du Nord in 2008, he continues to do productions with his small team. The theatre — with its crumbling plasterwork and earthy red interior — is, he says, “the real basic implement for our work”.

It was at the Bouffes that Brook workshopped and debuted a series of plays that reflect his long fascination with Africa: 2005’s Tierno Bokar, about the eponymous Malian Sufi and his message of religious tolerance, based on a book by Malian writer Amadou Hampate Ba, who met Brook in the 1950s.

His French-language production of the searing Sizwi Banze is Dead, co-written by actors Winston Ntshona and John Kani and playwright Athol Fugard, toured Australia in 2007; 11 and 12 — a meditation on fundamentalism, personal sacrifice and tribal divisions in French colonial West Africa, also from a book by Hampate Ba — was performed at the 2010 Sydney Festival.

Then there is The Suit, which — along with Sizwe Banzi is Dead and Fugard’s The Island — stems from Brook’s long connection to the Market Theatre in Johannesburg and its former director, playwright Barney Simon.

“[In 1976] Barney started a theatre in the middle of a market because he brilliantly and courageously realised it was one of the few places the races could mix under apartheid,” says Brook. “After we did a South African season at the Bouffes we heard that [in 1993] the Market was doing a play called The Suit, so we got a copy and adapted it into French. Now we have this version that is going to Australia, with the most wonderful cast.”

The best actors, he says, are those who have managed to work through hang-ups such as vanity and exhibitionism to become increasingly transparent: “The real thing in performance is the moment when you are no longer trying to control what is going on and it is flowing through you, like a miniature of the ideal moment in life. When there is no longer any question that you are part of life.”

Despite the criticisms that are sometimes levelled at Brook — that his methods have become cliched; that he could put on a play about paint drying and still be proclaimed a genius — there is something inherently spiritual in his calm wisdom and lifelong search for truth.

Brook’s personal interest in Sufism, an esoteric and peace-loving branch of Islam, has been little written about, even if his 1979 film Meetings with Remarkable Men underscored his devotion to Greek-Armenian mystic GI Gurdjieff, a new-world prophet who was himself strongly influenced by Sufism. Brook found a hero, too, in Tierno Bokar, a peacemaker he has likened to Martin Luther King.

“The truer and deeper the inner experience the less you want to cheapen it [by discussing it],” he says when I press him. “But I’ve always thought that the only way to bring together Christians, Buddhists, Muslims and Orthodox Jews is to do a little helicopter tour for the Pope, the rabbi and the archimandrite and so on.”

He pauses, smiles. “You would start with Chartres Cathedral in France, then go to the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, then to one of the great carved Buddhas. Then you could go to Jerusalem and stay there. And the people you were taking couldn’t fail to recognise that what vibrates inside them, in each of those places, are the same experiences.”

Ninety years old next March, with only his body slowing him down, Brook now seems more philosopher than director, more master than maverick. He remains, however, a magician, who for all his back-to-basics sets is able to make an audience believe that a clothes rack is a window, that a few bamboo poles are a forest, that a glass of water contains an ocean.

“No play in the whole of history has ever changed a policy of the world,” he says, his blue eyes crinkling at the corners. “But if it brings a drop of something more positive, if there’s a quality of thought and feeling that touches even one person who is there, then it is worthwhile.”

The Suit opens in Adelaide on October 1.