Peter and the Starcatcher’s hirsute pirates are schooled in Victorian girlpower

Broadway writer Rick Elice talks about his Peter Pan origin story Peter and the Starcatcher, surviving grief and how staging a musical can resemble a military operation.

Four-time Tony Award nominee Rick Elice knows the Broadway business inside-out. He went to his first Broadway show when he was three and started his career in the 1980s at an entertainment advertising agency. There, he devised marketing campaigns for more than 300 Broadway shows, including the hugely lucrative The Lion King and A Chorus Line, before becoming a creative consultant to Walt Disney Studios.

In the 2000s, the Yale drama school graduate segued into writing plays and musical scripts – in 2004, he co-wrote (with Marshall Brickman) the book for Jersey Boys, a jukebox musical about legendary American band The Four Seasons which went on to tour the world and garner Tony, Grammy and Olivier awards. He also co-wrote the screenplay for the 2014 film adaptation, which was directed by Clint Eastwood, and the book for The Addams Family musical.

New York-born and raised, Elice created the script for the Peter Pan origin story, Peter and the Starcatcher, adapted from a best-selling children’s novel by Dave Barry and Ridley Pearson. This musical play, which is aimed at adults and children, opened on Broadway in 2012 and snaffled five Tony Awards. An inventive, gleefully punny tale of magic, hirsute pirates, lost orphans and Victorian girl power, the play has been rebooted by Australia’s Dead Puppet Society and is touring nationally.

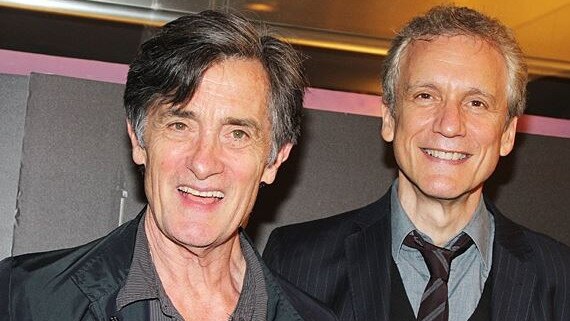

Poignantly, the original American production was co-directed by Roger Rees, Elice’s late husband and sometime collaborator, who died of brain cancer in 2015. In an interview with Review conducted in New York, sixty-something Elice talks about the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, being in the “shitty club” of widowers and his latest Broadway hit, which fuses daredevil circus feats with drama.

How did the best-selling children’s novel Peter and the Starcatchers become an award-winning Broadway play that is essentially a Peter Pan prequel?

RICK ELICE: I thought it would be fun to make it an origin story, about how some boy, an actual nameless boy, becomes the boy who would not grow up. How did that happen? Where did the notion of Captain Hook having a hook instead of a hand come from? Where did this little fairy creature, Tinkerbell, flying around, come from?

Why have you turned Peter into a feral, horribly abused orphan?

It’s hard to remove that Dickensian influence of the Oliver Twist character, the orphan who has nothing and nobody, and he is in stark contrast, even to the other orphan boys. This boy has been in a garret somewhere, looking up at the sky through broken wooden slats, and if he shifts his weight, maybe he can see a star. He’s never breathed fresh air.

What inspired you to make the play’s young heroine, Molly, an aspirational swimmer and a born leader in an era when girls were supposed to be followers? When I was growing up, I was an avid reader. I read (about) the character of Jo March in Little Women; the character of Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. I discovered that female characters can be empowered and not just an accessory to the male character of the story. Molly is the daughter of a highborn person, and she’s very bright. She is motherless and she just knows everything. As a result, she has no friends at school. So these two friendless kids meet each other and bond. Molly is also a fantastic swimmer in that way that British Victorian women always aspired to be.

Peter and the Starcatcher won five Tony Awards. What drew you to Brisbane’s Dead Puppet Society’s new vision for the play, including the addition of 90 puppets?

It’s thrilling, really. When we first did the play (in the US) our mantra was, “Let’s do the steampunk version of it as if we had no resources whatsoever,” because we actually had no resources. We did it in a closet and there was a rope, bucket, mister and a ladder, and that was all we used for the first production. So (Dead Puppet Society) director David Morton and (creative producer) Nick Paine coming along … in a way, I feel like this is an origin production for the play. The actors characterise the human characters, flora, fauna and sea life. They will be supported in this new production by these very brilliant puppet inventions of crocodiles, flamingoes, sea creatures and mermaids.

First staged in 2009, Peter and the Starcatcher is still among North America’s most produced plays. What makes it so enduring?

When it played on Broadway, it became a hot little hit. It won a bunch of Tony Awards, and was nominated for many other awards. Plays about Peter Pan usually don’t receive that sort of serious attention. Every year I think there’s 200 productions of this thing across America. It’s wildly popular because it has lots of roles and because it’s not about anything that makes people a little bit nervous. There’s no touchy subjects. It’s a beautiful story about telling stories and friendship.

Did you set out to appeal to adults as well as kids through the play’s sly humour?

Absolutely, although there’s nothing in here that would be inappropriate for kids. (For the adaptation) I thought, “I’m only going to use the things that JM Barrie used (in his Peter Pan play)”. He used high comedy and low comedy. He used alliteration, puns, anachronism and verse. He had little sea shanties. Also, I wanted to connect what he wrote with what (novelists) Dave Barry and Ridley Pearson wrote 100 years later.

Turning to your broader career, including as the co-writer of the Jersey Boys musical and film …

Do I have a broader career? Gee, Rosemary, nobody has ever said that before. I may just have to keep you here!

You have said you couldn’t have written the book for your recent hit Broadway musical, Water for Elephants – an adapted circus tale set during the Great Depression – had it not been for Peter and the Starcatcher. Why?

The poor theatre is a storytelling conceit; it should feel as though the play has been found in a drawer, and now it’s going to be done with as little as possible, in terms of objects. And so, a rope can become the ocean. It can also be the mast of a ship or a doorway. And that’s very much how I approached Water for Elephants, because I wanted to lean into the idea of it being a memory story (with an elderly man looking back on the losses, loves and circus adventures that defined his life). All you see is the trunk of an elephant, until you remember how you first communicated with that elephant, and that’s when the whole creature appears (on stage). So, Water for Elephants was informed by what I learned from the process that gave us Peter and the Star Catcher.

When you were adapting Sara Gruen’s 2006 novel, Water for Elephants, and Starcatcher for the stage, was there any tension with the authors over your changes?

Maybe this is a reflection of real talent, because it happened with (Starcatcher authors Barry and Pearson) and with Sara Gruen: I think the great authors are very generous about their stuff. OK, a play is going to be different. Obviously, you can’t do the whole novel because A, it would take five hours, and B, it would be just unwieldy.

For the Water For Elephants musical, you came up with a new ending. Is it true this reflected your struggle with profound grief after your husband, Welsh actor and director Roger Rees, died in 2015?

By the time I had been asked to write it, it wasn’t just a circus story to me. It was a story about loss, because I had just been widowed after 35 years. I thought, “My heart is broken, and how am I going to put one foot in front of the other?” I had been part of a couple from the time I was 23 years old, and suddenly I was almost 60, and I had never been an individual person, and I didn’t know how to function in the world.

There are also striking parallels with how you were feeling and how this musical begins?

I thought, “Well, this is how the boy (protagonist Jacob) begins the story”. He goes off to school one day and comes home that night, and his parents are gone. That house is repossessed by the bank. He’s got no life. This wave of awfulness has crashed over him, and he thinks he’s going to throw himself in front of a train. At the last minute, because it happens to be a circus train, it changes the trajectory of his life.

Why do you say that being a widow or widower – the surviving spouse or partner – puts you in a “shitty club”?

There’s something about grieving, bereavement that is so isolating, because many well-meaning people, loving people, say, “Oh, I can’t imagine what you’re going through’’. They actually can’t, because they haven’t gone through it. But there are people who have – me, I’m in that shitty club – and I wanted the (old man) character at the end of Water For Elephants to say, “being the survivor stinks’’. And I wanted to see heads nodding in the audience, of people who have felt alone. Like with Peter and the Star Catcher, it’s that moment where the play connects with the audience.

Did Water for Elephants’ seven 2024 Tony Award nods, including one for best book of a musical, lift your spirits?

It’s been good for my heart, sure. I don’t go out on dates, I haven’t coupled up with somebody else. It’s just I had many, many years with somebody who was terrific, a very good person, loving and kind and sweet, and I tried to coast on that. It took us eight years from the time we got started (on Elephants), to the time we opened up Broadway. Covid didn’t help, there were three years where we just sort of stalled and rewrote and rewrote.

The courage and skill of the acrobats and aerialists in Water for Elephants is astounding, with one circus artist swinging out over the audience while embodying the soul of a horse. You liken these aspects of the show to a military operation?

We weren’t interested in circus for circus’s sake. We wanted the acrobatics and the aerial stuff to serve the storytelling. Co-choreographer Shana Carroll brought down these two people from her Montreal circus company and five (more) people. Every night before the performance, they run through everything they might have to do so they can replace each other (if someone is sick or injured). And that is the real genius behind Shana Carroll and Jessica Stone, our director – it is really like co-ordinating a battle field.

What drove you to write a memoir about your late husband, Roger, who won Olivier and Tony awards for playing the lead role in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s landmark production, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby? Did the memoir help resolve your grief?

It didn’t. It wasn’t therapeutic, but I didn’t write it to be therapy. I wrote Finding Roger, An Improbably Theatrical Love Story, because Roger was a Brit. He wasn’t, certainly, among the most famous actors in the world. He did some telly here in the States (West Wing; Cheers) and became well known, and he was at the RSC for 20 years, and beloved over there. But 90 per cent of him was just this person that nobody really knew about. So I thought I would like people to know a little bit more about the part of him nobody saw but me. As it turned out, no one from his family was still alive, so it was really up to me.

You were shocked to find Roger, who co-directed the original Starcatcher, was trending when he died?

The day after he died, my nephew called me and said, “Roger’s trending’’. I didn’t even know what that meant. Of all the things for people to think about all over the world, there was Roger’s name, like, in the cloud big, like, bigger than Obama, who was the president at the time.

You have been working in the theatre for four decades. How important is that work to you these days?

Do I wish that work wasn’t everything to me? Sure, nobody ever on their deathbed said, “Gee, I wish I’d spent more time at the office’’, but the work I do feels a bit different. Every time you do a project, they (the creative team) become a second family. Jersey Boys was like that. I still have every day, 20 emails from people who’ve been in the show or are doing it somewhere. I still get together with the cast members and the people who made the show. We became a family, so that’s what sustains me.

Peter and the Starcatcher opens in Adelaide from January 9; Sydney from January 31; and Brisbane from March 14.