Paul Schrader: First Reformed with Ethan Hawke may be his final film

American filmmaker Paul Schrader may have directed his last work — and he says it’s such a good one, that’s fine by him.

Paul Schrader talks about his remarkable new film, First Reformed, as “slow cinema”, a term that can’t begin to convey its quiet, unsettling power. The film stars Ethan Hawke as a priest in the grip of crisis: spiritual, physical, emotional. It’s a performance Hawke seems to have been born to give, and it also looks like a distillation of so many films Schrader has made: it might be austere, withholding, but it’s also quietly, almost unbearably intense.

“The idea of a slow movie is almost like a pressure cooker,” Schrader says. “If you can get the viewer into a kind of waiting mode, they’re much more receptive. But it’s tricky and instinctual. When you’re withholding things that people expect, they either come towards you, and you get control of them, or they give up and leave. And that’s part of the challenge.

“Before I became a filmmaker I wrote a book on spiritual cinema, but I never thought I would make that kind of film, it wasn’t me.’’

A conversation with filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski was the trigger. “It was really a kind of intellectual decision, and once I’d made the decision intellectually, the emotions came.”

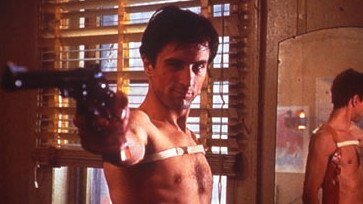

Schrader’s strict religious upbringing meant that he didn’t see a film until he was 17. When he embraced cinema, first as a critic then as a filmmaker, it was with a vengeance. He wrote four films directed by Martin Scorsese, including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Last Temptation Of Christ; and has directed more than a score of titles since the 1970s, including Blue Collar, American Gigolo, Patty Hearst, The Comfort Of Strangers, Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters, Affliction and The Canyons — many of which he has also written.

Schrader talks about favourite films that have marked First Reformed in various ways: things that he has borrowed include a central character from Robert Bresson’s Diary Of A Country Priest and a levitation scene from Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror. Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light is an influence, so is Carl Dreyer’s Ordet, all works he describes as having “a spiritual style and import”.

But, he adds: “I didn’t realise that what was tying them all together was Taxi Driver. I was in the editing room and the editor said to me: ‘You know there’s a lot of Taxi Driver in this movie.’

“And I said: ‘I know there’s some, I put it in there.’ And he said: ‘No, there’s not some, there’s a lot.’ And then I realised the whole engine of the film is an engine of repression.”

In First Reformed, Hawke’s character, Reverend Ernst Toller, is in charge of a historic place of worship in upstate New York, sparsely attended, visited more by tourists than worshippers. The congregations flock to the institution down the road, the expansive Abundant Life church. Toller meets a new parishioner, Mary (Amanda Seyfried), who asks him to talk to her husband, Michael (Philip Ettinger), to see if he can help him.

Michael is an environmental activist who’s deeply pessimistic about the future. Mary is pregnant, and Michael wonders if they are doing the right thing, bringing a child into the world. Meeting Michael and Mary marks a significant change for Toller, who carries a burden of grief and uncertainty. Toller, says Schrader, “has what Kierkegaard called ‘the sickness unto death, despair’.” Meeting Michael heightens this, setting in train the events that build, inexorably, to a conclusion that Schrader has left deliberately ambiguous.

“Over the years, people have postulated that the ending of Taxi Driver was a dream. And even though it wasn’t intended to be, I’ve always said, ‘if you want to have that interpretation, I won’t argue with you’.” With First Reformed, he wanted to “build it right in” to ensure that various interpretations were valid. He’d screen the film and ask audiences what they made of the ending: if too many went one way or the other, “I’d shift it ever so slightly”.

One thing he’s certain about, however, is that we have a right to feel despair about the state of the environment. “I think anyone who doesn’t feel despair hasn’t been paying attention.

“As Ethan’s character says: ‘Man has always woken up in the night with a feeling of nothingness.’ But now it feels different. Maybe that question, ‘does human life have meaning?’, maybe it’s not theoretical any more. Is it one we’re going to live to see the answer to?”

Hawke brings a commitment and fierce, undemonstrative anguish to the role. “He is a spiritual person,” Schrader says. “He had been to the retreat at Gethsemane which is where Thomas Merton” — the Trappist monk who is one of Schrader’s and Toller’s touchstones — “used to go. And his former father-in-law, Robert Thurman, is a Buddhist scholar.

“But he himself is a little bit goofy, a bit of a loosey-goosey kind of guy. And I said to him: ‘Whenever you feel this tendency to entertain, to be accessible, just pull it back in. This is a totally recessive performance.’ ”

Hawke took this injunction to heart. “He was able to pull that off very nicely. In fact there’s only one time in the film, when his voice cracked at the end”, in a scene with Abundant Life’s Reverend Joel Jeffers (Cedric Antonio Kyles). “And we did the shot and he said to me: ‘I promised I wouldn’t get emotional but I just felt I would try it on that line, but we can do it again, and I’ll do it the other way.’

“And I said: ‘No, I think you’re right, I think you found the moment to break the rule. Let’s go back and do it the same way.’ ’’

There will always be that moment, Schrader says — it’s a matter of finding the right one. “If you have a rule, ‘we don’t move the camera’, at some point you have to break the rule to remind the audience of the rule.”

In First Reformed, Schrader is quick to say that he doesn’t suggest that one of the churches is better than another, no matter how different they seem to be. “One is the Christianity of eternal examination, and one is the Christianity of praise.” Abundant Life and Toller’s church are both supported by a major donor, Ed Balq (Michael Gaston), who exercises power through philanthropy and pressure.

Schrader has seen this in action. He talks about coming from Grand Rapids, Michigan, where Amway founders Jay Van Andel and Richard DeVos, religious conservatives and “two of the most powerful supporters of right-wing causes in America, have rebuilt that entire town. And they gave a huge amount of money to the college, the high school, the arts society, they built the auditorium. It’s like the Koch brothers” — billionaires Ed and David — “support the New York City Ballet. If you want to have a ballet, you can’t really say no to the Koch brothers. It’s a dilemma.”

In the film, “of course these men, who are the polluters, know that perfectly well”. He compares this to the medieval practice of “buying indulgences in church”, the notion that it was possible to purchase an exemption from punishment for certain sins.

When casting the actors who plays religious characters, you have to choose carefully, he says. “People can feel in their bones when you’re being condescending. As someone who was raised in the church and was a product of the Christian school system through college, I know exactly how these people act and think, and I can imagine how difficult [it would be] for an outsider to come and say, ‘let’s cast him’.

“I remember when I was casting Mishima in Tokyo, if somebody on the Japanese side would say, ‘it doesn’t feel right’, I would always defer, because you can’t think your way through those things, it’s part of your instinctual tool kit.”

When Schrader was casting the role of Mary, Seyfried was one of the actors he considered, but he was told that she was passing up a lot of roles at the time. It turned out that it was because she was pregnant: she decided to do First Reformed in part because she was interested in exploring what it would be like to bring the experience directly to the film. It had an impact on the other actors too, Schrader says. “Ethan said it was really different, in those scenes, to know that the child they’re talking about isn’t theoretical. It’s sitting there, listening.”

First Reformed is shot through with familiar religious symbols and references, but there are also more obscure ones. “It’s quite densely layered and I put things in there, you know, that only a handful of people would recognise,” Schrader says.

He’s been presenting the film to religious audiences, including staff and students at his alma mater, Calvin College. He has asked seminarians if they recognise one of the symbols in the movie, and so far, he says, only one person has recognised it. “On Toller’s desk there’s a paperweight, which I show a couple of times. It’s a picture of a woman’s palm with a hazelnut in it. And that’s the symbol of Julian of Norwich; she wrote the first book of meditations, Revelations of Divine Love. She would talk about looking at a hazelnut in her palm, until it assumed the proportions of the world. I gave the paperweight to Ethan at the wrap.”

He might have espoused slow cinema, but the film was shot very quickly. That’s the point, in a way, Schrader says. “The cost of filmmaking has dropped dramatically. I made it in 20 days and it would have been 40 days when I started, and it would have cost twice or three times as much. In the past I always felt it would have been financially irresponsible to have made one of these European art/spiritual films in America, where you don’t get subsidies from the government. But now the cost has come down so substantially, I felt that I was being responsible, that this was not a vanity investment, it was a genuine investment. And it has proved to be.”

First Reformed has been warmly received and reviewed at festivals and it has been hailed as an awards contender, particularly for Hawke’s performance. It’s going to cinemas, but not widely: people will be seeing it at home. Schrader is fine with that, he says.

“I think that it’s important for a film like this to be defined by people who saw it in a theatrical setting. But then by the time it hits VOD, enough people have heard about it — so they don’t say, ‘oh, let’s watch that Hawke movie’, they say, ‘oh it’s that slow church movie’. So by the time they’ve agreed to see it, they’ve already accepted your terms.”

If F irst Reformed is also his final work as a director, Paul Schrader is fine with that too. He has other projects in train, but knows from experience how hard it is to get things made.

“If you had to pick a last film, [this] would be a good one.”

First Reformed screens at the Golden Age Cinema, Sydney, for a short season from November 8 and will be available on DVD and digital from December 5.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout