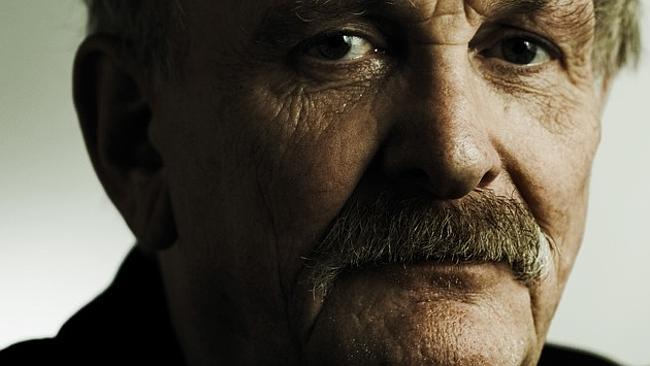

Paul Cox’s cance9r struggle conveyed in new film Force of Destiny

Paul Cox has stared death in the face, and the experience continues to enrich his highly empathetic films.

Paul Cox’s films are always personal, for which he makes no apology. He’s even receptive to the suggestion that they can be taken as a guide to his inner life. “A lot of what I do is instinct,” he says, “and I don’t reason with it. Because once you start to reason with it, it’s gone. There’s an inner voice that’s quite strong, and people will often say, ‘Of course, it’s a Paul Cox film.’ I can’t help that. It’s about my perception of the world.”

But, he argues, in what amounts to a personal manifesto, there’s also more to it than that. “You can see in all of my films that there’s an element of hope, of optimism, which isn’t me at all. But I don’t want to pull people down, the lives they lead. Isn’t life given to us to be richer in spirit, as Vincent van Gogh said? So I think that every film should make you richer in spirit and that’s a bigger thing than just my spirit or what I think about something.

“But I do use my own life as a guidance. What else do you have? That’s my way of trying to get to the truth I feel inside me. That’s what I always go for and I don’t try to fool anyone. Reality is what matters to me, reality as I perceive it.”

It’s the quest to work these ideas through on the screen that gives his films such an affecting urgency. In his documentaries, from We are All Alone My Dear (1975) to Vincent (1987) and Nijinsky: The Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky (2001), and his fiction, from Inside Looking Out (1977), Lonely Hearts (1982) and Man of Flowers (1983) to this year’s Force of Destiny , his empathy for his subjects and his characters is palpable. Most of them are stories about ordinary people dealing with everyday situations.

Force of Destiny’s protagonist is a sculptor named Robert (David Wenham), who’s firmly cast in this mould. Estranged from his wife (Jacqueline McKenzie), he’s a decent man who’s happy to lead a solitary, stress-free existence in his studio in country Victoria. He welcomes the regular visits from his beloved daughter (Hannah Fredericksen) but barely tolerates anyone else’s presence in his haven. However, when he’s diagnosed with terminal cancer and finds himself on the waiting list for a liver transplant, his comfortable world is thrown into chaos, at which point the beautiful Maya (Shahana Goswami), an angel of mercy, enters his life.

The overlap with Cox’s own reality is irresistible. In early 2009 he was in the same situation and had been given six months to live. His battle to survive is recounted in his memoir, Tales from the Cancer Ward, published after the successful transplant he received on Boxing Day of the same year, and by David Bradbury’s fine documentary, On Borrowed Time (2011), narrated by Wenham. After his operation, the beautiful Rosie Igusti, another transplant recipient, entered his life.

Nevertheless, while conceding that the film has been inspired by his own experiences, Cox gets cross when people say Force of Destiny is about him. “David and I did a Q&A at a private screening and he was asked, ‘How did it feel to play Paul Cox?’ So I grabbed the microphone and said, ‘He’s not playing Paul Cox. The film is much larger than that.’ He’s playing himself and you and every one of us: he’s playing a human being … Of course, when you’re dancing on the edge of the void as I did, and constantly thinking you’re about to slip into oblivion, that’s obviously going to rub off on the film. I went through this and it would be silly not to use it. And all of the film’s intense emotions do reflect my experiences. But it’s not just about me.”

Wenham endorses Cox’s view, stressing that his research for the role ranged wider than anything he learned directly through Cox and included projecting himself into his character’s plight. “I’m sure Paul has told you that the character in the film is not him. I’m playing Robert, not Paul, although obviously the story has been inspired by Paul’s journey. I saw him during that time, so I’m aware of what he went through. And I met other liver transplant recipients through him at the hospital, so I got to know them quite well and got a real insight into what the journey is like. I also bring what I have to the role and it was impossible to divorce myself from that situation.”

Essentially, Robert is another of Cox’s Everyman figures, no more or less flawed than the rest of us, who has been confronted with the fact he will die soon without the prescribed interventions. His reactions to the news are typical of how anyone may respond in such a situation: initial disbelief at the diagnosis; going online to check out the implications; dismay at the doctor who never looks directly at him as he delivers the prognosis; irritation at the way everybody fusses over him, especially at the constant “How are you?” refrain; disquiet at the way those around him are getting on with their lives, his interactions with them forever being interrupted by mobile phone calls.

Cox is all too aware of the physical symptoms cancer sufferers have to deal with, especially the side effects of chemotherapy. “I get very cold on my bald head,” he says, removing his beanie with a world-weary grin. “I think that the Samson story is right, that your strength comes from your hair. And it’s painful when you lose it. But then I think about what it must be like for women. It’s a horrible thing. I had two chemo procedures and you get very sick afterwards, too.”

However, rather than focusing on this aspect of his protagonist’s struggle, Cox’s attention is elsewhere. “I was more interested in the emotional side, the sense of loneliness, the longing to share your bed with someone; not for sex, because Robert’s not capable of doing anything at that point, but just to be together with someone. I think that scene with the Beniamino Gigli song that Maya puts on is enough [Una furtiva lagrima from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore]. You don’t need to go much further.

“When I first watched it back, with his head on her shoulder, I wept. It was very direct for me. I know that it’s a very old trick to put on a bit of opera, but what else can you put in there? You would never have the same intensity and depth, the glorious human emotions, without it.”

Just as it turns out to be for his character, illness has been a learning experience for Cox. “When I look at this film,” he explains, “I realise that life is so much a matter of fate rather than choice. I’ve lived with the delusion that I was the one in charge, that I have had a lot of choice, but it always turns out in the end that things just happen. And the more you come to understand that, the more choice you have in the end.”

Cox has always been one of those filmmakers who goes his own way, on his own terms. Wenham, who first worked with him on Molokai: The Story of Father Damien (1999), is one of a host of Australian actors through the years who’ve placed their trust in Cox’s artistic impulses. “Paul is somebody with a very singular vision,” he says. “He will trust his instincts and will always follow through. He will always listen to everybody, but then, contingent upon that, he will always do what he wants to do.

“When I began work on Molokai, I found it very frustrating because he was very particular, wanting me to work within very specific parameters. Sometimes it didn’t feel completely organic, so I’d try to argue the point. But Paul was always firm. So I found the best way was to give myself over to it and that turned out to be rather liberating. And I realised that he has such a specific way of working, so different to anybody else that I’ve ever worked with. And he has a specific way of shooting a sequence that not many people do any more.

“I think it’s pretty evident in this film. He loves trying to capture the drama in one shot. He doesn’t like terribly much coverage. He thinks very carefully about how he wants to compose a scene. So once you realise that you have to fit into that composition, then …”

Cox is busy planning his next project, a collaboration with playwright Daniel Keene, and he’s excited about it. “It’s called Sublime,” he reveals in a mock whisper, “and it’s all about modern art and traditional art. I’ve talked to Isabelle Huppert about it, she wants very much to do it, and we’ve got a producer in Holland. We’re in standby because of my situation, but we’ve now got half the money we need. It’s the same as it was with this film: nobody thought that I would get to the end of it. Yet I ran faster than anybody on the set, so …”

Cox is aware time is running out, as it is for all of us. But he’s determined not to waste a minute. In July 2009, almost six months after his initial diagnosis, he announced to Bradbury’s camera: “At the moment, I intend to survive. Too many things to do.” Six years later, he feels the same. “It’s extraordinary to be confronted by the ultimate, by death,” he says. “It’s not easy. And it’s happened to me quite a few times now and I’ve stubbornly hung on to life. What is that? I’m not afraid of death. But I think I’ve always been secretly in love with life.”

Force of Destiny opens the Melbourne International Film Festival on Thursday and is in general release later in the year. Cox will be interviewed by Review’s David Stratton in a MIFF session at the Wheeler Centre on August 15 at 1.30pm.