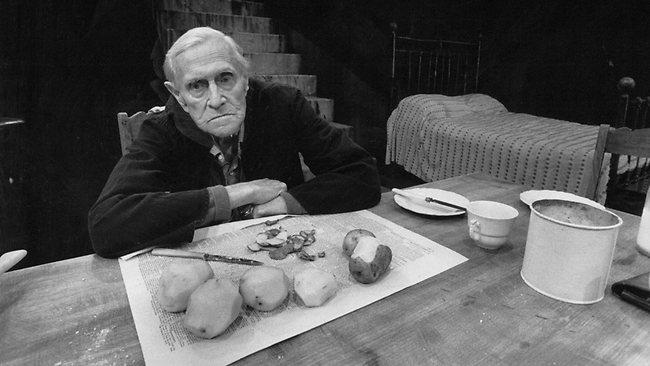

Patrick White, the outcast, returns to the fold with The Hanging Garden

PATRICK White may be barely read these days, yet the publication of his unfinished novel reaffirms his genius.

WHEN The Hanging Garden is finally published this month, four years after its existence was announced by the author's biographer, David Marr, and more than two decades after Patrick White's death, it will be cause for celebration and an occasion for pique.

Worth celebrating is the fact Random House is releasing a lost novel by our sole Nobel literary laureate and the man Marr calls the "most prodigious literary imagination in the history of this nation", in the centenary year of his birth.

And the pique? Any excitement is likely to arise from the glamour of the moment, not the contents of a novel. If White had completed The Hanging Garden instead of putting the book aside in the early 1980s to concentrate on theatre and political activism - publishing it around the time of 1979's The Twyborn Affair and 1981's autobiographical Flaws in the Glass - it would now be an unremarked companion to those titles on second-hand bookstore shelves.

Worse still, had the manuscript been shopped around today, without the benefit of the author's name attached, it may well have met the same fate as his 1973 novel The Eye of the Storm, rejected everywhere when it was submitted under the White anagram "Wraith Picket" as a hoax in 2006. So yes, The Hanging Garden's publication is a big-ticket event. But the klieg-lights illuminate a body of work cobwebbed by neglect.

It is not that White has been entirely ignored. The past quarter-century has brought many of the add-ons that come with Nobel status. A bibliography, academic monographs, Letters, a swag of translations, some satellite memoir and a biography that has been welcomed as a classic in its own right. Yet even Fred Schepisi's fine recent adaptation of The Eye of the Storm (film remains the most galvanising shock our culture can apply to a writer's corpus) feels like one more in a series of displacement activities: busywork to evade the truth that White is largely unread.

Marr makes this last point in his 2008 essay on The Hanging Garden and provides hard sales numbers to back it up. He plausibly suggests that pessimistic and puritan streaks run deep in White's work, and that this authorial high-mindedness stands as a reproach to a contemporary reading community in thrall to fashion and the cult of happiness. Doubtless he is also right to claim that White's gnarled baroque style is challenging for many readers. But there is a further reason: his close association with a particular project of cultural nationalism.

No intellectual undertaking in this country has come under more sophisticated or sustained attack in the years since White's death than that of a national canon. That there is a collection of works of enduring literary worth that constitutes a summa of who we are as a culture has been attacked, and eventually demolished. Hierarchy is embedded in the very structure of the canon, runs one powerful argument. So what looks like an uncontroversial list of "great" writers is in fact an instrument of social control. In this view canons reinforce the established order (in terms of class, race or gender) and work to restrict diversity. As poet John Kinsella wrote recently:

In using the resurrection of literary works as part of a canonical ploy to create a sense of national identity, to define the classics by which we might anchor our own vicarious and precarious identities, we run the risk of affirming the many other dubious tenets of any nationalism. Nationalism is about exclusion, about quarantine, about community in which consensus, the rights of all to have a say, are ceded to bodies of authority.

Kinsella's piece is thoughtful and properly sceptical. It also helps to explain the posthumous collapse in White's standing. As the author who, according to the Nobel judges, "introduced a new continent into literature", White's fictions were placed firmly at the centre of an emergent Australian canon. It was to works such as Voss and The Tree of Man that our "vicarious and precarious" identities were meant to be tied. Yet efforts by academics in our universities to break the canon in the name of greater inclusiveness and democracy have damaged the author who justified that canon's existence more than any other. White's reputation has never been fully extricated from the web of ideology woven around it.

There has been no active campaign against White in schools and the academy; more a grudging indifference. His fictions are still taught at secondary and tertiary levels, albeit mainly in the context of gender studies or postcolonialism, where his former canonical status is downplayed. White's fictions belong to a slender rump of "classic" texts that are kept on our curriculums, anachronistic though they may be, on the basis that they submit to narrower readings: a seam-mining of politically appropriate aspects in their work.

The irony of this situation is inescapable: White has been sacrificed on the altar of an activism that he helped bring about. On indigenous rights, censorship, immigration, nuclear power and a host of other issues White was an impassioned spokesperson for those who believed that the old Anglo-Australian order was culturally stultifying and politically backward. A disgust for materialism, racism and philistinism in Australian society pulses through his work, as does compassion for the outcast and excluded who suffer their effects. For a reminder of these truths we need only turn to the opening pages of The Hanging Garden.

The time is World War II; the place, Sydney, in all its wartime drab. Two children, bourgeois evacuees, are left in the care of a blowzy widow, Essie Bulpit (the intimations of bullshit and pulpit are intended). The girl is Eirene Sklavos, the daughter of an Australian woman and an aristocratic Greek communist, murdered in prison during the early days of the Axis occupation. The boy, Gilbert Horsfall, is English, though keen to remake himself as an Australian. His father is a senior staff officer in India, his mother was killed by a bomb in London.

Thrown together by unhappy circumstance at the end of the world, these semi-orphans at first circle each other with a wariness that suggests animals marking territory. But their carer is benignly neglectful, and her ramshackle house set in a large overgrown garden on the harbour foreshore: there is enough room for them to be alone, though paradoxically this heightens each child's sense of the other's proximity.

It would be a mistake to call this garden a paradise in the biblical sense. It is too seedy and verdant for that chaste perfection. Rather, it is a green redoubt to which the numbed and culture-shocked pair can retreat and take stock of their respective wounds. At mealtimes they are obliged to dine together and to oblige Mrs Bulpit with a measure of social normalcy. But as is so often the case in White's work, human society here is only a thin layer applied to the surface of existence: beneath it, nature does its deeper and more vital work. Before long Gilbert and Eirene are fully possessed by the terraced stands of lantana, scattered gums, looping vines, massed pittosporum and the harbour in its countless moods. At times they threaten to merge altogether with its organic profusion, its dazing light.

As they grow closer, the pair's naively sensual play shares this quality of pagan grace. It is innocent of full adult sexuality. And their relations at home have a sincerity and ease that bear little resemblance to the masks of gender and tribe they are obliged to wear at school. Presumably (we cannot know for sure, since the narrative breaks off too soon) these early experiences are binding their lives together at the very root of the self.

We have learned by now to approach posthumous publications with suspicion. Too often they are fragments dressed up as full narratives, mediocrity passed off as genius. Once in a long while, however, if an executor is working in the author's best interest, and if outside advisers and publishers are intelligent and able, then a truly deserving work may be retrieved from oblivion to reanimate our sense of wonder at what a particular writer can do. The Hanging Garden is such a book. Like the flood waters now filling Lake Eyre its publication brings life stirring back to a long-dormant oeuvre.

One important point. It may be unfinished, but The Hanging Garden is not incomplete. As Marr explains in an afterword outlining the novel's background and history, the original manuscript consists of an almost self-contained novella, probably the first of three. What remains of the larger work has its own internal narrative coherence and unfolds in prose that is polished to the deep lustre we expect from White.

In terms of structure, The Hanging Garden explores two levels of antipodean experience. The superficial, satirical, social strand describes an aggressive effort - a kind of patriotic intervention - undertaken to draw Eirene and Gilbert into the homogenous Australian mass. The headmaster of their shared primary school laughs to learn of Eirene's intermittent childhood tutoring in Racine and Goethe. Now is the time to begin a proper, practical education. The author who will describe himself as a "black" among white Australians in Flaws in the Glass here grants his young heroine dark skin and raven hair. Though her glossy plait will be chopped to a more suitable length as Eirene gradually becomes "Ireen", another adolescent schoolgirl aware that her "reffo" status must be neutralised by an active dismantling of her Greek self. Only in the pages of a clandestine diary does Eirene keep scraps of her former life.

Balanced against this is the Australian landscape, of which Essie Bulpit's garden is a microcosm. It is a space at once physical and metaphysical, incontrovertibly there yet standing outside of history or ordinary morality: a zone in which constructs of culture and nation melt away. Within its borders, Eirene and Gilbert enjoy the same brief interregnum described in novels such as Giorgio Bassani's The Garden of the Finzi-Continis or Ian McEwan's The Cement Garden: a momentary freedom, wrested from the larger shaping forces of the adult world. I used to think that the most vivid evocations of Sydney in White's writing occurred in 1970's The Vivisector, but there are passages here, seen through Eirene's eyes, just as fine:

It was a steamy morning. You had gone down early, before the others were up, through the dark garden, to the sea wall. Everything dusty, or dank, or patent-leathery about the foliage had been exorcised by an influx of slow light. In the lower garden the hibiscus trumpets were expanding, and reaching upwards into what was not their native province, their pistils bejewelled with a glittering moisture, along with the wings of big velvety butterflies. Their petals flapped through territory which normally belonged to moths and bats. The harbour had subsided this morning into a sheet of wet satin. Gulls had furled their harshness for the moment and were amiably afloat above their reflections.

What allows Eirene to slip the superficial bonds prepared for her by school and community is love. Her feelings for Gilbert are complex and one-sided, since "Gil" is able to reciprocate only in the false coin of male desire; yet they are inspired by some pure elemental force. Some of the novel's loveliest passages involve Eirene's dimly intuited sense of the mystical connection between her Greek past, with its archaic concepts of soul, and what she feels for this earthy, obtuse boy. When events conspire to suddenly separate the pair it seems that this private, half-understood passion is finished. Only at the narrative's end is the possibility of a reconnection raised.

This description perhaps makes The Hanging Garden sound too ethereal, a Symboliste's dream. In fact its exterior dialogue is pitched in Sarsaparilla-speak, that anti-poetic vernacular of White's novels and plays, while its depiction of the subtle gradations dividing Sydney's mid-century middle classes remain venomously acute. Its men and women possess the grotesque fleshliness of meat-carcasses painted by Francis Bacon, and even minor characters such as Miss Jinney Hammersley, headmistress of Eirene's north shore girls' private school, stick fast to the reader's mind:

She is still moist from her dip. Her hair has this damp frizz. Obviously Jinney doesn't give a damn for hair. She is in a skirt today, askew around her bottom. Her large gold-rimmed spectacles radiate the superior virtues of the pure-bred Anglo-Saxon upper class.

Or Aunt Ally, Eirene's only local relative, unhappily married, mired in domestic drudgery and a reluctant guardian to her sister's child after Essie Bulpit's death. She likes to live in her own car, driving round the bright Harbour bays, with her cigarettes and tissues, the boys' sports gear and the wilting vegetables she has bought cheap, keeping all else at arm's length, unless the God she doesn't believe in gives her a motor accident . . .

To read these is to appreciate once more the unvarnished exactitude White brought to his portraits. There is something freakish about his ability to trap the entire fate of an individual in a clutch of stray thoughts and character traits. Eirene is different, however. She eludes the judgment handed down on the author's minor characters, not only because she is an adolescent whose entire nature is in flux but because she is a member of White's small spiritual Elect. Eirene (and Gilbert too, in a less conscious way) is ennobled by her attentiveness to the natural world and her as-yet-unfathomed feelings for Gil.

Finally it is the multivalence of the narrative that marks The Hanging Garden as a work by White. Here is a fiercely secular editorial penned against a society where difference is a matter for fear and shame, and whose people lack a sense of heimat (that untranslatable German term for a shared sense of community and tradition, informed by place and tribal descent) and so manufacture a pale simulacrum of the Old World in the New. Yet these are daytime irritations. Beyond them there is the nocturnal inscape of mind and soul.

White's incessant questions - Is there anything beyond the physical world? May there be loving human unions beyond the carnal? - are posed here in ways as profound and subtle as anywhere else in his work. The Hanging Garden recalls us to the truth that great novels are those where the free play of the author's imagination reveals the fetters of gender or caste we wear in reality. Forget philistine Tories. The worst ideologues are those who have spent the past decades studiously ignoring White's rich bequest.

The Hanging Garden, By Patrick White, Knopf, 224 pp, $29.95 (HB)

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian. A collection of his essays on neglected Australian writers will by published by Text later this year.