Ouyang Yu’s Billy Sing: new dimensions enrich Gallipoli sniper’s saga

Though subtitled ‘a novel’, Billy Sing draws on the most celebrated Australian sniper of World War I.

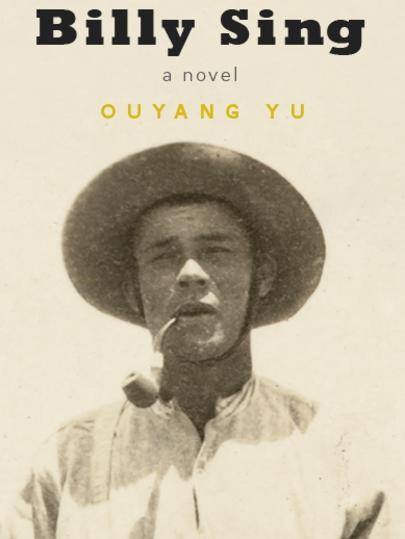

The latest work in Ouyang Yu’s remarkable literary traverse of two languages and cultures — China and the Australia to which he came in 1991 — is Billy Sing. Though subtitled ‘‘a novel’’, for the imaginative licence to come, it draws extensively and sympathetically on what is known of the most celebrated Australian sniper of World War I, in particular at Gallipoli.

Born in 1886 in rural Queensland, Sing was the son of a Chinese drover and farmer, whose father had in turn come to Australia from Shanghai, lured by gold. Sing’s mother was an Englishwoman born near Shakespeare’s home town. After enlisting in the First AIF, Sing was sent to the Dardanelles, where he was credited with killing more than 200 Turkish soldiers. He was nicknamed The Assassin and awarded the British Distinguished Conduct Medal, the citation of which read in part that ‘‘no risk was too great for him to take’’.

Sing’s story has been told previously by John Hamilton in Gallipoli Sniper (2008) and in a 2010 ABC TV miniseries, The Legend of Billy Sing, but never with the dark intensity Yu musters. Yu’s career (to stay only in Australia) includes work as a critic, editor and translator, as well as a poet and novelist. Cross-cultural engagements, usually fraught, have given a troubled energy to his writing.

In Billy Sing he imposes on himself the discipline of a notable Chinese-Australian’s given biography (for all that ‘‘large tracks of [his] life remain unrecorded’’). From there he explores notions of identity and heritage, as they can enrich and deform. The narrator lives in a world of ghosts, as his father did. We are invited to think of ourselves as being in the confidence of a ghost: ‘‘In my grave, my spirit lingers, the undead, if you believe that sort of thing, which I think you ought to.’’

Certainly Billy’s father’s voice is often present, usually with advice, never unkind: ‘‘learn the skill of ignoring people’’; ‘‘you were born of two truly incompatible languages and cultures’’. A less consoling internal voice also speaks to him: ‘‘You were wrongly born. You were born wrong.’’ Billy assimilates this counsel with stoicism rather than bitterness.

Yu portrays the complexities of the happily mixed family of which Billy is part. When his son determines to become a marksman, Billy’s father relates the story from ancient China of the archer Ji Chang, whose master taught him ‘‘to practise with his eyes … to look at the smallest things until they become bigger’’. For Billy, his gun becomes ‘‘a concentration of held breath, aligned eye and mental stillness’’. This is a choice of solitariness, apt for the military speciality that he would pursue. The amoral effect of such a disposition is that ‘‘I had the freedom of wandering in my land, Singland, with total unconcern and total abandon’’.

Nevertheless, and armoured with a bronze amulet from his father (and a backstory about Aborigines and the Palmer River gold rushes), Billy enlists and is soon thrown together with hundreds of others on a ship ‘‘like a huge floating building, or, more exactly, a floating paddock in levels’’. He is befriended by a writer who has wandered the outback for years and who will become one of Billy’s target spotters at Gallipoli. This is a cameo appearance from Ion Idriess, a prolific author of Australian tales of fact and fiction — the two not always distinguished.

For Billy, Gallipoli presents barrenness such as he has never seen before, ‘‘hills … as bare as my gun barrel’’. Idriess’s notebook describes the sniper as ‘‘a picturesque looking mankiller’’, whose story he eventually published as Lurking Death in 1942. Yu gives vivid but not extensive detail of how Sing killed, effecting ‘‘the instantaneous blooming of a flower where the head had been’’. Idriess gives him directions in ‘‘a voice as clear as crystal and low as the shrubbery’’, while ‘‘to survive the whole day, from darkness to darkness, I had to keep inhaling the smell of dry tobacco’’.

Finally, Billy is wounded. He has dialogue in delirium about war, death, memory. He wanders ‘‘like a lost cloud. All the dead were with me, too.’’

As he eases away from war, Billy meets the fair-haired Fenella, from ‘‘a family of non-blue-blooded Scots’’. She is more worried above a move to supposedly convict Australia than the number of Turks Billy admits to having killed. He tells her to expect kangaroos and kookaburras instead; he brings her home to his hero’s welcome in Prosperine, though ‘‘I was in ruins, my body riddled with wounds’’.

In a society to which such a revenant can never comfortably return, Billy finds himself among ‘‘battle-worn and battle-maimed soldiers’’, with a wife not keen on Australia and work that is dispiriting and unproductive: ‘‘Now it was my turn to survive my own failures, in the Soldier Settlement Scheme, in the gold-digging and the kangaroo-killing.’’

There is a strange trip, as if in a nightmare, to his ancestral village in China, where ‘‘everyone turned out to be a Sing’’ and his grandfather’s damning voice speaks through a medium. Then the story turns to the sad, final stages of a life no longer celebrated — and soon to be all but forgotten for a half century.

Billy Sing is compressed in a manner uncommon in Yu’s fiction, all the more sharply to focus its unsettling, powerful analysis of where a man, both strange and ordinary, came from, and how we are to reckon with the many resonances of his story.

Peter Pierce edited The Cambridge History of Australian Literature.

Billy Sing

By Ouyang Yu

Transit Lounge, 144pp, $27.95 (HB)