Outside the circle

The dispossessed are at the heart of Aravind Adiga’s new novel.

‘‘Hope is a kind of rigor. Despair is sugar.’’ This cool sliver of wisdom is dispensed late in Aravind Adiga’s new novel, Amnesty.

But when it comes, it emerges from the mind of a man in a state of extremity: living among strangers, adrift and beleaguered in a country that is not his own. His conscience is deadlocked on a moral question, to which the correct answer does not exist, yet must still be found.

The one doing the thinking here is Dhananjaya Rajaratnam. At least that is the name he was given at birth. For four years now, he has gone by the Australianised ‘‘Danny’’.

Those years have found him trapped in Sydney, as a student-visa overstayer and so an illegal immigrant. His passport has expired and he has no Medicare card. His nights are spent in a small room above a Greek-owned corner store in the inner-city suburb of Glebe; his days, working as a house cleaner.

Readers are privy to Danny’s situation from the start. We meet him in a brief, prefatory chapter as a boy growing up in the island city of Batticaloa, in the eastern province of Sri Lanka: a place with all the requisite magical realist adornments.

In the waters of its lagoons, we learn, fish sing. And on certain nights, mermaids materialise, ‘‘dripping with moonlight’’. It is a dream of home, transformed by the filter of his longing into something enchanted.

And like a dream, it is swiftly displaced by prosaic reality. Back in this world, Danny speaks English with a determined Aussie accent; makes careful notes about which rugby league teams it is correct to support. He has grown his hair out and amended it with gold streaks in a minor act of camouflage.

Each day he strides purposefully through the city, a ‘‘Turbo Model E, Super Suction vacuum cleaner’’ strapped to his back, armed with ‘‘a plastic bag, a paper roll, disposable pads, a foam spray that he used on glass, and a fire-alarm-red rubber pump that would suck the problems from any toilet bowl’’.

‘‘Sure,’’ spruiks Danny to himself, ‘‘every home keeps a vacuum and brushes and sprays in a closet somewhere, but a cleaner impresses with his autonomy’’.

We meet him, then, as a 21st-century Robinson Crusoe, washed up on an island continent with nothing but some scavenged goods, intelligence and tenacity to help him survive, though never to flourish: that possibility is forever curtailed.

For all their bluster, Danny’s thoughts do not fool us.

As we follow him from bus to train, to city streets, to house-cleaning appointments — each phase of his journey timestamped to the minute, as though the novel’s readers were gig employers keeping a contractor under surveillance — a sense grows that such entrepreneurial dash is a performance, designed to render him invisible to the rich, white, Australian world through which he moves:

His five-foot-six body looked like it had been expertly packed into itself, and even when he was doing hard physical labour his gaze was dreamy, as if he owned a farm somewhere far away. With an elegant oval jaw, and that long thin forehead’s suggestion of bookishness, he was not, except when he smiled and showed cracked teeth, an overseas threat.

Other brown-skinned people are different; they look at him rather than through him. If they are legal themselves, such people can pity him or despise him. Either way, they are a threat to be avoided.

And if those seeing him are also illegals? To seek connection is dangerous, even if the solidarity they offer or the knowledge they may share is desperately desired.

Adiga’s authorial perspective — first- and third-person narration crammed together in a space meant for one — grants us access to the monologic intensity of Danny’s interior life.

Amnesty is a novel filled with his unspoken words and overheard thought, endlessly rehearsed argument and unuttered invective. The narrator has lots to say but no one to share it with. All the words he cannot speak, dare not speak, are funnelled inward; outwardly, he simply grins and unsheathes his plunger.

There are those who know him in part, of course: the evil old Greek whose shop he lives above, who takes half his pay on each cleaning job as ‘‘middleman’’, and who only took him in because of his infinitely exploitable illegal status.

There is also the girlfriend he met online, a Vietnamese nurse who takes sincere pleasure in his company, unaware she has only been admitted into the front office of his existence.

Then there is Radha and Prakash. Danny cleaned Radha’s flat for a while. She soon reveals to him the extramarital affair she is having with a handsome, charismatic Indian-Australian. The pair come to take pleasure in Danny’s obedient complicity. They fight in his presence, then embrace, then eject the young man in the middle of his work. He waits, patiently — on a park bench, by a tree, beneath an illuminated Coke sign — until they text him to return.

Danny quit the job when his discomfort at the situation grew too strong. Yet part of him relished the companionship of two brown-skinned people who were generous towards him — interested in him, too, after their self-absorbed fashion — as well as rich and legal. Danny is understandably drawn to the devil-may-care attitude such luxuries allow.That is all in the past when — at 9.21am on the day over which this novel unfolds — Danny lets himself out of the Erskinville flat he has been cleaning, only to bump into a policeman.

A woman has been murdered, the officer explains. She had lived nearby, so police are canvassing neighbours. Radha’s flat, coincidentally, is just across the road.

Danny’s dilemma begins at the point when he realises who it is that died. Following that knowledge comes a flood of memories, each of them raising a bright, red flag.

The doctor was Radha’s lover. Their relationship had a violent edge. Could he, Danny, be the only person who knows what may have really happened? Is he obliged to inform the authorities, even if that means detention, criminal sanction and deportation?

It doesn’t help to pull this narrative lever too hard. Yes, the murder and its implications for Danny drive the remainder of the novel. But Adiga is too subtle a writer, too interested in the psychological texture of his subject — too invested in a bitterly ironic inquiry into race, law and society in the Australian context — for a standard-issue whodunit.

What the murder provides is a mechanism for compression. Danny has existed for years as a projection of the expectations and needs of those who employ him, the wealthy white citizenry of Sydney.

Now his core self needs to be retrieved, and swiftly, from somewhere deep inside, so its moral capacities may be stress-tested. It is the pain and struggle of reclamation that is the real drama here, an effort his creator has no intention of making easy.

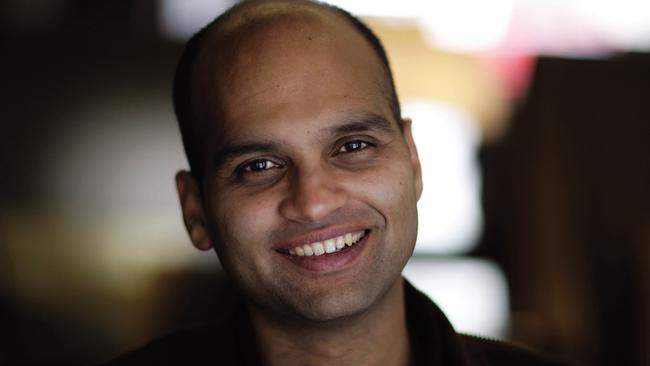

Adiga, who won the 2008 Booker Prize with his debut novel The White Tiger, is a prose-writer of considerable gifts, insight and intelligence.

He furnishes Danny with a panoply of rhetorical modes. His thoughts can shift tone from guileless idealism to cynical insight and back in the space of a line. Yet, even as the true lineaments of Danny’s character begin to clarify, we encounter a paradox: in Adiga’s hands, he also becomes an everyman, an oracle of the global dispossessed.

Adiga’s author bio states he was born in Chennai in 1974 and studied at Columbia University and Magdalen College, Oxford. It does not mention that he emigrated to Australia with his family in the early 1990s and attended James Ruse Agricultural High School in Sydney.

He knows the city; he has evidently trod down the same streets, sat on the same buses, encountered the same questioning stares, and lingered in the same 7-11s, sampling the $1 coffee that is all Danny and his kind can afford.

The exactitude and care with which the author recreates Danny’s urban experience lends an awful credence to the broader critique of Australian society that flows from it.

‘‘A circle can only have 360 degrees,’’ thinks Danny as he lies in the cramped storeroom that is his home, having spent the afternoon in a library poring over immigration law textbooks.

‘‘The law was a magic circle, and inside its protection, Australians surfed and swam and slept like children.’’

The irony of this observation emerges from the young man’s approval. The law of Australia was fair, he thinks, ‘‘perhaps it was even the best law that existed anywhere in the world’’,

But at the moment he closed his fine-smelling textbook and returned it to the shelf and walked out of the Glebe Library, it would immediately start hunting him down again — because that was its nature. Blind and fair.

Lines such as these recall that eviscerating observation by French novelist Anatole France: ‘‘The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.’’

The most confronting, most damning aspect of Danny’s small epic of homelessness may be found here. He believes in Australian law. He believes in the promise of Australian democracy. It is Australia that does not believe in him.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

Amnesty

By Avarind Adiga. Picador, 352pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout