Our movie makers: the Aussie sisters who changed film history

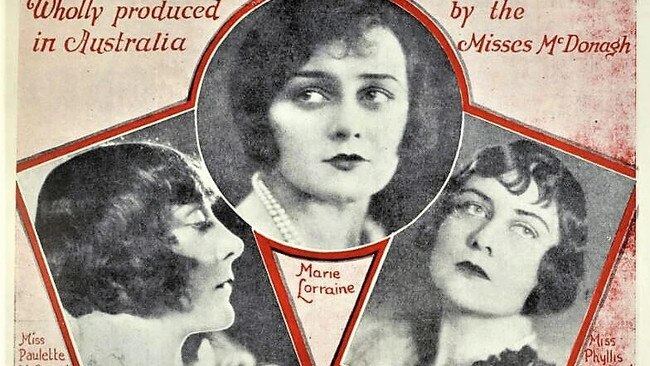

Between 1926 and 1933, the trailblazing McDonagh sisters — director Paulette; producer Phyllis; and actress Isabel under stage name Marie Lorraine — changed the course of film history.

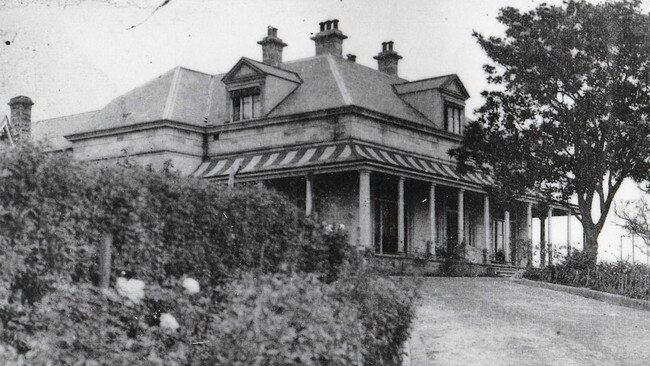

Production of Those Who Love, a Cinderella story of lost love and steep class differences, began in the middle of May 1926, and immediately the McDonagh sisters – Phyllis, Paulette and Isabel – began attracting intense interest from the press. According to Phyllis, “it was mainly doubt on the point of three inexperienced young girls succeeding where so many men had failed”. Their home Drummoyne House – still filled with their father’s collection of tapestries, Venetian mirrors, antiques, ornaments, and gold-framed oils – was the main setting for the story.

On the first day of shooting of their first film, Those Who Love, in 1926, it seemed as if all the residents of Drummoyne were standing out on Wrights Rd to take in the spectacle of a cumbersome film camera, klieg lights and reflectors, and a group of costumed actors with faces shellacked in thick make-up. In fact, the cast and crew often attracted so much public attention that they would pretend to pack up the equipment and lights so that the crowds would begin to disperse. Only once the set was cleared would they again begin shooting their scenes. Often, this pantomime would be repeated up to four or five times a day.

“We were utterly determined and took every mishap in our stride,” said Phyllis. “At the outset the three of us agreed to abolish the word ‘no’ from our vocabularies.”

The sisters wisely hired cameraman Jack Fletcher, who had previously worked in Hollywood at Paramount Studios.

For a dockside cabaret scene, supposedly set in a maritime workers’ watering hole, Phyllis was unable to find the right venue, so she designed and built a set in a Bondi Junction studio run by Australasian Films, one that could reveal the emotional and psychological truth of the hard-luck characters. Exteriors included the suburb of Rose Bay, Mort’s Dock, Prince Alfred Hospital, and the Italianate mansion, Rothesay, in Bellevue Hill.

Another landmark exterior scene was shot at Tamarama Beach. By the mid-1920s, sunbathing and surfing were becoming as popular with the Australian public as rollerskating and movie-watching. But at the time, most Australian beachgoers remained clothed as they cavorted on the shore, while the more faint-hearted sheltered beneath trees and wide umbrellas. During the shooting of Those Who Love, however, the McDonagh sisters boldly broke with this Victorian tradition by dressing the cast in modern bathers. Bébe Dorée, Barry Manton’s beautiful yet frivolous girlfriend, wears a scant swimming costume with a court-jester design and dances a spirited Charleston across the sand to the music blaring from a nearby gramophone. Her friends are delighted and soon jump up and join in. No other cinematic image so encapsulates the wild, bohemian hedonism of the jazz age in Australia.

Paulette would rehearse the actors mercilessly: their actions, their facial expressions, their eye movements, their gaze, their soundless dialogue, the latter of which would be repeated on a title card. Not a moment could be improvised, or a gesture reinterpreted.

Paulette credited her ability to direct actors from closely watching Hollywood films, noting how much more subtle and underplayed the action was compared with the histrionics of stage acting: “... when I got them they started to act their heads off. And they were so hostile, they wouldn’t take any notice of me. So I said, ‘All right, I don’t want that. You’re going to do it this way’.” When the actors refused to tone down their performances, Paulette merely shot the overly dramatic acting, had the film developed, and the following day showed the actors the rushes: “... and they were shocked. There they were, jumping and leaping. After that, they took every bit of direction I gave them”. Paulette became an advocate of what Alfred Hitchcock would later call “negative acting”: the ability to express and communicate emotion by doing virtually nothing. As the master of suspense proclaimed, “the best screen actor is the man who can do nothing extremely well”.

Brothers John and Grant acted small parts in Those Who Love, and John, who by this time had dropped out of medical school, often assisted as a sundry crew member.

Paulette never lit sets and scenes herself but rather told Jack Fletcher the effects she wanted to create, and he would make the adjustments according to her brief. But the harsh lights required to illuminate the set caused problems for the cast and crew.

“After a day of shooting your eyes were raw and watery and you couldn’t see much at all – like someone had thrown pepper into them,” said Phyllis. “Not long after shooting began we all came down with klieg eyes. We just had to lie low for a couple of days, which meant a complete hold-up with the shooting schedule.”

But even greater challenges lay ahead. Once they’d all recovered from klieg eyes, cameraman Jack Fletcher came down with a virulent strain of influenza. “The poor man was in a terrible way,” related Phyllis, “shivering and sweating, and as the day wore on Paulette and I literally held him up at the camera to get through.”

The exhausted sisters put him to bed in Drummoyne House and alternated nursing shifts, sitting up with him all night and ministering hot lemon drinks and Aspro. The following morning, groggy and weak, reliable Fletcher was back behind the camera, cranking the handle.

Another setback, however, was about to beleaguer them. “One morning we had to shoot a hospital sequence,” Phyllis observed. “The walls of the bedroom we’d adapted were reflecting too much light. Every single person on the film worked like demons repainting the whole room in their lunch hour.”

One day, around dusk, the council rang to inform the sisters that the suburb of Drummoyne had been plunged into darkness because their klieg lights were using up all the electricity. The sisters were amused by the unintentional mishap, and their tolerant neighbours did not complain.

The final scene during the shoot of Those Who Love was filmed in the Australasian studio in Bondi Junction and was one of the few scenes that Paulette shot out of sequence. It was the underworld cabaret scene during which the male lead, Barry Manton, first encounters the beautiful yet exploited Lola Quayle. The scene also incorporated 70 extras, costumed in the Apache style of Parisian gangsters, men wearing peaked caps, striped shirts and baggy pants, and women garbed in loose blouses and wide skirts, who “danced and made merry to the strains of a three-piece slapstick orchestra”. One myopic film critic would later complain that Sydney did not contain such “doubtful public resorts”, obviously not realising that the sisters were deliberately trying to create a universal story in a non-specific setting that could be applied to virtually any Western city in the world. Those Who Love and all their subsequent films would trenchantly avoid recognisable Australian settings, characters, and dialogue.

For centuries, beautiful and talented women such as Isabel have been cast in acting roles, and for almost just as long, others like industrious Phyllis have worked behind the scenes. But Paulette’s role as a female director was comparatively unusual – in Australia or anywhere else in the world – and people would frequently ask her what it was like to direct a film.

“At first it is something of a strain,” she admitted. “The nervous tension and responsibility are tremendous. But afterwards, there is no real feeling at all. Soon, it is possible to make decisions and advise quite coldly and deliberately. Sleep and the thought of food become almost impossible when actually on the job. At the end of the day we are all physically exhausted. But tiredness, somehow cannot reach you. Always there is the knowledge of something fresh to create on the morrow. The thought has an amazing and stimulating effect.”

According to the McDonaghs, the main requisite in making a film is ordinary practical common sense. Each night, after shooting, the sisters and crew would watch the rushes of that day and felt intuitively that they had a good film. At the end of the production schedule, they were also proud of the fact they were able to shoot Those Who Love in only four weeks.

On September 16, the McDonaghs prepared for the premiere of the film. For the occasion, they booked the Prince Edward Theatre and invited 200 guests from Sydney society and the Australian film industry to attend the first screening.

“We sat in the dress circle, side by side, so nervous we couldn’t breathe,” said Phyllis. “Then we relaxed a bit, reassured by that quiet which always settles in a theatre when the audience is being held. Halfway through, Paulette nudged me and whispered, ‘Look at the governor’. He was sitting fairly close by. We saw him hold a handkerchief to his eyes.”

Accompanying Those Who Love at its premiere was the famous American organist Eddie Horton, dubbed “the Wizard of the Wurlitzer”, who chose to play, at crucial moments of the film, the tear-jerking, popular song of the day, “Always”, written the year before by Irving Berlin. As the end credits of Those Who Love began to roll, the sisters were greeted with thunderous applause and a standing ovation. Their excitement and relief were palpable. That night, they rushed out to buy the late edition of the Sun newspaper and glimpsed the headline: “The Best Film Made in Australia That I Have Seen”.

Later that week, the positive reviews continued to roll in: “... excellently produced, both photographically, and from the point of view of artistic presentation”; “... a wonderful triumph ...”; “... a picture decidedly above the average ... well acted, well produced, and well presented. Story, acting, and photography give it a place which no other Australian production has beaten.” Other press reports were equally ecstatic about the quality and depth of this new Australian film, comparing it favourably with the best of any Hollywood effort.

This is an edited extract from Those Dashing McDonagh Sisters: Australia’s first female filmmaking team, by Mandy Sayer, published by New South.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout