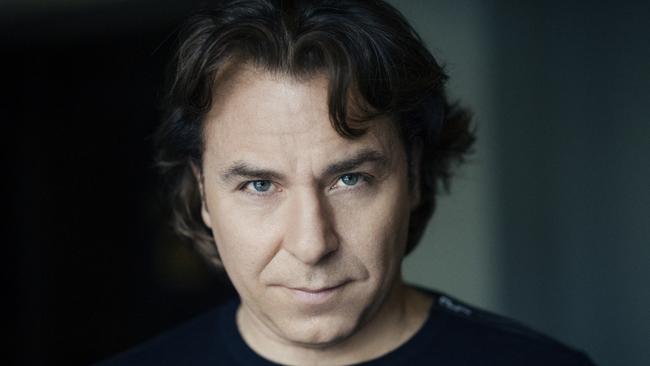

Opera star Roberto Alagna talks Aida, love and loss before local shows

Roberto Alagna’s career has scaled great heights, and some terrible lows, but the French tenor finds comfort in opera.

In December 2006, a few minutes into Franco Zeffirelli’s new production of Verdi’s Aida at La Scala in Milan, the celebrated Franco-Sicilian tenor Roberto Alagna stormed off the stage. His opening aria, Celesta Aida, had been met with scattered boos and derisive whistles from the traditionalist loggionisti in the upper balcony. So Alagna gave a half-hearted military salute and made an abrupt and unscheduled stage-right exit.

The orchestra played on. Alagna’s co-star Ildiko Komlosi gamely began what was meant to be a duet, addressing it to no one in particular: “Di quale nobil fierezza ti balena il volto! (What noble courage shines in your face!)” In a matter of moments, Alagna’s understudy, Antonello Palombi, found himself thrust on to the palatial set in jeans. Naturally, the whole agonising slow-motion car crash of it is viewable on YouTube.

Alagna’s walk-off caused shock waves in the opera community. The New York Times called it a “bravura performance” in the “history of operatic hissy fits”. “His behaviour has created a rift between the artist and the audience and there is no possibility of repairing this relationship,” a La Scala spokesman said in a statement. Zeffirelli himself said, “A professional should never behave in this way.”

I meet Alagna 10 years later, in his dressing room at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, ahead of his debut Australian performances this month. It seems lately you can hardly drag him off the stage. Earlier in the year he played the cuckolded clown Canio in Pagliacci; he signed on to replace an ill performer in Manon Lescaut a little more than two weeks before opening night; and rehearsals for Madama Butterfly begin tomorrow.

“When I have challenges, I try to do my best,” he says.

The building is still vibrating from the thunderous closing chords of Manon Lescaut. Alagna is out of his costume and make-up, wearing jeans and a black cardigan with his bare, barrel chest on display. His rudimentary dressing room is tucked away in the backstage corridors, with just a couple of mirrors and a piano, and city traffic audible through a small window.

It’s difficult to reconcile Alagna’s reputation as a prima donna and, as La Scala’s artistic director put it in 2006, his “obvious lack of respect for the audience and the theatre”, with the warmth-exuding man who holds his hand over his heart during the evening’s curtain call. “I’m very happy because … I don’t know, it was a wonderful night. I love this music. I love this character. I love the cast. I love to sing with her [Alagna’s co-star Kristine Opolais]. I love the Met. I love the people here. I love everything.”

The La Scala walkout was undoubtedly the low point in a performing career filled with highs. In 30 years, the muscular-voiced tenor has performed more than 60 roles, including in two contemporary operas composed especially for him, at the world’s greatest opera festivals and in the world’s greatest opera houses.

Like Placido Domingo before him, Alagna has lent his Neapolitan tones to several crossover and compilation records, with titles such as Tenor and Viva Opera!, that have sold in the millions. His 2006 Deutsche Grammophon release C’est Magnifique! featured French standards, a couple of Cole Porter numbers and a duet with Jean Reno on I Love Paris. There has been a Christmas album, too. (Later that night, leaving via the stage door, I run into a small mob of waiting Alagna fangirls.)

It’s surprising, then, to discover that for many years Alagna despaired that his voice didn’t live up to the sound he heard in his head. “Maybe it was the sound of perfection,” he says. “For many, many years I fought for that sound. I would break my CDs because it was a torture to listen to my own voice.”

Alagna was plagued by anxieties about his singing voice from a young age. Born to Sicilian immigrants, a bricklayer and seamstress, he grew up in the outer suburbs of Paris. When he was 10, he saw a television broadcast of the 1951 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Enrico Caruso biopic The Great Caruso, starring Mario Lanza as the star tenor. The movie made a deep impression. He had heard stories about his great-grandfather, a shopkeeper in Manhattan’s Little Italy, who used to sing for the Mafia with Caruso.

“It was a big shock for me,” he says. “It was my story. I was very impressed. And after that I start to sing. It was amazing. Hours and hours of singing with Mario Lanza.”

Despite growing up in an opera-loving household — or indeed because of it — Alagna was too shy to perform in front of his family. His sister was shocked to catch him singing in full voice in his bedroom one day; he begged her to keep it a secret.

“For me, operatic singers were heroes,” he says. “Like mutants, you know, like the X-Men. It was impossible for me to pretend to be an X-Man. But when I was alone, this energy was like a volcano, like magma. When I was alone in my house I sang like a crazy guy.”

Alagna eventually made his singing debut, aged 14, at a private function at his uncle’s Parisian pizzeria. In just a couple of years, he was performing professionally in four or five Parisian cabarets every night. He developed his stamina, his entertaining prowess and his vocal cords sharing the stage with topless dancers, illusionists and comedians. During the day, he studied opera and took singing lessons with Rafael Ruiz, a Cuban musician. For about a year, he worked as an accountant.

It was a punishing roster — one of Alagna’s lasting mementos of that time has been a lifetime of insomnia — but totally formative.

“In this cabaret I sang 70 songs a night. Every day you had to learn new songs. Singing, singing … I never had time to please myself or go on holiday. My entire life was singing and learning.”

Alagna was 20 when he met Luciano Pavarotti for the first time, at a record signing in a Paris department store.

“It was a big emotion. For me he was a mixture of Bacchus and Poseidon … it was amazing.” Years later, Alagna entered an international vocal competition judged by the King of the High Cs himself. In the first qualifying round, while the other hopefuls sang two arias each, Alagna sang one bar of Rossini’s La Danza before being interrupted. “You’re in,” they told him. Alagna won the competition.

Alagna married, had a daughter, and turned down his first invitation from the Met to perform in Der Rosenkavalier. “I said, ‘No, no! I’m too young.’ ” Other offers came in, and soon Alagna was performing major tenor roles in the world’s best opera houses, including La Scala.

It was Alagna’s 1994 performance as Romeo in Romeo and Juliet in London’s Covent Garden, however, that saw him anointed as an international star. He earned an Olivier Award and a pithy new moniker: “Now there is a fourth tenor,” wrote one critic. It stuck.

The experience ought to have been an unmitigated triumph, except a month before the show opened, Alagna’s wife had died of a brain tumour. “I was 29 when I lost my wife,” says Alagna. “She was 29 too. And I had my baby. It was so unfair for a beautiful girl like her.”

As emotionally charged as Romeo and Juliet was for Alagna, Orpheus’s grieving aria from Orpheus and Eurydice hits even closer to home to this day: Che faro senza Euridice? (What shall I do without my Eurydice?)”

“I was like this,” he says. “We were happy, it was the beginning of my career, with a lot of success. To have this kind of tragedy …” Alagna pauses. “It was terrible for me.”

Through the years, Alagna has continued to find comfort and catharsis in opera. It’s a kind of therapy, he says. Asked about the importance of emotional truth in a performance, Alagna says: “I tell you the truth. For me, I’m not trying to ‘play’. It’s all in the music. Sometimes it’s impossible not to cry because of the situation, because of the words … You are telling such beautiful words. Maybe I’m too sensitive. My entire life I’m like this.”

With that, you might begin to understand how Alagna’s emotions got the better of him on stage that night at La Scala 10 years ago, how those reverberating boos felt like death blows.

For starters, by Alagna’s own assessment, there was nothing particularly wrong with his performance; as he points out, it was the apparently jeer-worthy aria that ended up being used on the DVD. “Maybe it wasn’t my biggest night. But it wasn’t bad! Believe me. It wasn’t fair. It was political. No one understood very well what’s happened there.”

Fundamentally, though, Alagna admits he’s a lover, not a fighter. “I am not a warrior,” he says. “This profession — I want to give love to people. It’s not a battle. For me, when I am on stage, I want to give happiness. This art is divine, miraculous. To be on stage, for me it’s like a church for a priest. It’s a temple.”

The production of Manon Lescaut is something of a redemption — until the Aida incident, Manon Lescaut was to be Alagna’s next commitment at La Scala.

Alagna says he has been implored many times to return to Milan, not only by powers that be at La Scala but by some of those loggionisti who caused the fuss in the first place.

But he shrugs off the idea of going back. Even if he had the space in his schedule to consider it, Alagna is serenely satisfied with his career and life at the moment.

After a difficult separation in 2013 from his second wife — soprano Angela Gheorghiu, whom some have dubbed “Draculette” — he married Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzak. He became a father, for the second time, in 2014.

“Today I have a wonderful life and a wonderful wife, I have two daughters, I have a lot of work. I’m a lucky man.”

And, finally, he has made peace with his instrument.

“The voice is younger now,” he says. “When I was younger, I tried to make the voice darker, bigger. Today I have more serenity. Today I accept my voice, the colour of my voice. The most important thing is to give sentiment to people. And to have peace yourself.”

Roberto Alagna will perform in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane from July 21.