One hell of a tribute

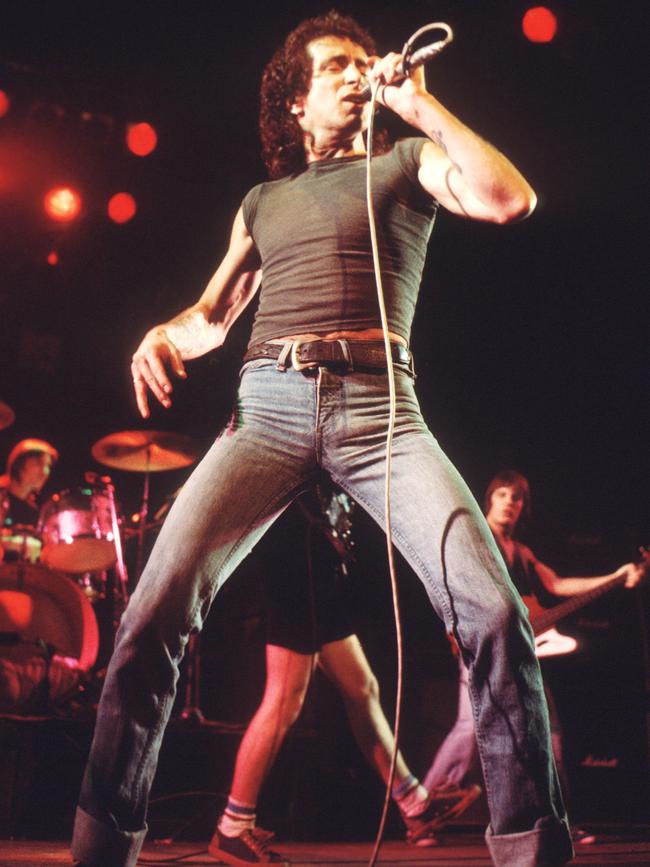

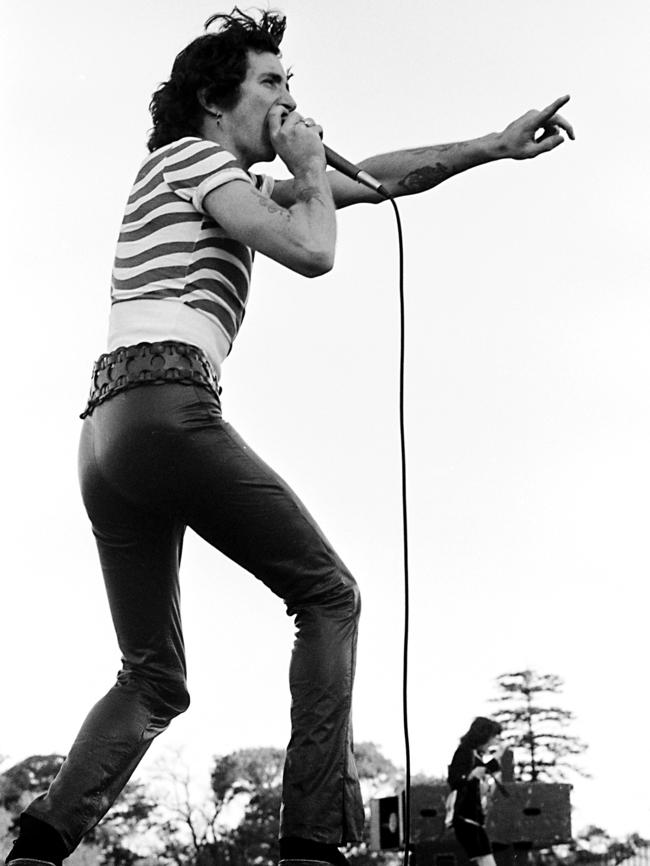

It’s 40 years since rock legend Bon Scott died, and Perth is honouring its lost black sheep in style.

The gravesite would be inconspicuous were it not for its freshly burnished brass plaque, casting off shards of light beneath a bleaching noonday sun. Bottle-tops, a purged bourbon bottle and crooked cigarette ends pockmark the earth beneath the modest cenotaph, its epitaph sober in its grief: “Loved son of Isa and Chick. Brother of Derek, Graeme and Valarie. Close to our hearts he will always stay, loved and remembered every day.”

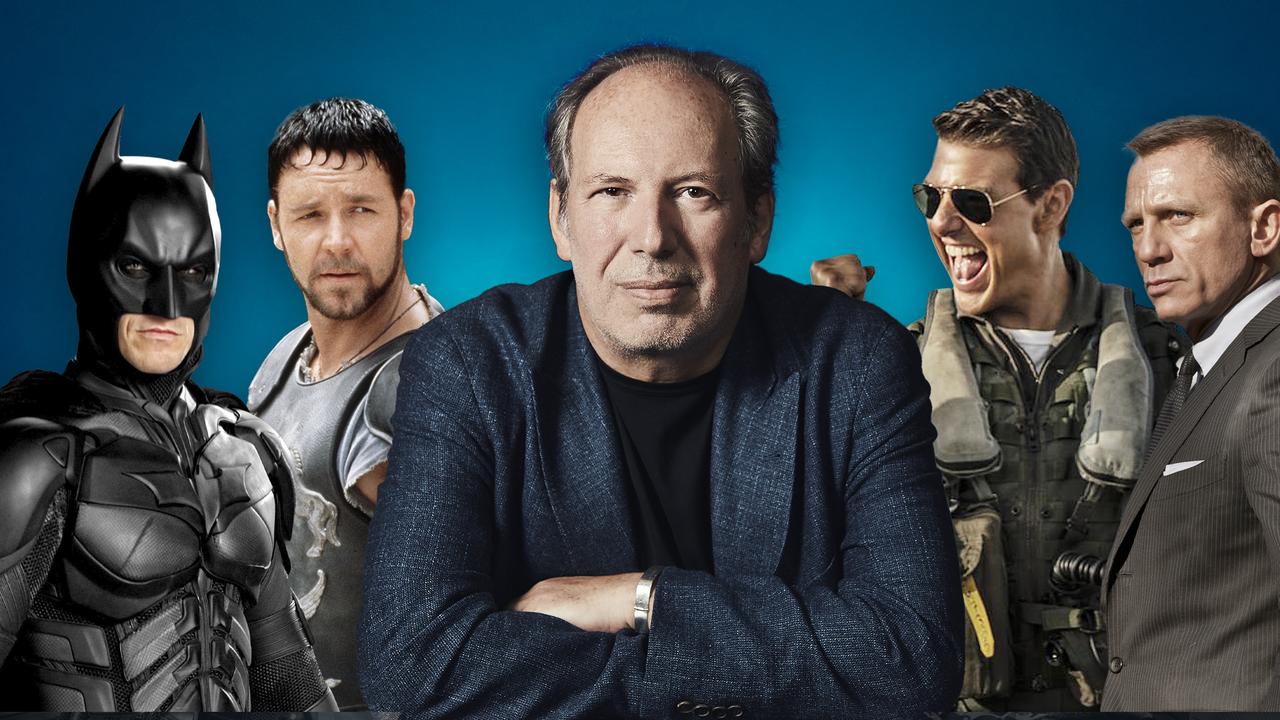

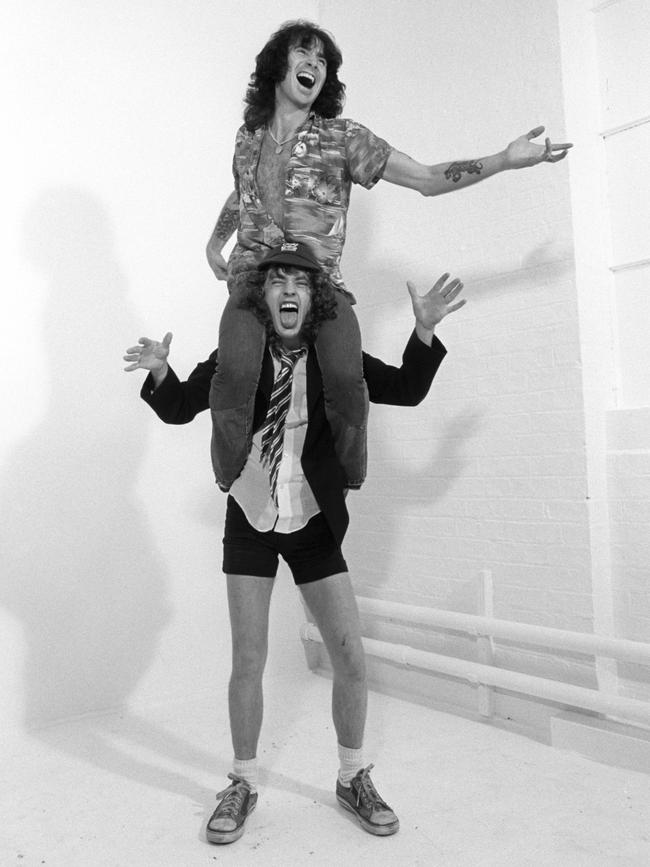

It has been 40 years since Ronald Scott was laid to rest at Fremantle Cemetery. Isa and Chick grieved for a lost son while Australia grieved for a lost icon. Ronald Belford “Bon” Scott had flamed out at his apogee on February 19, 1980: a casualty of rock’n’roll excess in London’s south, where he was workshopping new material with his bandmates in follow-up to the triumphant album that had transformed AC/DC from mid-tier pub-rock workhorses into one of the most formidable musical forces on the planet. That album was 1979’s Highway to Hell.

On March 1, Perth will commemorate the 40th anniversary of Scott’s untimely death under that very moniker in what’s been dubbed by organisers the world’s longest stage. One of the city’s busiest traffic arteries, Canning Highway will be locked down to traffic as a convoy of eight roving semi-trailers ferries a medley of local and international musicians along its 10-kilometre reach in tribute to WA’s favourite adopted rapscallion, channelling the Zeitgeist of the now iconic music video for It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock’n’Roll).

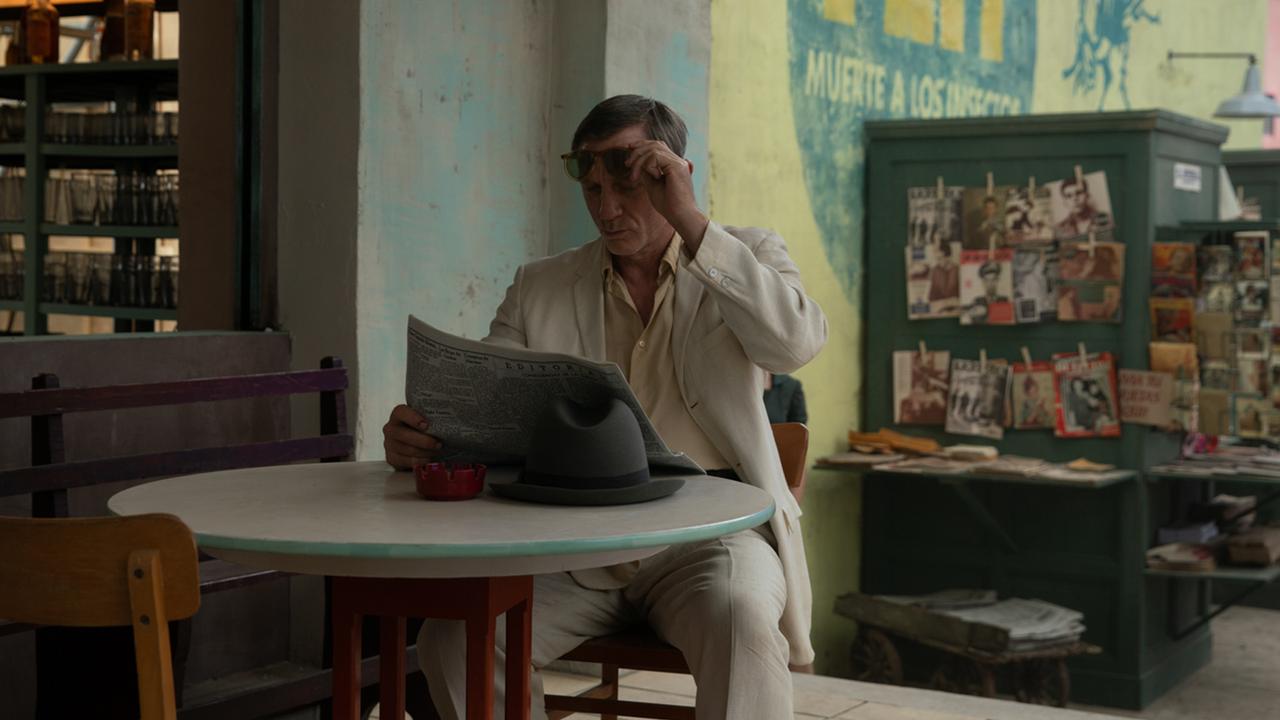

“Who doesn’t love a bit of AC/DC?” Perth Festival artistic director Iain Grandage chimes with a mischievous glint, reaching for his glass of beer at the historic Raffles Hotel on the banks of the Canning River, just south of Perth’s CBD. Now a polished gastro pub catering to the enduring business lunches of many a mining executive, it was here on the then notoriously sticky carpet that Scott honed his menacing stage presence and high-octane howl in early bands the Spektors and the Valentines, as well as AC/DC.

“It’s about celebrating every person who lives [in Perth], not just people who have pretentions to the highest art of European genesis,” Grandage continues, increasingly conscious as to not sound patronising. “It shouldn’t be analysed. It’s about the energy, it’s not about high art. It’s about great art and great music.”

Scott was long discerned by the West Australian establishment as a ruffian and peddler of social deviance, but WA’s political leaders and cultural elite have warmed to him in recent years – a slow thawing that in 2012 saw an altogether impish bronze statue of the otherwise larger-than-life rocker instated in Fremantle Fishing Boat Harbour (where he worked for a spell as a crayfisherman) and again in 2019 when the WA government bid nearly $14,000 to purchase a three-page letter penned by the late singer in 1978, bolstering the state’s growing Scott heritage collection.

“I’d love to check myself in to a sanitarium for a month but after this tour it’s straight to Europe & England for a month & then back here for the winter-end of the year so the next time you see me it might be in a geriatric ward (sic),” Scott wrote in that very letter to his friend, Valerie Lary, in the middle of one of the band’s most unremitting tours in support of the Powerage album.

-

A lot of it was bus and car touring, with no real break … It was a highway to hell. It really was. When you’re sleeping with the singer’s socks two inches from your nose, that’s pretty close to hell.

— Angus Young on AC/DC’s early days

-

It was during this tour Scott and his co-conspirators, Angus and Malcolm Young, penned the song that would become known as Highway to Hell. It has been enduring folklore in WA that Scott originally penned Highway to Hell about Canning Highway itself: an otherwise nondescript stretch of asphalt he knew as intimately as its foggy bars he’d haunted in his formative years, including The Raffles, The Leopold and The Tradewinds – all which are major junctures for the Highway to Hell celebrations.

It is more likely, however, Scott conceived the lyrics on a tour bus or catchpenny motel room while on the road in a year that saw AC/DC play more than 120 shows from Glasgow to Schaumberg, Illinois – and barely a day without the gruelling backwater travel in between. As guitarist Angus Young told Guitar World magazine in 1993: “A lot of it was bus and car touring, with no real break … It was a highway to hell. It really was. When you’re sleeping with the singer’s socks two inches from your nose, that’s pretty close to hell.”

Nonetheless, like It’s a Long Way to the Top before it, the song is emblematic of Scott’s improbable road to success: from the raw-knuckled backstreets of North Fremantle to the global stage. Grandage himself used to ply the very same highway in his own formative days between his home of Fremantle and the Perth Concert Hall in his Ford Escort panel van, replete with bubble windows and mag tyres. “There are a few anachronisms inside me,” the professional cellist and composer hollers, sheepishly admitting to playing fretless bass in a few “shite” rock bands in his early years.

“But in the end there was always enough suspicion that I, unlike Bon Scott, didn’t have ‘the thing’ that actually makes you a good onstage rock musician, that quality of charisma – that quality of transgression, energy and summoning from the other side. The otherness, which I’ve never had as I was always a tad too polite.” Grandage would later wreck his beloved van, crashing into the back of a Volvo while simultaneously driving and studying the score of the Mozart flute and harp concerto.

Scott was born in Forfar, Scotland in 1946 and reared in the family home in nearby Kirriemuir. A statue of the evergreen Peter Pan stands in the village square in honour of one its most famous sons, the author J.M Barrie, who is interred in the nearby cemetery. A short stroll away stands a monument to the town’s other favourite son: Scott, totemic bagpipes in arm and a fist raised towards the sky. It’s a debate that continues to smoulder to this day: is Scott – and with him AC/DC, and the Scottish-born Young brothers – Australian or Scottish?

The answer of course is both. Like so many post-war British working-class families, the Scotts left for Australia with six-year-old Bon in 1952 to seek a new life – first in Melbourne and ultimately to Fremantle in 1954. They took up in a red-brick Federation house, perched high between the Swan River and Indian Ocean on Harvest Road in North Fremantle: a mixed immigrant area of Brits, Italians and Greeks, bound only by their working-class predicament.

“We were all different, but we were all in the same boat,” Scott’s childhood friend, Robbie Williams, says over coffee, looking across to the former campus of North Fremantle Primary School, which they attended. Today the historic building is home to an elite childcare facility, emblematic of North Fremantle’s metamorphosis into one of WA’s more desirable addresses: now home to the likes of British writer and comedian Ben Elton and international basketball identity Luc Longley. “It was a f..king rough place, and you needed to be tough to survive it.”

Demarcated from Fremantle proper by the Swan River and connected by a rickety old traffic bridge, Scott’s North Fremantle was a place of larrikinism, poverty and ruthless gangs, and the punch-ons staged beneath the old mulberry tree between Scott’s house and the river have become a thing of legend.

Scott was well known to local police from a young age – yet another delinquent terrorising the streets and larking about in the river waters at Harvey Beach. Like many locals, as a teenager Scott would drift between itinerant work at local factories such as West Wools, the Weeties factory or the aniseed farm on the banks of the river – then spend his evenings flirting or fighting at Bells burger joint, or in one of Fremantle’s countless rough-hewn pubs, with their incendiary olio of wharfies, fisherman and US navy marines.

But music was always there: in his blood and in his purview. Like his father, he joined the Coastal Scots Pipe Band based in the Fremantle Railway Workshops, where he played percussion. By 1964 Scott had dropped out of high school and formed his first pop band, the Spektors, as drummer and occasional vocalist, playing workers clubs and stomps at Port Beach hosted by local pop celebrity Johnny Young.

It was at one such Port Beach dance that local police would finally arrest Scott, this time for carnal knowledge, leading to a few days processing in Fremantle Prison – one of the country’s most notorious convict-era penitentiaries and then home to mass murderer Eric Edgar Cook, aka the Night Caller and Nedlands Monster, also interred at Fremantle Cemetery – before being transferred to Riverbank Juvenile Prison where he saw out his sentence.

On his release Scott would return to the Spektors with fresh resolve: he was either going to break out of Fremantle in a band, in the back of a paddy wagon or in a hearse.

Robbie Williams cuts the engine in front of the former Scott family home, largely unchanged from the one he remembers, save for a few cosmetic nips and tucks. It was in this house Williams first saw Scott play drums – a shimmering gold kit that’s seared itself into his memory. “I asked Bon ‘why drums?’ and he said, ‘well, if you’re shit on the drums then they’ll make you the singer and if you’re shit at that then as a last resort you can always become the band manager’.”

Williams took heed of the elder Scott’s street-smarts and went into management, steering the career of local 70s sensation Supernaut before going on to manage Rose Tattoo, and later founding the country’s premiere touring agency, Frontier, with Michael Gudinski and Michael Chugg. He would later head up AC/DC’s record label, Alberts, in the UK and Europe.

“Bon was like the rest of us, just another working-class kid with no real future,” Williams offers, pulling up in front of the historic Weeties factory – now a designer warehouse apartment complex – where the local kids used to scramble at the day’s end hoping to be shown pity with any throwaway foodstuffs. “For blokes like him and I, as inconceivable as it was, music was the only way out.”

After two years in the Spektors Scott joined the Valentines: a new all-star group featuring some of the city’s finest musicians, featuring on co-vocals Vince Lovegrove, who would go on to manage the Divinyls and become one of the country’s most prolific music journalists and authors. The band’s saccharine brand of bubblegum pop continues to bewilder many devout AC/DC fans to this day. But ever the blind-siding chameleon, Scott knew music was his ticket out and in 1970, while touring on the east coast with the Valentines, he would fall in with Fraternity: a jam-rock group channelling the second-hand Zeitgeist of bands such as Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead.

While Scott was originally drafted to play recorder, he would graduate to vocals and the band would soon relocate to Adelaide, where it enjoyed a hit single with Seasons of Change, back when Australia’s music markets and charts were fiercely localised. It was in Adelaide in 1974 that fate would cause a sonic head-on collision between Scott and a penniless Sydney band stranded in Adelaide named AC/DC, whose lead singer, Dave Evans, had just been ousted. Scott retired his recorder and stepped up to the microphone. He’d be replaced in Fraternity by another Scottish hollering upstart named Jimmy Barnes.

Highway to Hell brings together a motley assortment of artists in celebration of Scott – from Perth singer-songwriter Abbe May to Japanese all-female group Shonen Knife.

“Bon Scott is rock,” Shonen Knife’s Naoko Yamano offers from her home base in Osaka. “That’s all I’m trying to do as a frontwoman: to channel what Bon did and to be rock.”

Tens of thousands of locals are predicted to line Canning Highway for Highway to Hell, with government entities, local businesses and community groups embracing Scott’s own brand of recalcitrant candour. Transperth – the city’s public transport operator – has branded a special festival bus the 666 route, while a local Baptist Church branch has created a “chill-out hub” in a local church cheekily named the Highway to Heaven.

While Grandage seems all too aware of the cruel paradox in consecrating a felon who sung both of Perth’s stifling ennui and catching venereal disease, before ultimately dying at the end of a bottle, he’s also acutely aware of Scott’s unrivalled audience reach and Australia’s curious penchant for venerating outlaws. “Just when I began to think it was too ambitious you would suddenly get the Premier [Mark McGowan] telling you he’s an AC/DC fan and getting behind it, and that would push you on.”

Indeed, Arts Minister David Templeman quite literally broke into song when announcing Highway to Hell in late 2019, hollering an a cappella rendition of 1980 hit You Shook Me All Night Long: a mystifying choice, lifted from the band’s first post-Scott album, Back in Black, featuring new singer Brian Johnson: the only album to surpass sales of Highway to Hell.

“I’m not going to gloss over it, it was tough,” Highway to Hell producer Pete Stone says of the logistics. “But it’s amazing when you start to knock on doors to people of power how many are outed as AC/DC fans. Everyone was on board from the start, so it wasn’t so much ‘can we do it?’ as ‘how do we do it?’. Unlike most artists, Bon Scott seems to transcend age and genre … he belongs to everyone.”

Highway to Hell is free; Canning Highway, WA, as part of the Perth Festival on March 1.

RELATED STORIES: What’s on the culture calendar this March | Tao of Glass by Philip Glass and Phelim McDermott