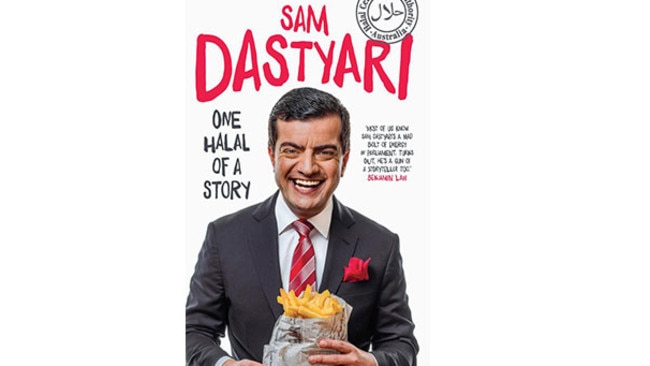

One Halal of a Story by Sam Dastyari: Labor stars rise and fall

Many Australian politicians have written candid books about their time in Canberra. Few have done it quite like Sam Dastyari.

Sam Dastyari wants you to like him. Made general secretary of the Sydney branch of the ALP when he was barely out of nappies, he was elected to the Senate in 2013, the first person of Iranian origin to sit in an Australian parliament. Ever since, it’s been hard to escape the 34-year-old senator. He’s a grand vizier of social media, appears on every TV show that’ll have him ... and now there’s the furore over his memoir, One Halal of a Story.

Dastyari is embarking on a bit of a rebrand. He was forced to resign from Labor’s frontbench 12 months ago when it was revealed a Chinese donor had paid one of his travel bills. Around the same time, he backed the Chinese regime’s line on the South China Sea, which is opposite to Labor’s. He has denied any connection between payment and opinion, but the perception hurt him.

His memoir has launched a thousand media thinkpieces. Should he be forgiven for taking Chinese money and spinning the web of Chinese foreign policy? Was ABC TV’s Australian Story special on Dastyari and his book an example of elitist lefties sticking together no matter what? Is he just a failure, as one writer in The Saturday Paper put it, who represents the smallness of our political world?

Well, I’m tasked with one only question here: is Sam Dastyari’s book any good? It is. It’s one of the warmest political memoirs I have read. A lot of Aussie pollies have written candid enough books about their time in Canberra. Others have scripted interesting policy manifestos. But few politicians cum writers have the warmheartedness and humour that Dastyari boasts in bucketloads.

The book starts in post-revolutionary Iran. Dastyari’s mother is making the biggest decision of her life. And the ayatollah is watching:

My mother, whose name is Ella, likes to tell me about the exact moment she decided she would have me. It was 26 September 1981, and it was the day she was not executed ... For my mother, it was possession of a political pamphlet that brought trouble her way. She read propaganda in the form of a newspaper. This might seem innocent enough when others are killing each other with bullets and bombs but the regime understood that ideas mattered.

The extraordinary stories of Dastyari’s parents, student revolutionaries whose rebellion was stolen from them, feed into his touching portraits of the earlier generation. The fierce women of the family with feminist ideals before feminism existed. His post office-working grandfather saved young boys from the Iran-Iraq war by burning the letters they sent to the Revolutionary Guard volunteering to die.

The family came to Australia in 1988. We read the adventures of young Sam. There’s his mother reading tea leaves for the white women on the street, the small business empire the extended Dastyaris amass where Sam slaves away (and is often sacked). Then there are great, self-deprecating stories of growing up foreign in Sydney, tinged then and now with a sadness and a continuing quest for acceptance.

As attractive and feel-good as the Dastyari Show is, it will disappoint readers who want the politics. There is no hot gossip, no takedowns of Dastyari’s enemies (The Latham Diaries this is not). What shines through instead is his ability to connect with ordinary people.

His proposed inquisition of the banks is seen through the eyes of a terrified whistleblower. His passion for indigenous rights is told through the stories of young volunteers in remote communities (Dastyari has no time for lefties who are all talk and no action). It’s all part of his ability, eagerness even, to put himself in other people’s shoes.

Then there are the regrets. He talks about his time leading the NSW Labor machine into the abyss at the time of the 2011 state election that saw Kristina Keneally lose in a landslide. There’s the Rudd-Gillard wars and his role as one of few faceless men loyal to Kevin 07 throughout the entire period.

And then there’s the scandal. Dastyari admits he was “dumb” to take a Chinese donor’s money to pay for his travel bill.

“I was naive. I made a mistake in letting someone sort a bill. This was a bill, as I said, I had declared, but I should have had the prudence to foresee that opponents might run with the payment of the expense in order to question my motives.”

It’s not exactly begging for forgiveness, is it? And it’s a bit worrying that the more serious sin of parroting the lines of the Chinese Communist Party seems pretty lost on him. “The allegation was that I contradicted ALP policy on the South China Sea. I’m not sure that I contradicted it. But that doesn’t matter.”

Dastyari is frank, if not totally contrite, about the scandal that almost destroyed his political career. That’s rare enough in Australian politics and it’s not to be sneezed at.

Today he’s working his way back to the frontbench. He’s still the Senate’s best negotiator. He still has a media profile that eclipses two-thirds of the Labor frontbench. Why is he not dead? It’s because he’s genuinely interesting and he speaks like a living, breathing human being

Yes, Sam Dastyari wants the readers of One Halal of a Story to like him and preferably forgive him. Well, you don’t have to. But read his book anyway. It’s a ripper.

Richard Ferguson is a journalist with The Australian.

One Halal of a Story, By Sam Dastyari, MUP, 277pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout