Not the man they think he is at home

He’s sold 150 million albums and been famous for five decades. But do we really know Elton John?

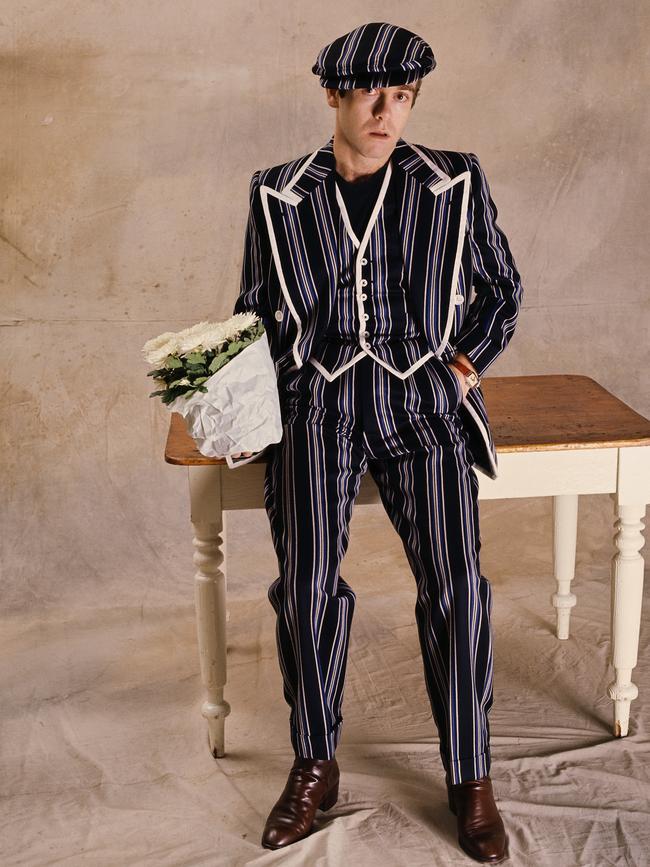

There is an incident from early on in Elton John’s career that reminds us how peculiar it has been. The year was 1970. John’s first album, Empty Sky, had been released in Britain but had gone nowhere. His label, supportive of him in fits and starts, eventually laid out for a decent producer and some lush orchestrations for his second album, which was self-titled and came out that spring. Today we know Elton John as a lasting and flamboyant star; put that aside for now and remember that back then no one was thinking in those terms about the plainly talented but pudgy and somewhat morose 22-year-old they were working with at the time.

The first single from Elton John, Border Song, was a flop. The label’s next move, for some reason, was to dig out a non-album track and release it as the second single, hoping to garner more attention that way. That release, Rock and Roll Madonna, went nowhere, either. The label went back to the album, poked around some more and made a third try, with Take Me to the Pilot.

It wasn’t a hit.

By this time other things were going on in John’s career. The shy boy behind the scenes found a raucous personality on stage; he and a small band had flown to the US and had wowed the industry with a cacophonous six-night stand at the famous Troubadour nightclub in Los Angeles. And by this time John had finished a third album, Tumbleweed Connection, which was released that October.

That’s when something interesting happened. Late in the year some radio DJs checked out the B-side of the Pilot single, which was a throwaway track from the Elton John album. They began to play it. This was not typical at the time. The B-side was a forlorn-sounding piano-based track. The first words of the song went: “It’s a little bit funny / This feeling inside …”

A few months later, in early 1971, nearly a year after the release of the album, the B-side was a top 10 hit in the US and Britain. The track, Your Song, is a standard today, nearly 50 years on; it is one of the most played radio singles of all time and has been covered by scores of artists, perhaps hundreds. But isn’t it weird that no one — label execs, marketers or journos — thought it was a single back then, or even notable? For some reason, even experienced music industry people at the time couldn’t “hear” the song.

In some fundamental way, Your Song was unusual. The melody is sturdy, of course, and the chorus is plainly as lovely as can be but there was something about its formal presentation — coursing strings, a prominent, tasteful bass, a subtle but insistent set of piano fills — that wasn’t registering. Maybe it just wasn’t cool enough. As for the lyrics, their premise — “I’m writing a song about writing a song for you” — has some remote Cole Porter overtones, I guess, but there’s nothing droll or arch about it; indeed, if anything, it suffers from over-sincerity. It was the end of the psychedelic era, remember, and the more sombre singer-songwriters had their roots in folk and blues. Your Song is arguably a traditional pop ballad but it’s conceived and performed with a somewhat shambling but definite rock ’n’ roll authenticity. The writing is elegant and prosaic at the same time; are the lyrics conversational and halting or exquisitely crafted to sound that way? I think, in 1970, the people first confronted by the song couldn’t process what is, for us, today, its patent brilliance because they hadn’t heard a song like it before. It’s familiar to us today because we live in a world that Elton John has made his own.

Indeed, to many, John is a bit too obvious now: the teddy-bear pop-rock star, the burbling sidekick of royalty, the ageing, bewigged gay icon. But that cosy mien has always hidden something uncompromising and a bit strange underneath. He is a dubious figure set against the high intellectualism of Joni Mitchell, say, or the assuredly more dangerous work of Lou Reed, or that of David Bowie, and on and on. But in his own way, originally, and then definitely as his acclaim grew, he found his own distinctive passage through the apocalypse of the post-Beatles pop landscape — and offered us ever more ambitious pop constructions, culminating in some sort of weird masterpiece, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, and then an odd autobiographical song cycle, Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy, in which he looked back to examine his life and the years of insecurity preceding his stardom.

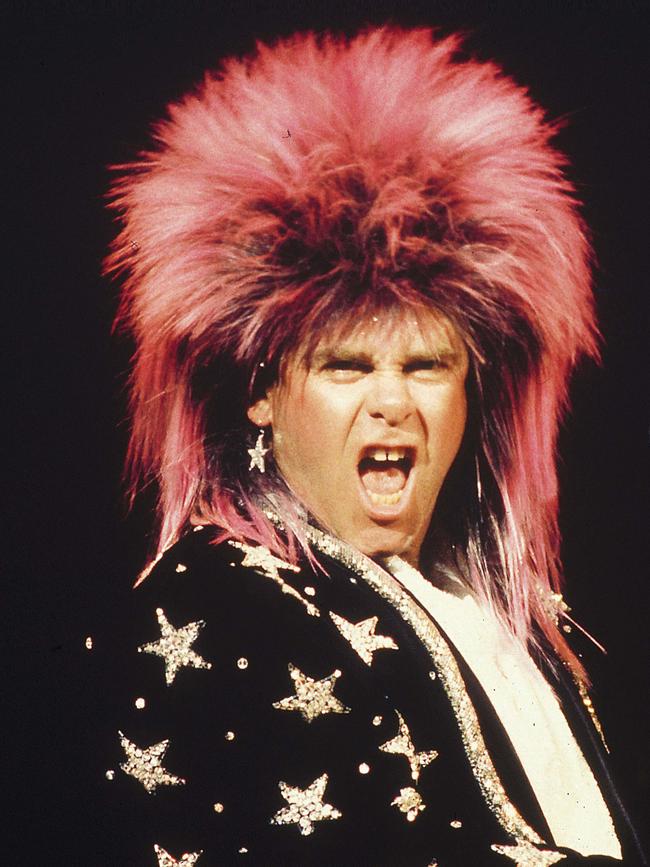

Those were his artistic achievements. His commercial ones were even bigger. Bowie looms large in rock history now but in the US, in the early 70s, he was nothing close to a star. John famously took sartorial flamboyance to almost transvestite levels but was treated as a curiosity and never registered as transgressive. He had seven No 1 albums in a row in the US. These albums, in a 3½-year period, spent a total of 39 weeks at No 1, a bit less than a quarter of that overall span. He had a similar success in Australia and Britain. By Billboard’s rankings, he is by far the biggest album act of the 1970s. He is also Billboard’s biggest singles act of the decade and the magazine’s third biggest singles artist of all time, with nine No 1 singles and 27 top 10 hits, which is a lot. In all, he has sold more than 150 million albums and 100 million singles.

««««

Fifty years into his career, John has embarked on what is supposed to be his absolutely final Farewell-Goodbye-I’m-Retiring-I-Really-Mean-It Tour. The first time he announced his final show was in 1976. “Who wants to be a 45-year-old entertainer in Las Vegas like Elvis?” he said at the time. (He played his 449th and 450th Las Vegas shows, supposedly his final ones, this month, at the age of 71.) The new tour began in the US, in Allentown and Philadelphia, and will touch down in Australia in November.

But for the record, it should be said that if there is one thing John is not, it’s obvious. He doesn’t write his own lyrics; he has spoken to us, if he has at all, through the words of other lyricists, most prominently Bernie Taupin, with whom he formed a songwriting partnership in 1967 that lasted through the entirety of his classic years. Through the decades, the themes and subjects of Taupin’s words have benignly reflected on to the singer’s persona, even though we have no reason to think they accurately represent it. And John’s songwriting process make their significance even more obscure. The pair didn’t (and still don’t) work together; instead, John walks off with Taupin’s scrawls and, with uncanny speed and focus, makes the songs he wants out of them. In effect he has always made Taupin’s words mean what he wants them to mean, giving himself the room to identify with or distance himself from them at will. In other words, if you think you know Elton John through his songs — you don’t.

He was named Reginald at birth by his parents, Sheila and Stanley Dwight, and was reared in the far-northwestern London suburb of Pinner. His father left the family after some confusing situation of sexual imbroglios; John remained very close to his mother and was reared by her and a stepfather. He was something of a musical prodigy, entering the Royal Academy of Music on a scholarship at 11. By his own account he soon realised that (a) he might be able to become famous and that (b) he would very much like for that to happen. He left school at 17 and struggled over the next five or six years, bouncing around in the London music scene, finally ending up in a band called Bluesology.

He was just another one of the dozens if not hundreds of anonymous London musicians trying to make sense of their talents and of a new world after the success of the Beatles and of course the Stones — hence the name Bluesology — with varying degrees of ludicrousness.

John was next in the band of a respected British blues rocker called Long John Baldry, who for some unearthly reason ended up riding high, temporarily, with a bizarre Anthony Newley-style hit single called Let the Heartaches Begin. Forgotten now, Baldry was a key figure of the scene in his own way. He was out and open about being gay when homosexual acts were still criminalised in Britain. After some dutiful relationships with women, John, perhaps inspired by Baldry, came out to his friends and family early on — a brave step at the time.

Still, he was by his own account lost in many different ways. He and all who knew him talk about how plainly unsuited he was to his desired role. Among the cool mod boys he was indeed — the word is used incessantly — pudgy. He cleaned up for photos but video from the period shows him a slightly goofy and only glancingly charismatic figure in person. His hair, as always, was a disaster and he was in no way close to the model of rock-star handsomeness. His personality — the musical equivalent of bookish, maternally dependent, insular — didn’t help. But one day he answered an ad for a small record company, Liberty, and through that auspicious action was put in touch with someone who wanted to write lyrics. Bernie Taupin, as he has written in many songs, was a country mouse in the classic mould, a shy boy from the rural county of Lincolnshire. He dreamt not of stardom but of America, writing down words in his prosaic, engaging style about what he imagined America, and particularly the American west, to be from his bedroom in his parents’ house. He was 17.

The pair was introduced, hit it off and soon were living together in John’s mother’s house in Pinner. “We were swimming in deep water and both needing someone to hang on to,” Taupin said later. (Taupin wasn’t gay, however.) They wound up working in-house writing songs for Dick James Music. John and Taupin had some success, by the degraded standards of the day, writing crummy pop songs for hire. One was actually sung by Lulu in the hullabalooed competitions for the Eurovision song contest. But in time younger folks at the company started letting the pair work on material for John to perform. That led to Empty Sky, and then to Elton John, and then — once Your Song hit — to John becoming something no one expected: a familiar and welcome part of the lives of an enormous number of people.

Strings were always a part of Beatles-era pop and a staple in 60s pop-schlock, too. The producer of Elton John, Gus Dudgeon, and its string orchestrator, Paul Buckmaster, stayed with John over his next half-dozen or so releases, expanding the sound of the music with every release. A year later they helped achieve John’s ambitious vision for the title song of Madman Across the Water. It’s a dumb title, but the song has a great soundscape, rattled by Buckmaster’s stinging orchestra lines. The strings dominate Madman’s Tiny Dancer and Levon, too; it’s possible the strings — in both cases dark and dramatic, nothing like bright pop accoutrements — might have limited the two songs’ commercial appeal at the time but they are both radio standards today.

John moved towards shorter and poppier songs, with increasing facility: Honky Cat, with its inside-out version of a New Orleans rag; Rocket Man, a mournful track about space travel and modern anomie with a defiantly acoustic backing; Daniel, a soft-rock classic with a mysterious storyline; and Crocodile Rock, a sock-hop re-creation. This all culminated in Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, at the time the most successful two-record set of pop songs since the White Album. Some of it seems erratic today — Taupin was getting a little garish, dabbling in strained exotica with too many songs featuring hookers and lesbians — but the set had a bravura first side, forever cementing John’s reputation as a creator of pop grandeur: Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding, more than 11 minutes long; the killer Bennie and the Jets; and Candle in the Wind, with another deceptively conversational lyric from Taupin. Here and there throughout the album there are enough enjoyable titbits (The Ballad of Danny Bailey, Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting, Roy Rogers, the pretty closer Harmony) to make the case that it’s not a disc too long.

As for Captain Fantastic, it’s a jointly done autobiographical song cycle about an unlikely songwriting partnership, sweet and sour by turns, but with an overall cast of sunniness. This does not sound like the makings of a great rock album but to get there you have to dismiss the audacious conceit of the title song — the John-Taupin collaboration’s most successful bit of mythologising and one of John’s best straightforward rock songs — and the most naked bit of self-revelation in John’s classic years, the song Someone Saved My Life Tonight. The song is based in reality — John and Taupin had at one time shared an apartment with a woman to whom John had dutifully become engaged. He broke it off at the last minute after a talking-to from Baldry. The song is nasty in parts towards a woman who in real life probably doesn’t deserve it. But the track, then as now, is an emotional maelstrom; and through the years John, even at his most vulnerable, has found great power in it. In this song and in various other ways, John was leading a double life; he was a shy person donning outlandish get-ups on stage; he was a gay man singing love songs to women; he was a casual star who, behind the scenes, was creating with a determined velocity.

He had been cranking out the equivalent of two albums a year and touring besides. Later in the decade, pulled into therapy by a lover, he admitted he was addicted to just about everything — to pills, other drugs, alcohol, sex and food. At the end of his commercial period, he looked awful, prematurely middle-aged; his music lost much of its joy and mischievous nature. “He went very Judy Garland on us,” a friend said, somewhat cruelly. He took a year off to get his life straightened out but he ended up semi-sleepwalking through the 80s before he cleaned up entirely in the early 90s.

I’d had a lingering idea that Blue Moves, another ambitious two-record set coming after Rock of the Westies, his last hit album of the 70s, might be a neglected John masterpiece, anchored by the ultra-torch song, Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word, but it’s not. Blue Moves is a barely listenable aggregation of substandard songs, flintily produced. John never recorded an album after that you might play for someone to convince them of his talent, but even in his decline he still doggedly created the occasional top 10 hit, and once in a while broke through with a good song (I Guess That’s Why They Call It the Blues, I’m Still Standing, Sacrifice), with a little help from MTV. And in 1997, of course, bereft at the death of his friend Princess Diana, he retooled Candle in the Wind for her funeral, which just about everyone watched in September of that year. The song is by most accounts the largest selling single of the modern era around the world.

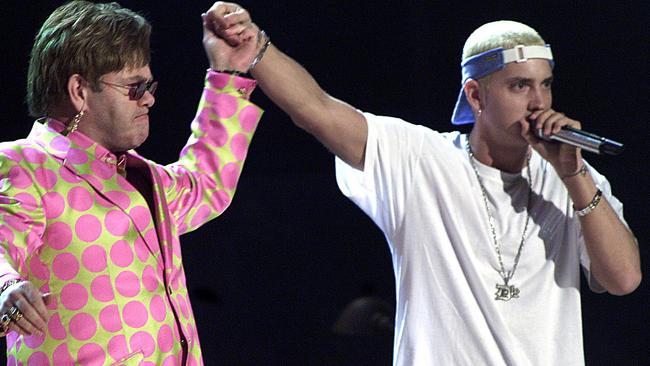

Call that appearance purely sentimental but he made other, tougher public positions, too. On the eve of the 2001 Grammys, some controversy lingered about the inclusion of rapper Eminem, then in his most manic and offensive phase, in the show; The Marshall Mathers LP was nominated for album of the year. Eminem was under fire for recurring misogynistic and homophobic slurs. Yet, at the show, after Eminem rapped through the first verse of Stan, the chorus (sung by Dido on the single) was delivered, after a sensational reveal, by one Reginald Dwight, pudgy but plainly determined. Protest is fine, John was saying. But you can also respond to knuckleheads with love.

««««

There are plenty of songwriting partnerships in rock, of course, but the John-Taupin set-up is disconcerting, involving issues of identity, authenticity and persona. Taupin heavily romanticised America and American culture, particularly the west and, less convincingly, the south; John may or may not have cared about it but he dutifully mouths the words Taupin gave him in the song cycle Tumbleweed Connection, the songs Roy Rogers and Indian Sunset, and many more. (John never ran from or hid his Englishness, however.)

In Blues for Baby and Me, John begs his (female) lover to come with him and head west on a bus. This matters, right? Hard to imagine John himself would ever want to induce a woman on to a bus in the first place, much less head west on it. And then, even as John collected Rolls-Royces and embarked on a jetsetting lifestyle that would span nearly five decades, again and again he delivered Taupin’s laments of the country boy scalded by the hot flame of the city (Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, and on and on). Yet he sang the songs convincingly and we accordingly projected on to him the romantic schema of Taupin’s conception. Insular, shy Reg found that this suited him just fine; his great talent was to adopt the persona and rise up and make those flights of fancy real for his listeners. This is an old pop model — the rock one of authenticity calls for the singer to write their own songs, right? John up-ended that and used Taupin’s fanciful concoctions to maintain an image of harmlessness.

John has always had the musical skills to make it work. He is an amazing pianist; his body of work is a seemingly unending flow of fairly complex, full-bodied playing, with counter-melodies cascading through almost every song. John was 71 when I saw his last two shows in Las Vegas last year, and I was close enough to marvel at the way he pounded the top registers of the keyboard with just his right hand. Later, I tried moving my arms in a similar hammer-like motion and got quite tired of it after about 45 seconds. John did it for more than 90 minutes. (I have the sense that his new farewell tour shows — staged on a much larger scale in much larger arenas — are less physically demanding on him.) Among other things, he brought back to pop the manic piano styles of Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard after a decade of neglect, but he also took the piano into relentlessly expansive (and always melodic) places. The vast majority of the time, he uses these talents for meaningful and tasteful effects, whether pounding out the 50s riffs on Crocodile Rock, limning the barren landscapes of Madman Across the Water, building up the subtly intensifying dynamics of Tiny Dancer or just achieving that alluring cinematic expanse with that single portentous piano chord in the first 12 seconds of Bennie and the Jets.

John’s disclosure of his sexuality came towards the end of his classic period, in an appropriately nuanced but patently honest rumination on the reality of his life. The venue was a cover interview in Rolling Stone, where he described himself as bisexual and detailed both when he’d lost his virginity and when he had first slept with a man (the latter “probably a good year or two” after the former). This was near the end of his chart dominance. The unmistakeable commercial drop-off he experienced soon after can’t really be attributed to this — it’s not like he was still cranking out great pop songs — but the mixed reaction probably was another one of the demons that chased him for the rest of that decade and through the 80s. He’d bought a British soccer team — Watford FC — by this time. After the interview came out, the team endured much derision in the sports world; according to Philip Norman’s biography, Elton John, fans yelled homophobic slurs at the team for years afterwards. This might have been why John, like virtually all of the pop stars of the 70s and 80s, was shamefully silent about the ravages of AIDS. Unlike most, however, he has been forthright about this, as he has with so many other things. “I didn’t get my hands dirty,” he has since acknowledged. “I was too much of a drug addict, or too self-obsessed, and I’ve been very ashamed of that.” Is there another rock star, living or dead, who could have uttered those words?

««««

The Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour — a greatest hits affair, with all-new staging — is a lot of fun. The show is a gracious, impressive affair of hit after hit after hit. In Allentown he took time out to recognise not only Aretha Franklin, who did an early recording of John’s Border Song, but also Mac Miller, a young rapper who had died the day before. In Philadelphia he told the crowd he’d played his first show there exactly 48 years earlier, on September 11, 1970, and that drummer Nigel Olsson and Taupin, both there on the tour that night, had been there in 1970, as well.

On an enormous video screen above the stage, he proudly showed off photos of himself as a young, besuited child, seated at a keyboard, like any mother’s pride and joy — and also photos with his husband, David Furnish, and their two young adopted sons. And there were many, many shots of John in all of his extreme costumes.

It’s a little bit funny how some of the songs, in which he so often occluded meanings, now actually seem to have genuine significance. The cruel words in the second verse of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road fade away now. The road he’s saying goodbye to now is a real one; the home he’s going back to is inhabited by a new family he belatedly seems to have formed, satisfactorily, on his own. Your Song, too, is something entirely different. John was estranged from his mother for much of the last decade of her life. They made up before her death. When she died, in 2017, he continued with his then-current tour but spoke feelingly of her support for him in his early years, and sang Your Song to her memory, finding in the tune a very different kind of love.

In Allentown, when he sang that song, he gave a detailed thank you to everyone who had shown support for him over the years, all the way back to the buyers of eight-track tapes and 45rpm singles. “Thank you, from the bottom of my heart, for everything you’ve given me,” the 71-year-old said.

In that moment, 50 years of sincerity and respect hovered between star and fans, and no one there, myself included, did not stand up to give him a simple but prolonged ovation, for many years of music but also for being, within a shitty industry, an unconventional star and a purveyor of wonderful songs, dependable to the last.

The Australian leg of Elton John’s Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour begins in Perth on November 30 and ends in Victoria in February next year. Rocketman, the film, is released on Thursday.

NEW YORK MEDIA

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout