No place like Glasto: The intriguing history of world’s most important music festival

Glastonbury’s improbably romantic history chimes with its ethics and impact. What is the allure of the often muddy music festival?

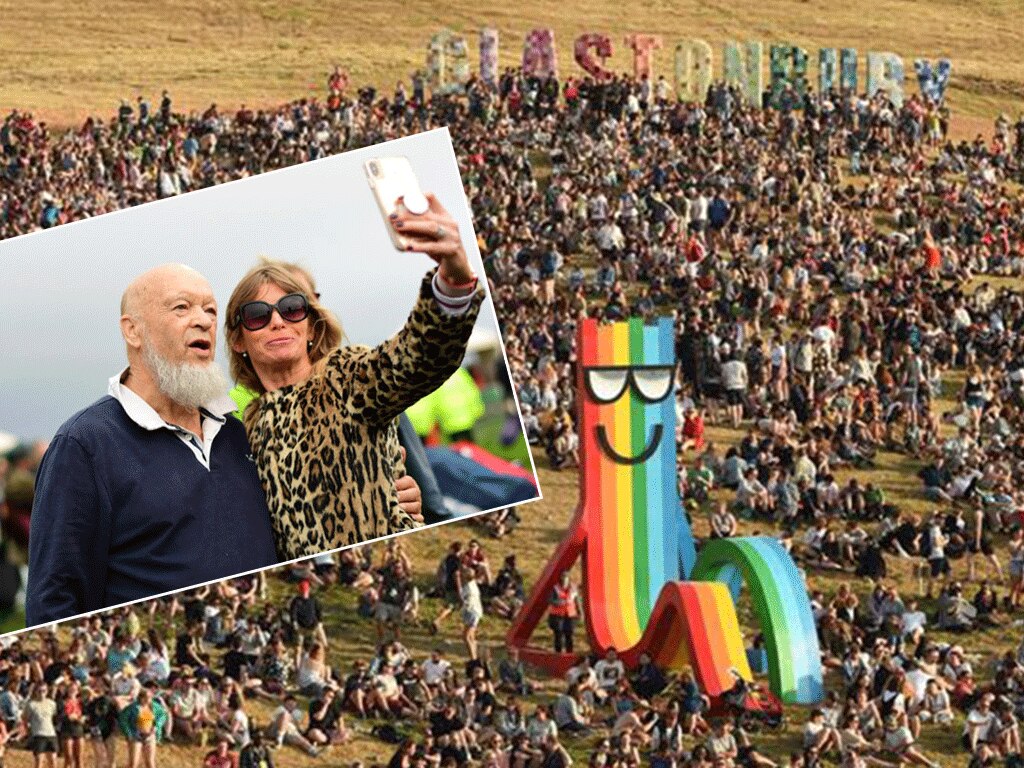

As the world’s biggest, most beautiful greenfield music and performing arts festival – and, as its passionately idealistic co-creator Michael Eavis, now 87, describes it, “a template for all the festivals that have come after it” – Glastonbury holds a unique place not only in the music industry, but the collective consciousness. With its celebrity guests – A-List actors and models, multi-millionaire footballers, British royals – splashed across the global media, its Arcadian backdrop, and cameos in major films – one of the funniest sequences in Bridget Jones’s Baby (2016) was set in a faux-Glasto, and Academy Award-nominated actor/director Bradley Cooper surprised festivalgoers by appearing onstage in 2017 as character Jackson Maine for a scene in A Star is Born – it is the shamanistic heart of England’s Season.

John Robb, bestselling author of The Art of Darkness: The History of Goth, describes Glastonbury as the soul of British pop culture. “Beginning as a remnant of the freak flag culture of the 1960s, it’s now a joyous, high-decibel, multi-genre recharging of the human spirit,” he writes.

This year’s line-up, headlined by the Arctic Monkeys, Guns N’ Roses, Sir Elton John, Cat Stevens, Maneskin, and Lana del Rey (who almost pulled out after her name wasn’t sufficiently prominent on the poster) saw 210,000 tickets at £340 ($646) sell out in less than an hour.

As Noel Gallagher, formerly of Oasis, said in an interview, “There are literally hundreds of festivals in the world, and I should know because I’ve played most if not all of them. The funny thing is, though, there’s really only one festival in the world – in the truest sense of the word, anyway. Glastonbury is more important than Christmas.”

A canvas-tented mini-state, Glasto (as it’s known in England) appears for five days each summer and then vanishes, a Brigadoon in greenest Somerset: 900 acres in the Vale of Avalon, a region with an eight-and-a-half-mile perimeter steeped, as Eavis wrote, “in symbolism, mythology and religious traditions dating back many hundreds of years. It’s where King Arthur may be buried, where Joseph of Arimathea is said to have walked, where ley lines converge”.

This improbably romantic history chimes with the festival’s ethics and impact. Dairy farmer Eavis and his daughter Emily, who now helps run the festival, donate more than £2m a year to their partner charities – Greenpeace, Oxfam, and Water Aid – among other humanitarian endeavours. In 1981, Eavis realised its philanthropic potential when £20,000 was made in profit: he donated it all to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (“I took it down on the train myself”).

Appropriately, the festival’s hallmark remains inclusiveness: its socio-geographic regions cater to all tastes.

There have been years where two months’ worth of rain has poured in a matter of hours, flooding tents and revellers, but few cared about the mud. The sun was usually shining the following day.

“It shouldn’t really exist, never mind succeed,” Banksy, who has created artworks for Glasto, once said. “It’s a glorious five-day rebuttal of corporatism – none of the big entertainment companies can pull off anything close. You simply cannot replicate its workforce with money – they will work only for love. The festival is an event that nobody asked for or made easy. For years, the authorities and neighbours tried to close it down. It’s an object lesson in the wilful pursuit of a dream in the face of so many enemies – a fable you can dance to.”

The first Glasto – then known as The Pilton Pop, Folk and Blues Festival – was held on September 19, 1970, the day after Jimi Hendrix’s death. Marc Bolan was one of the main attractions and the 1500 festivalgoers paid £1 apiece; the milk from Eavis’s farm was free to enjoy with the music. Word rapidly spread and by the following year, 12,000 music lovers descended on Worthy Farm. The date had been changed to the Summer Solstice, the name changed to “The Glastonbury Fair”, and David Bowie was one of the headliners.

Glasto continued evolving, attracting bigger artists each year, but the crowds, drugs, mud and rain could be hard going for the terminally urban. British critic Ben Marshall remembers the festival in the 1980s as being something “like a Syrian shanty town at the height of the civil war. The safest place was the Recovery Tent, because all the people who might have mugged you were being treated by paramedics for heroin overdoses. Now it’s lux. But it’s only since glamping was taken to the level of actually having a butler that people started calling it Glasto.”

Eavis’s own history is as fascinating as that of his festival. Sent to boarding school by his ambitious Methodist mother in order to speak “posh”, he trained as a midshipman in the merchant navy before going to sea. Returning at 19 to help his mother with the 150-acre farm when his father died, he was conscripted and made to work five days a week in a coalmine, where, he says, he learned about injustice. Each night after work, he twice milked the 60 cows to music. The milking parlour had audio; Eavis had wired a speaker to a nine-inch sewer pipe.

In essence, the contrast between being at sea in “a nice uniform and nice girls hanging around” and the rigours of rural life became the genesis of Glasto. Eavis, yearning for the reinstatement of a little glamour, became committed to sustainably changing his universe.

One minute he was cleaning out cow sheds; the next, he was onstage with Mick Jagger.

The sometimes open use of drugs, however, unnerved him. “All of these people were smoking dope and doing acid and stuff and it was slightly scary, really,” he told a journalist. “I wasn’t very comfortable with all that happening at the farm, actually. I had a Methodist upbringing, with my father being a preacher and having three or four ministers in my family. I know they were a bit old-fashioned and a bit quaint, but they were sound, d’you know what I mean?”

Being awarded the 1996 NME Godlike Genius Award, appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his services to music in 2007, and named as one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time in 2009, has had little impact; Eavis refuses to pay himself more than £60,000 a year and still attends chapel on Sunday – “a grounding thing” – preferring to focus on living a life defined by love, generosity, and tolerance than money. Glasto repaid him by grounding him when his wife Jean died in 1999, and its infinite joys and demands continue to keep him in the right frame of mind.

Chris Martin of Coldplay likens his first experience of playing there to that of Charlie entering the Chocolate Factory. “Glastonbury fills me with wonder because it’s such a peaceful place where all kinds of different people with different tastes just get along and accept each other,” he said in an interview. “It’s always seemed to me like this dream city that just appears and disappears. Glastonbury is actually still the place that I always visualise when I’m trying to write in the middle of the night. Whenever I close my eyes and think of a place where a song might sound good, it’s that triangle you see when you look out from the Pyramid Stage.”

Arguably the world’s most well-known festival venue, the triangular stage to which Martin refers, now in its third incarnation, rises from “a blind spring close to the Glastonbury Abbey/Stonehenge ley line (alignments made between landmarks and historic buildings)”. The original was constructed in 1971 from expanded metal, plastic sheeting, and scaffolding by a theatre designer briefed to create an apex that projected energy upwards while energy from the stars and sun was drawn from the heavens.

In 1981, a permanent Pyramid Stage was built; in 1994, it burned down.

Based on the Great Pyramid of Giza, the third Pyramid Stage was built in 2000. Four times the size of the original and including 4km of steel tubing — all materials and processes were approved by Greenpeace — this structure has hosted performances by some of the world’s most successful artists, among them, Joan Baez, Dame Shirley Bassey, Tony Bennett, Bjork, Johnny Cash, Tom Jones, Paul McCartney, Metallica, Pink Floyd, Radiohead, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Van Morrison, U2 and The Who.

By the 1990s, the Other Stage became the Pyramid’s alternative “mirror” stage, curated by the NME, the British independent music bible. There, indie superstars such as Blur, Iggy Pop, Massive Attack, Oasis, Portishead, Pulp, and others have given quintessential performances.

Other popular areas include the Common (sacred/ tribal/ world music), Arcadia (DJ/ EDM, featuring a huge fire-shooting mechanical spider), San Remo (Latin), BBC Music Introducing (unsigned/ undiscovered/ under the radar), Left Field (activism/ politics), Deluxe Diner / Rocket Lounge (gourmet meals), Babylon Uprising (DJ/ EDM/ trance), and queer/underground favourites, Shangri-La, NYC Downlow and Block9. Rolling Stone UK editor Cliff Joannou remembers the entire festival world changing when Glasto embraced queer. He first went in 2011 as a guest of Block9’s co-creator Gideon Berger, who, perturbed by the lack of queer visibility at British festivals, had proposed bringing in “a little gay” a few years earlier.

“Inspired by the 80s and 90s meat-packing district of New York, the club was unbridled queer hedonism,” Joannou recalls. “Dragqueens and (men) in harnesses welcomed arrivals, LGBTQ+ and allies alike. It offers a safe space where queer people could gather and dance until 6am, and where freedom of expression is celebrated. I’ve been almost every year since, and have never left the club before the lights come on. Why would I?”

Joannou still finds it difficult to express “the pride that overcame me last summer when the music stopped and over 20 drag queens, club kids, muscle boys, bears, and other glorious queerdos staged a choreographed routine to an adrenaline-charging remix of Alides Hidding’s Hollywood Seven. The memory still gives me goosebumps. Yes, the Pyramid Stage artists are incredible, but nothing fills me with more joy than walking into the NYC Downlow.”

West Holts and the Acoustic areas serve the languid and the languorous; Kidzfield and the Theatre and Circus fields cater to families; and those who love alternative music have the Field of Avalon and Green Fields.

The Ancient Futures venue in the Tipi Field, with its heartfelt celebrations of folk, global fusion and roots music, is a perennial favourite with revellers.

The Healing Field, an “Elemental Mandala” that features free Chi Gung, counselling, dance, homeopathy, massage, meditation, and yoga workshops, opens on the first day. In its Soothsayers’ Avenue are angel, astrology, palm, rune and tarot readings.

The idea behind it all? For people to learn, as Eavis said, to better support themselves and each other in the creation of “a more compassionate and sustainable planet”.

While all fans have their preferences, “the tapas Glastonbury experience” – a bit of everything – is recommended by festival staff in order to enjoy the ever-evolving wonders of the festival.

The Silver Hayes area, for example, marks its 10th anniversary this year with three new spaces: The Levels, an open air nightclub; the return of “The Wow” stage (a cult favourite); and an experimental art pavilion, The Information, a “powerful platform for urgent debate, putting forward-thinking conversation side-by-side with contemporary electronic music programming”.

And then there’s the landlocked wonder of Glastonbury-on-Sea. Designed by artist Joe Rush, who used 140 tonnes of recycled steel in its creation, this area mimics the classic British Victorian Pier experience, complete with lettered rock, pink fairy floss, and a hall of mirrors. Entertainment is provided by the animatronic One Love Robotic Band, Dick’s Cheesy Bingo, fortune telling, a Punch and Judy show, vintage slot machines, dodgems, and a helter skelter.

At Glasto, even dawn service on a Sunday takes on an entirely different meaning. The chanting of somnolent music lovers, resonant drums, and torches around the stone circle in the Sacred Space, which is situated on the crown of the site, should be on everyone’s bucket list.

John Mulvey, editor of classic British music magazine MOJO, becomes thoughtful. “Growing up in the early 80s,” he says, “Glastonbury came to symbolise a kind of ideal – a culturally and ideologically aspirational celebration in an idyllic location. It seemed like an experiment in building a better community. While that may seem naive, I could always find elements of that whenever I wandered, by the stone circle at dawn or wherever. I’m not sure if Glastonbury is the festival against which I measure all others or whether the romantic myth and rose-tinted memories have taken over, but I still think those ideals are worth aspiring to.”

Glastonbury is held from June 21 to June 25

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout