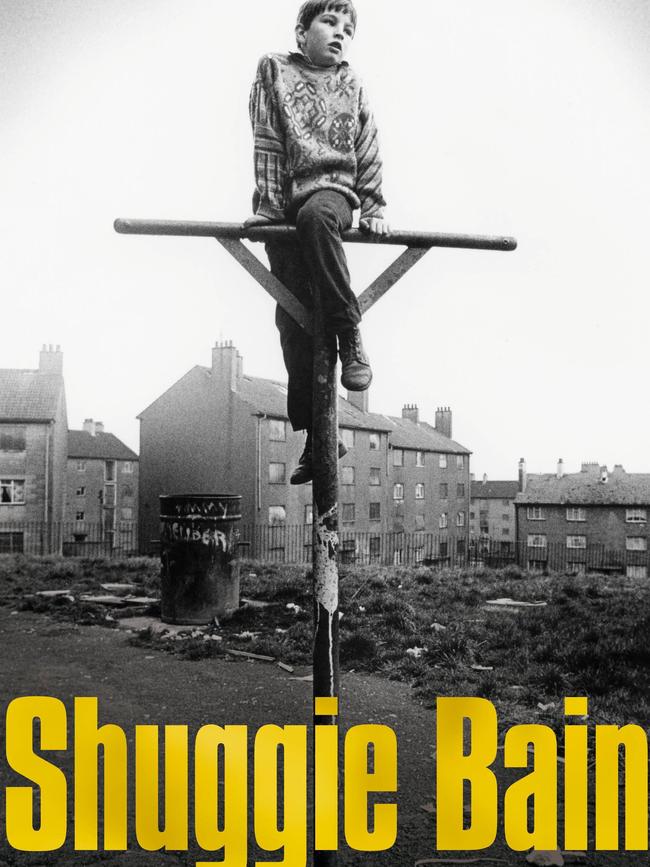

Author who grew up without books pens Booker Prize winner

Shuggie Bain, with its moving descriptions of alcoholism and poverty, is a deeply personal story.

“What good was a soft boy in a hard world?” That’s Leek (birth name Alexander) thinking about his younger half-brother Shuggie (birth name Hugh) in Douglas Stuart’s heart-wrenching debut novel Shuggie Bain (Picador, 400pp, $32.99), which won the Booker Prize on November 19. At another point, Leek, a decade older than Shuggie, tries to teach him how to walk “like a man”.

“That is the power of homophobia,” Glasgow-born, New York-based Stuart, 44, said in a recent interview. “It makes the person feel like there is something that is broken that they can fix.” He added that he, like Shuggie, grew up smothered by this feeling. Late in the novel, Shuggie realises that just as his mother, Agnes, will never not be a drunk, he will “never feel like a normal boy”.

The hard world Leek mentions is Thatcher-era Britain, where the future is not down a mine but in “technology, nuclear power and private health”. In Glasgow, where the novel is set, “the bones of the Clyde Shipworks and the Springburn Railworks lay about the city like rotted dinosaurs”. Shuggie is the titular character but the main character is his mother, Agnes. She looks a little like Elizabeth Taylor, with dark hair and green eyes. She dresses in a fur coat and keeps an immaculate house. She is also an alcoholic.

There’s a telling scene when she goes to her first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. The “fairground huckster” running the room mentions St Agnes and quotes some Latin to summarise her lament: she’s tied to the stake but the fire will not light. The woman next to Agnes leans over and whispers a clarification: “Aye, right enough. The bastards couldnae burn Saint Agnes, so they beheaded the poor lassie instead. F..ken’ men! Eh?”

That quote goes to the exhilarating Glaswegian voice that rings throughout this novel. The exchanges between Agnes and the other women on the housing estates where she and Shuggie end up are incredible to read. I must track down a Scottish friend and ask for them to be read aloud.

It also goes to the men. Here’s Agnes being comforted by two of the women, Jinty and Bridie, after she tells them her husband, Shug, a taxi driver, has left the house for the night shift. Jinty: “We wurnae born yesterday, hen. He looked to me like he was leaving for longer than that.” Bridie: “Och, never mind her. Don’t sink to her level. All we are saying is, we’ve aw got men and we’ve aw got men trouble.”

Agnes, a Catholic, left her first husband, a Catholic, for Shug (birth name Hugh), a Protestant. She brought with her two children, Leek and his older sister Catherine. Shug left his wife and four children. Shuggie is their child together. Her children are a blessing and a burden: “every single one of her children was as observant and wary as a prison warden”. It’s worth noting that Stuart, the youngest of three children, dedicates this novel to his mother.

Shug is short but handsome. He is also violent, as was his father. Stuart’s use of language creates unforgettable images. When Shug attacks Agnes, her “hardened hairspray cracked like chicken bones”. There’s a poignant moment when Agnes thinks back to when she and Shug, smelling of pine aftershave and hair pomade, first started courting and making out in his taxi: “She thought of the happy hours parked under the Anderston overpass, happy hours before they really truly knew one another.”

The novel is set in five parts: 1992 The South Side, when Shuggie is 16; 1981 Sighthill, the housing estate where the author grew up, when Shuggie is five; 1982 Pithead, another council estate; 1989 The East End; and it finishes where it started, 1992 The South Side.

Young Shuggie dresses well, has good manners and speaks properly. This means he’s a “poof” as far as the other kids and their parents are concerned. When they first enter the flat at Pithead, he comes outside, aged six, and addresses his mother: “We need to talk. I really do not think I can live here. It smells like cabbages and batteries. It’s simply impossible.”

The local women, watching as they always do, all look at him. They are amused, in an apprehensive, cruel way. “Wid ye get a load o’ that,” one screams. “Liberace is moving in!”

The core of the novel is Shuggie and his alcoholic mother. It is one of the most moving descriptions of alcoholism, and of poverty, that I have read. It’s a novel, so we can’t assume it replicates the author’s life, but there’s no doubt it’s a deeply personal story.

Stuart grew up in bookless houses. His undergraduate degree is from the Scottish College of Textiles. He moved to New York at 24 and looked for work as a fashion designer. He started this novel while working for Banana Republic, a world removed from the stealing-coins-from-the-gas-meter life he writes about. He is gay.

He is at work on a second novel, Loch Awe, set in 1990s Glasgow and centred on two young men who fall in love. It sounds like a follow-up to Shuggie Bain and if so I look forward to it. I know we’re not supposed to put books in a beauty parade, but what the heck: I think Shuggie Bain is the best Booker Prize winner since Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North in 2014.

-

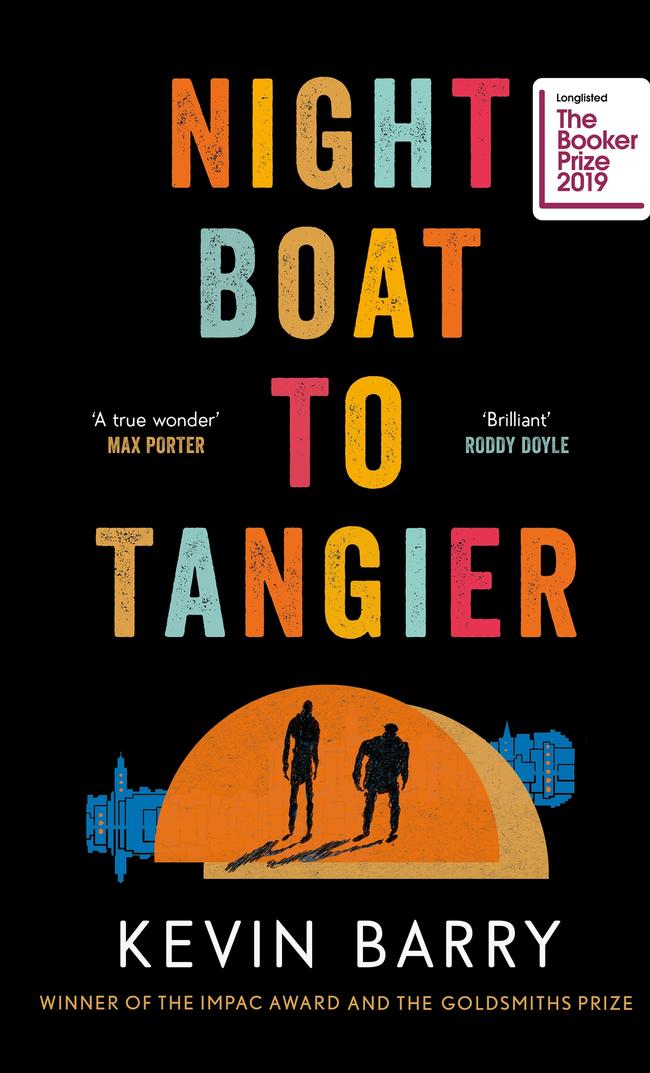

I had a few days off last week so I decided to read a book just for pleasure. Almost needless to say, once I read it I knew I had to write about it, to share it with other readers. It’s the novel Night Boat to Tangier, by Irish writer Kevin Barry, which was longlisted for last year’s Booker Prize.

I’d say it’s the most brilliantly bleak book I’ve read in a while — except that as I write this I am near the end of Douglas Stuart’s debut novel Shuggie Bain, which just won the 2020 Booker. Wow. It meets the bleak and ups the ante.

On the surface, Night Boat to Tangier (Cannongate, 224pp, $19.99) has a simple plot. Two ageing Irish gangsters, Maurice Hearne and Charlie Redmond, are loitering with intent inside the ferry terminal at the Spanish port of Algeciras. It is October 2018 and they are looking for a 23-year-old woman, Dilly, who we soon learn is the daughter Maurice hasn’t seen in three years. There’s a chance she will be on the night boat from Tangier, Morocco.

Barry, who lives in County Sligo, draws Maurice and Charlie, who are about his age, with grim humour. “They are in their low fifties. The years are rolling out like tide now. There is old weather on their faces, on the hard lines of their jaws, on the chaotic mouths. But they retain — just about — a rakish air.”

There is a lot of humour in the early pages of this tightly wound novel. There’s an echo of Roddy Doyle’s Two Pints posts on Facebook, some of which have been collected in a book. Here’s Maurice and Charlie musing on meals they regret. It starts with Charlie and sparrows.

“Greasy like John Travolta. And not a lot of atein’ on them bones, it has to be said.

“Personally speaking, Maurice? My arse isn’t right since the octopus we ate in Malaga.

“Is it saying hello to you, Charlie?”

It’s also a fair bet that Limerick-born Barry will never land a job writing for Tourism Ireland. When Maurice suggests the Hibernian fondness for drink is because “we’re a very anxious people”, Charlie responds, “Why wouldn’t we be, Moss? I mean Jesus Christ in the garden, after all we’ve been through? Dragging ourselves around that wet tormented rock on the edge of the black Atlantic …”

Yet the more we come to know Maurice and Charlie, the less there is to laugh about. “Their talk is a shield against feeling.”

When they interrogate a young backpacker, Ben, he asks them if they have given any thought to why Dilly decided to flee home. “Maurice and Charlie exchange a brace of silken grins.” It’s Charlie, Maurice’s lifelong friend (and more than that and less than that), a man who doted on Dilly, who answers. “I don’t know if you’re getting the sense of this yet, Ben. But you’re dealing with truly dreadful f..ken men here.”

How dreadful becomes clear as we move back in time, mainly the 1990s but also the early 2000s, to see how Maurice and Charlie made a lot of money. Drug dealing (and using) and other criminal activities. Charlie has a limp, Maurice has a bung eye. Maurice’s wife, Cynthia, a haunting character, becomes important.

This is a story of a missing daughter and a lost love. It’s also about how people can feel trapped, by themselves and by others. Whether we should sympathise with them is another matter. There’s a powerful extended scene where Maurice, having just had sex with a girl he met in a bar, is confronted by a “curious image”. At this point, his daughter Dilly is four.

It was the image of Gulliver pinned to the earth, the skin stretched out in a thousand sharp pulls and tacked, his wife, his child, his mother, his dead father, the green corridor, his crimes and addictions, his enemies and worse, his friends, his debtors, his sleepless nights, his violence, his jealous, his hatred, his insane f..king lust, his wants, his eight empty houses, his victims, his unnameable fears and the hammering of his heart in the dark and all the danger that moved through the night and all of his ghosts and that his ghosts demanded from him …

A chapter towards the end, The Judas Iscariot All-Night Drinking Club, set in Cork in January 2000, a little after 4am, is one of the must sustained pieces of dramatic tension I have read.

We meet, for the first and only time, people such as the barman Nelson Lavin, who knows from his swollen gums that trouble is coming, the brothel keeper Jimmy Earls, “put together like a Victorian bridge”, the former boxer Alvin Hay, who sits in a far corner and cries tearlessly, and others.

“These were fabled people. These were tricky times.” All eyes are on Maurice and Charlie, sitting at a table together, talking “low and serious”. What eventually happens explains a lot.

This short novel is close to word perfect. It was my mother who recommended it to me, even though it contains a lot of swearing, which she dislikes. I bloody well recommend it to everyone.