New York’s 1970s music scene explored by author Will Hermes

A NEW book on the mid-70s New York music scene is a remarkable work of cultural history.

WE all have cities we miss when we think of the times we spent in them. Sometimes that city can be the one you’re still living in today. But New York is a metropolis that exerts a pull on the mind even if you’ve never been there.

Whether it’s a Woody Allen film such as Manhattan or Jay Z and Alicia Keys celebrating it with Empire State of Mind, an anthem that soars against the historic wound of September 11, New York continues to occupy our memories and even our dreams.

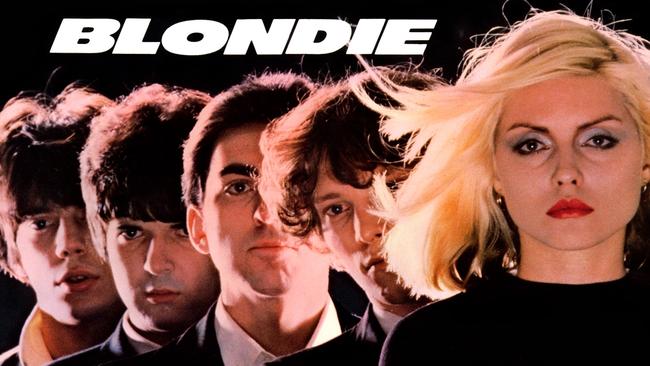

Perhaps this is why a book that explores the city’s disparate and often deeply obscure underground music scenes from 1973 to 1977 can be so vital. In the curiously — and urgently — titled Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, Will Hermes zooms in on a seemingly arbitrary period. He does so precisely because of its low standing between the glories of the 1960s and a starburst of talent that involved everyone from Blondie to Laurie Anderson and Grand Master Flash when the 80s began.

Where others saw an interim, if not a wasteland, the then teenage Hermes felt history in the making. And it’s as an historian — rather than a reportorial ingenue a la the Cameron Crowe film Almost Famous — that Hermes approaches the era now. He does so at high gear and with great anecdotal verve, unscrolling his panorama in chronological order, juxtaposing the musicians, venues, media and street life that laid down revolutionary grounds for punk, disco, hip-hop, salsa, jazz and minimalism.

Books such as Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Wont Stop (hip-hop), Tim Lawrence’s Love Saves the Day (disco) and Clinton Heylin’s From the Velvets to the Voidoids (punk) have visited this territory brilliantly before, as Hermes acknowledges. But none moved far outside of the genres they dedicated themselves to at depth, even if they had broader resonances.

Hermes tries to crosshatch all those scenes and more into one seething urban mass. It’s hard not to feel jumpy and excited while you read all about it. His New York is a place where punk bands such as the Ramones are stalking the same streets as a young taxi driver and aspiring composer named Philip Glass, while the real-life disco lovers who inspired Saturday Night Fever are clubbing the night away and Martin Scorsese films his Taxi Driver.

Graffiti tagging has just begun on the subways — “the first genuine teenage street culture since the 50s”, declares critic Richard Goldstein — and off to one side the Latino community thrills to a salsa music that penetrates the city: ‘‘Heard as a compressed radio signal blasting from shops, apartment windows, and passing cars, it sounded brassy and shrill — fun, hustling, terminally high-strung.”

Hermes is a dab hand at musical descriptions and evocative phrasing, as well as character portraits and scene-setting of epigrammatic force, not to mention the compacted foundations of his research and interviews.

He spent more than six years working on this book and has a lifetime of background experience in the city writing for journals such as Rolling Stone and Village Voice. It shows in everything from pen-stroke observations of a young Bruce Springsteen rising out of New Jersey with his “Dylan-style lyrical splatter painting” to an astute and bridging use of a Springsteen quote at the book’s end, where the Boss cites a surprising passion for the chilling synthesiser rock of Suicide: “You know, if Elvis came back from the dead, I think he would sound like (Suicide singer) Alan Vega.”

The well-documented CBGB club scene that spawned the Ramones, Patti Smith, Blondie, Talking Heads, Suicide and Television is inevitably part of this story fabric. But Hermes is equally adept at counterpointing figures such as salsa godfather Willie Colon, who depicted himself with his trombone in hand standing over a body-bag on the cover of Cosa Nuestra; or the truly mysterious adventurer Arthur Russell, who moved so fast he threatened to leave nothing behind, apart from a dazzled array of collaborators who included Allen Ginsberg, Talking Heads, Glass and the odd pioneering disco single and unreleased avant-garde recording.

Hermes details how legendary record producer John Hammond told him he would be remembered as the man who discovered Billie Holiday, Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Russell. Without saying more, Hermes implies something tragic in this anecdote, a fleetness and restraint he applies with skill across the book.

By keeping a tight focus on time and place, Hermes sustains a momentum that made me think of Love Goes to Buildings on Fire as a rock ’n’ roll 24. Keeping in mind the television series parallel, it’s New York that emerges as the story’s agent Jack Bauer, the central character, with various musical genres washing over it like so many waves of drama and personality as the clock races to the end. An epilogue brings everything into the present with the type of elegiac, scene-panning technique we’re used to experiencing at the close of great TV shows.

Hermes is similarly excellent at splicing wider events into his story like a news ticker stream, from the night of the New York blackout to the Son of Sam serial killer and the astonishing amount of fires lit to cash in on insurance scams and burn down buildings that paved the way for developers. He details how, in 1975, protesting police and fire unions employed a publicity firm to hand out leaflets to visitors at airports and bus terminals: “On the cover was a shrouded skull beneath the words, ‘Welcome to Fear City’.” With incidents such as that in mind, it is easy for Hermes to make wry, zeitgeist references to Charles Bronson being well-received in the film Death Wish as an architect “turned vigilante” who goes “in search of muggers and guns them down”.

Of course, this book won’t be for everybody. It’s for music junkies all the way. If you’re one of those, you will likely recognise the title as a reference to Talking Heads’s first single. Trainspotters may even claim they know most of this stuff already, but it’s Hermes’s ability to connect the dots that puts him above geeky details. Flying his own flag indirectly, Hermes describes Talking Heads: 77, a self-titled and numerically ominous debut, as “the sound of panic attack massaged into a way of life”.

Let’s face it: most contemporary music books are junk, lucky to be read a year after being published. Popular music, rock ’n’ roll, street culture, it just don’t get no respect. The best one can hope for is the stock-in-trade approach that most of these histories and hagiographies depend on: blow-by-blow summaries, cut-and-paste with oral accounts.

What Hermes wants to do with the gyroscopic intensity of his prose is glue you into the time and the place, to make you live in New York in the 70s. The task must have seemed daunting, if not foolhardy, when he began. The decision to write things up as a fuse-burning, jump-cut narrative is only one example of his ambition.

Here and there he includes autobiographical moments about being a teenager in suburban Queens, making forays into Manhattan to see the rock group Television blow his mind amid the towering guitar lattices of Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd. An apocryphal tale of Jimi Hendrix spilling tears over the hands of the young Richard Lloyd as the master taught him guitar serves just as well for Hermes’s own baptism in the musical grit of the 70s.

It’s only a coincidence that Hermes’s surname echoes that of the mythical Greek messenger of the gods. But you feel by book’s end that it’s an appropriate handle.

Not all his personal asides work, but they are used sparsely and give the book an added affection, a sense that we are hearing a story told up close. An underlying one-shot energy drives it forward, as if Hermes was latently aware he might not get a chance like this again.

Inevitably, it all gets too jumpy and crowded sometimes, with moments and characters dropped rather than evolved, but Hermes does his best to return and give them what they deserve.

That said, one feels the book has been ruthlessly edited at 368 pages, and that another 50 might have opened out blunter edges and muted characterisations into a deeper and more involving story.

Beyond that, something double in size seems possible: a cultural history of Dostoyevskian scope. It’s no accident that in the wake of this book Hermes has just been signed to write the authorised biography of Lou Reed.

Mark Mordue is an author and critic. He is at work on a biography of Nick Cave.

Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever

By Will Hermes

Viking, 384pp, $29.99