New graphic novels by comic creators Dylan Horrocks, Scott McCloud

Two acclaimed comic creators tackle life’s thorny issues in their new graphic novels.

What responsibilities do artists have to their art and audience? Two recent graphic novels gamely wrestle with these and related thorny issues with great gusto and flair. They also break a long drought of major fictional work by two acclaimed comics creators, making their synchronous publication double cause for celebration. And though they may share certain themes and display a passion for and mastery of the medium, Scott McCloud’s The Sculptor and Dylan Horrocks’s Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen stake out very different territory.

McCloud is perhaps best known for his landmark nonfiction trilogy — Understanding Comics, Reinventing Comics and Making Comics — which interrogates the medium’s lineage, decodes its language, peers into its digital future and deconstructs the creative process, all in comic strip form. These insightful, engaging works made the esoteric accessible to enthusiasts, practitioners and laypeople alike.

But McCloud is more than a theorist and teacher. He first came to notice with the delightful, gently subversive 1980s-90s manga-inflected sci-fi series Zot!, followed by the satirical cautionary tale The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln in 1998. More than a decade later, The Sculptor proves he can still walk the walk, even though he falters at the end.

David Smith is a young, self-absorbed and impatiently ambitious sculptor, who has hit a creative wall after being dumped by his benefactor, and is short on funds, friends and family. While brooding over his unfulfilled life in a Manhattan diner he’s joined by the Grim Reaper in the guise of his long deceased Uncle Harry, who lays out two paths for David.

He could lead an average, contented life, or he could be granted the ability to mould anything with his bare hands. The catch? If he opts for the latter, his life will end in 200 days. With little to live for except his art, David leaps at the chance to create something truly extraordinary that will leave his mark on the world.

However, life ambushes him in the form of Meg, an aspiring actor and angel of mercy who brings him hope, inspiration and finally love, but also carries serious baggage of her own. Forbidden to reveal his new super power to anyone, David sculpts the city in secret, becoming a Banksy-like figure, albeit one who does more permanent damage, incurring the wrath of the authorities. Yet, despite his remarkable gift and with real life making ever greater demands on his precious time, his sculptures are more provocative than pure and his sublime artistic statement remains elusive. All the while, the clock is ticking.

For most of its length, The Sculptor is a finely crafted and immersive read. McCloud elegantly deploys every trick in his comics toolkit to relate a poignant, contemporary fable, occasionally marred by some clunky dialogue that detracts from a largely smart, acerbic script, and a climax that strives for the transcendent but slips into the trite. Thankfully it doesn’t overshadow the author’s greater achievement with the book.

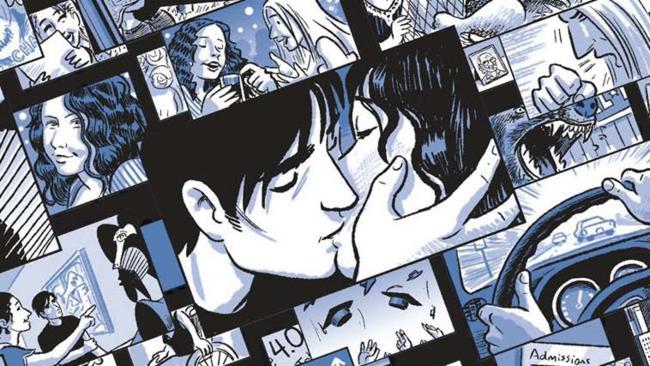

McCloud brings a compelling complexity and delicacy to his characters, his world and his storytelling. Time is at the heart of the narrative, and McCloud sculpts time like a dream: compressing, stretching and splintering it, creating parallel and split time streams, carefully capturing tiny instants and grand gestures, and filtering and focusing attention to make every moment count. And his restrained artwork, with its scratchy, cartoonish naturalism and muted monochrome hues, establishes a quiet intimacy with the reader; you almost feel like you’re eavesdropping on David’s life.

While The Sculptor torments its protagonist with an invidious choice, echoing WB Yeats’s quandary about perfecting the life or the work, the great poet’s contention that “in dreams begins responsibility” haunts the eponymous hero of Horrocks’s altogether more exuberant Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen. On the opening page, Yeats’s assertion is placed in clear opposition to feminist educator and porn director Nina Hartley’s insistence that “desire has no morality”, and through the course of the book Horrocks uneasily navigates between these contradictory positions, seeking some resolution.

The Magic Pen is a metafictional jeu d’esprit, a buoyant, erotic meditation on the magic of comics, the dangerously liberating power of fantasy and a journey through the conflicted psyche of its author. It is in many ways a spiritual sequel to Auckland-born Horrocks’s celebrated Hicksville, a dazzling ode to the medium’s past and potentia that constructs an imaginary, utopian and remote safe harbour for the world’s comics in New Zealand. In this new book he dives into altogether more troubled waters.

The story opens with Sam Zabel suffering from serious cartoonist’s block. Forced to write superhero comic books to pay the bills, he hasn’t worked on a personal project for years, and now he can’t even finish his hack work.

Seeking solace in online Arcadian fantasies, his own creation, Lady Night, invades his reverie to question his talent, self-pity and repressed feelings. At his lowest ebb he bumps into Alice, a geeky, feminist web-cartoonist who mentions a mysterious old New Zealand comic, The King of Mars, that piques Sam’s curiosity.

Locating a second-hand copy, Sam accidentally sneezes on a page and — in a neat homage to Winsor McCay’s classic 1900s newspaper strip Little Sammy Sneeze — disrupts reality. Transported into the comic, he becomes stranded on Mars, where he is mistaken by the locals as their prodigal cartoonist god king and must face all manner of hazards and temptations, from rampaging monsters to the carnal needs of his long neglected Venusian wives.

Coming to his rescue and guiding him through this comic kingdom, and worlds beyond, is the plucky, jet-booted manga schoolgirl Miki, who tells him of a fabled magic pen “that grants its users their heart’s desire”. The pen was used to create The King of Mars and other ‘‘sacred’’ comics tucked away in Miki’s satchel, and Sam, like the reader, learns how to traverse these stories within stories by giving them the breath of life.

Hoping the pen may help him get his creative mojo back, Sam, alongside fellow travellers Alice and Miki, plunges headlong through a multiverse of comic genres, tropes and intersecting realities, to track it down. During their Mobius strip-like quest, which whisks them back to the unsullied dawn of graphic story- making and deep into the toxic recesses of violent male delusions, our adventurers are forced to confront their shifting attitudes to fantasy, representation and self-censorship. And, like the best stage enchantment, the inky talisman turns out to be artful misdirection, behind which Sam’s creative coming of (middle) age plays out.

If at times Sam is frustratingly passive in his own story and the characters are given to clumsily voicing their creator’s ruminations on the pleasures, perils and social consequences of unfettered fantasy, there’s no denying Horrocks’s sincerity in placing himself at the centre of this dilemma. Fortunately he does so with good humour, ingenuity and an infectious sense of wonder, ably served by a lean, loose Tintin-esque line and sparkling storytelling.

Despite occasional heavy-handedness, The Sculptor and Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen show McCloud and Horrocks at the top of their game, tackling weighty, contentious ideas with finesse, candour and wit.

Cefn Ridout is a commentator on graphic novels and comic book writer and editor.

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen

By Dylan Horrocks

Fantagraphics, 228pp, $29.99

The Sculptor

By Scott McCloud

First Second, 496pp, $35.95 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout