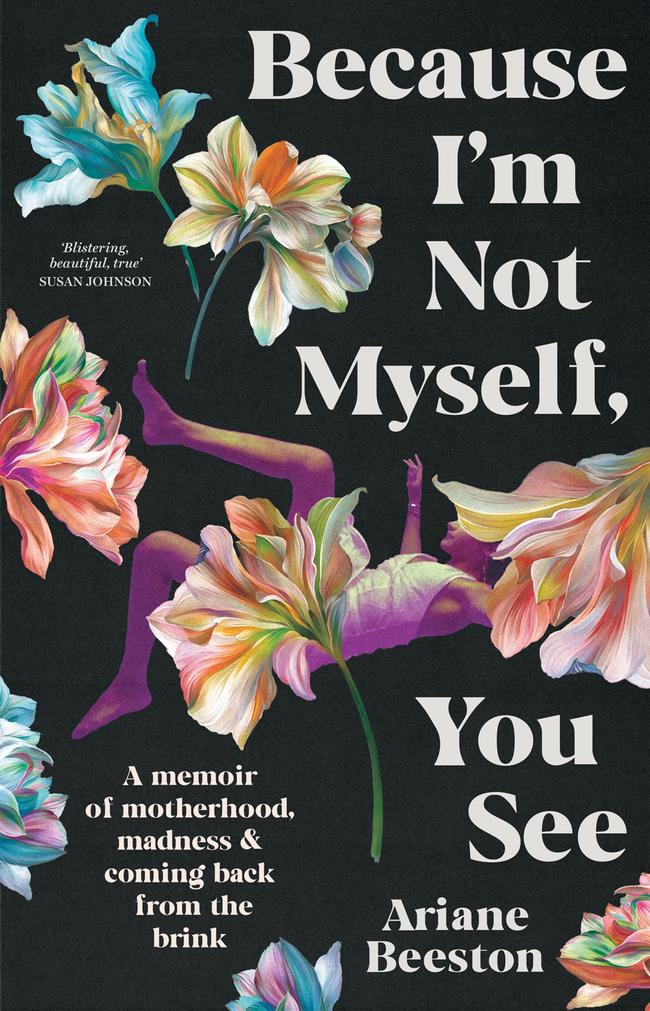

My life as a haunted new mother

As a child protection worker and psychologist, young mother Ariane Beeston never thought she would be the one who needed care. Until she was.

I’m on my way home from work when my baby turns into a dragon. We are standing at the lights of a busy intersection, waiting to cross the road. This is not the first time it’s happened. I’ve seen dragons before – in the cot, the swings, the highchair. But this one is angry and fierce and red. This dragon is different.

The woman standing next to us smiles at him, leans in to take a closer look. I snap the lid of the pram down and angle the wheels away from her. I must protect my baby from prying eyes. It’s hard to know who to trust.

I turn off the main road, pushing the pram along the narrow backstreets. There’s a squeal from under the hood, a squeal that settles somewhere in my spine. When I lift the lid back up, the dragon is gone. My baby, Henry, beams at me, all cheeks and blue eyes.

“Nearly home, buddy,” I tell him.

My feet ache in the high heels I wore to the office. It’s my third week after maternity leave, and I am back at the Department of Community Services, where I am a child protection worker, in one of the busiest and most chaotic departments in Australia.

It’s dark now and cold – a clear July night. The stars peek through one by one. When I look down, I can see that my hands are attached to me, but they’re no longer mine. I inspect them like a scientist – they’re at the end of my arms, my rings are all there. But they don’t belong to me.

I call my psychiatrist, Dr Q. The hands still work. She picks up straight away. I’ve never called her between sessions before. “I don’t think my hands are mine anymore,” I tell her. “I don’t think they’re mine.”

“How scary,” she says. “Where are you, Ariane? Is Henry with you?”

“Yes,” I say. “But he’s a dragon again. We’re on our way back from daycare.”

“Where’s Robb?” Robb is my husband. “He’s away,” I say. “For work. LA maybe? Or Singapore? I think he’s in LA.”

I keep pushing the pram, placing one wobbly heel in front of the other. Henry points at the neighbour’s cat.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” I say. “But I just don’t feel right.”

“I know,” Dr Q says. And I know she does.

“I’m so tired.”

“You’re doing so well,” Dr Q says. “I’m going to stay with you, okay? Until you get home. Just keep walking.”

I want to curl up in her voice and sleep and sleep and sleep.

“It’s bad, isn’t it? It’s really bad.” I snap a photo of the baby’s bare bottom and send it to Robb, who’s at work. It’s the third photo I’ve sent that morning and I’m feeling increasingly panicked. I’ve been rubbing thick white Sudocrem onto the rash for hours but it’s still angry and red. It seems to be spreading.

The baby looks up at me with navy-blue eyes I don’t recognise. My own eyes are brown – I thought his would be too. Did I take the right one home? How often do babies get mixed at birth? They’re coming for him, I know. The nappy rash is so bad, DoCS are going to take him and everyone will know what a terrible, terrible failure of a mother I am.

They know. They can see it. I feel as though I might vomit.

I rub more Sudocrem onto the rash and send Robb another photo.

“Does this look bad?” I ask again. “Is it getting worse?”

“No,” he replies. “It looks fine to me. But why don’t you ask your dad (my father is a GP) if you’re worried? I’m going into another meeting. I’ll call you later. I’ll be home early.”

I don’t ask my father; instead, I text my mother.

“Oh yes, babies get nappy rash,” my mum says. “Poor thing. How’s he feeding? Did you get much sleep last night?”

“He wakes every 45 minutes,” I say. “I can’t see straight.”

“I remember those days,” she says. “I don’t think you sleep properly for two years.”

Babies get nappy rash, I tell myself. Babies get nappy rash. Babies get nappy rash. Yeah, and they get removed.

■ ■ ■

At 3.45am I google: Can you die from lack of sleep? I am certain there is something wrong with the baby, something I don’t know how to articulate. I can’t make out his features. I look at his nose and the rest of his face is out of focus. There is no “whole”, only parts. I could be looking after someone else’s child. Sometimes I wonder if I am. Sometimes I wonder when his mother is coming to get him.

■ ■ ■

“Henry is so cute, Arns,” Brooke tells me one evening, when she drops by after work. I have stopped letting people come over – I must protect the baby from prying eyes – but I have made an exception for Brooke. Robb is overseas again. She pushes the pram for me while we walk around the streets of Redfern, lined with scruffy terraces and large council bins. Brooke’s friend has just had a baby and she tells me how “funny looking” he is.

“It’s weird,” she says. “And this is mean, I know. Both parents are attractive, too. But he looks like a grumpy old man. Henry is super cute, though.”

I look down into the pram, into the mess of features in front of me, and back at her. The baby’s not a dragon today, but he still doesn’t look right somehow.

“It’s okay,” I snap at Brooke. “You don’t have to lie to me.” I take the pram from her, trying not to show how angry I am. “I know he’s not cute,” I say. “You of all people don’t have to pretend.” I am so tired of having to pretend when everyone around me is lying. Why am I the only one trying to protect him? Brooke laughs, then stops and stares at me.

“Wait, you’re being serious?” she says. She looks down at the baby, then back up at me. We keep walking towards the house. “Arns,” she says, her voice lower than usual, “do you think it’s weird you don’t think your own baby is cute?”

“‘I don’t know,” I tell her.

My voice is a challenge. What would she know? “Is it?”

In her incredible novel Nightbitch, a book I’ve returned to again and again, Rachel Yoder describes the intense isolation of new motherhood. The loneliness of her main character, whom we know as Nightbitch, feels almost tangible, “as if it were her second child”.

In one scene Nightbitch describes a group of mothers with their bagged snacks, sniffing nappies and running after children with tissues. There’s a look, she continues, that all mothers have – a combination of boredom, exhaustion and grief for what and who they’ve lost. Nightbitch actively avoids making mum friends because although she’s a mum, she’s not that kind of mum.

Most local mothers’ groups bring vulnerable women together based on their postcode and their child’s date of birth. But while nothing bonds women faster than sharing birth stories (while still bleeding and leaking and reeling), there’s often an element of performance when meeting new people – and particularly so as a new mother. There’s a level of loneliness about this that I couldn’t quite articulate until years later. “This is not who I am,” I wanted to tell the other mums when I managed to drag myself to Redfern Park, where we’d sit on rugs under the shadows of the trees. “You didn’t know me before and this version of me isn’t really me but it’s the only me left over. I am not myself, you see.”

■ ■ ■

It occurs to me as I’m out walking one afternoon, pushing the pram around and around and around, that I don’t actually exist. I am dead. I have already died. If I don’t actually exist, then it won’t matter if I kill myself, because you can’t kill something that never existed. And if I am already dead, then no one will miss me.

It feels as though I have solved some great puzzle of life and death – all the pieces of existence have fallen into place. I am calm. I am so very calm. Around and around and around and around and around and around and around.

■ ■ ■

“Don’t Trust Your Tired Self,” flashes the sign above a busy intersection. It’s a NSW government campaign warning of the dangers of driving while fatigued. “Being awake for 17 hours or more has a similar effect on your driving as a blood-alcohol content of 0.05.” And yet, I think, we ask mothers to mother – to keep another little person alive.

Don’t Trust Your Tired Self.

Don’t Trust Your Self.

You’re Tired.

■ ■ ■

I am convinced the baby doesn’t like me. I am not bonding with him, and he isn’t developing an attachment to me either. He is better off without me. Everyone is better off without me. He is better off without me. Everyone is better off without me. Without me, without me, without me. Ruminate: from the Latin ruminatus, past participle of ruminare, “to chew the cud” …

Just walk into the traffic.

We are standing at the lights of a busy inner-city intersection, waiting to cross the road. The pram wheels are on the ramp, primed. Traffic is tearing past and I clasp the handle. My fingernails leave crescents in both palms.

■ ■ ■ ■

This part is hard to write. As I sit in front of my laptop and try to find the words, I am simultaneously standing on the threshold of the psychiatric unit at the hospital, 20 minutes from my home. I am at the head of the long corridor lined with patients’ rooms. My stomach is a closed fist. Even now there is shame. Even now – 11 years on – there is guilt that my son’s first year of life involved a psychiatric ward.

Shall we walk down the corridor together? Shall we open the door to this room I’ve kept closed for many years now?

Yes. I think it’s time.

This is an edited extract from Because I’m Not Myself, You See: A Memoir of Motherhood, Madness and Coming Back From the Brink by Ariane Beeston.

Lifeline: 131114.

Ariane Beeston is a child protection worker and registered psychologist when she gives birth to her first child, and quickly begins to experience scary breaks with reality. Out of fear and shame, she keeps her delusions and hallucinations secret, before being admitted to a mother and baby psychiatric unit, where the psychologist is forced to learn how to be the patient. This is her first book.