My father dragged us to Moscow during the Cold War. It was years before we got out

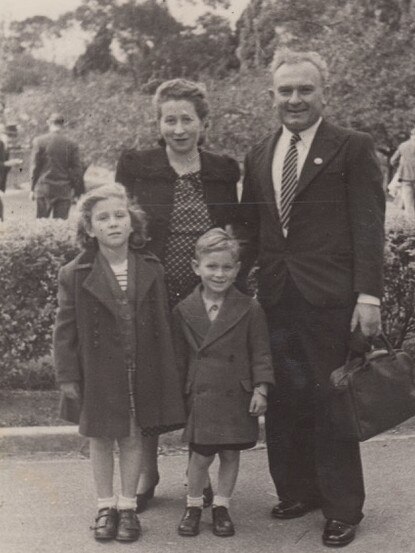

In 1956, reporters gathered in Port Melbourne to interview our family before we sailed for the Soviet Union. It was most unusual for Russians or even local Communist ‘true believers’ to go to live in the USSR. Little did we know the trauma and struggle that lay ahead.

On May 7, 1956, reporters and photographers gathered aboard Orcades at Port Melbourne to interview our family before we sailed for the Soviet Union. At the time, many migrants were arriving in Australia; it was most unusual for Russians or even local Communist “true believers” to go to live in the USSR.

Little did we know in May 1956, that it would take seven years of trauma and struggle to return to Australia and reunite our family in Melbourne.

Sometimes it is the minor, unknown figures who can reveal much about the political culture and policies of both the Australian and Soviet governments during the Cold War. Although these governments were often depicted in ideological terms as being opposites, both shared many common features: mutual ignorance of one another’s society and conservative, slothful, and compassionless decision-making.

Our family was subjected to the prejudices, suspicions and misinformation generated by Cold War politics.

Apart from Soviet bureaucrats, our future would be determined directly and personally by Prime Minister Robert Menzies, the Director-General of ASIO Brigadier Charles Spry, Minister for Immigration, Alexander Downer senior, Minister for External Affairs, R. G. Casey and future Prime Minister, John Gorton, in conjunction with Secretaries and Deputy Secretaries of their departments and leading Australian and British diplomats in Moscow.

My father, Abraham Frankel, was born in Kerch, Crimea in 1908 and left Russia in 1921 amid civil war and starvation. Dad’s older married sister remained, while he and his parents and two brothers went to Palestine and settled in Tel Aviv. Here, my father became an idealistic Communist anti-Zionist during the 1920s and 1930s and campaigned for the creation of an equal Jewish/Arab Palestinian society. With increased violence and unemployment in Palestine, he departed for Perth in 1938 and moved to Melbourne in 1940. Dad threw himself into all kinds of political activity and also acted in the Yiddish Kadimah Theatre in North Carlton.

My mother, Tania Lubitsch, was born in Grodno which was part of Poland from 1920 until 1939. Her father died when she was eight years old and her mother, two brothers and grandmother lived in dire poverty. Having survived nearly being killed in a pogrom in 1935, at age 17, Tania escaped poverty and death due to her aunt and uncle in Melbourne paying for her fare to Australia. Arriving in Melbourne in 1937, my mother was the only member of her family to survive the Nazi holocaust.

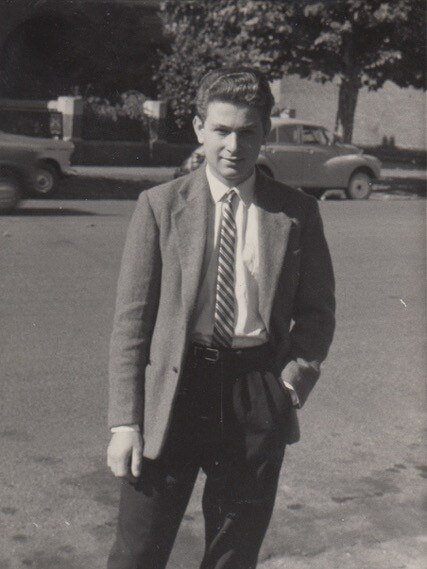

Both my parents were self-educated working-class Communists and worked in various factories. They were active in Communist politics and cultural organisations and met in 1940 after Mum saw Dad perform at the Kadimah. After getting married in December 1941, they built a life in the thriving left-Jewish ghetto of North Carlton. My sister Genia was born in 1943 and I in 1945.

Our house was full of East European émigrés, bohemians and Communists discussing literature, politics, and music. Actors, writers and musicians who either played in New Theatre productions or were associated with Realist Writers were close friends. Dad was active in the Australia-Soviet Friendship Society where he taught Russian language classes. He also hosted Soviet film screenings at the Carlton Theatre from the late 1940s until we left for Russia in 1956.

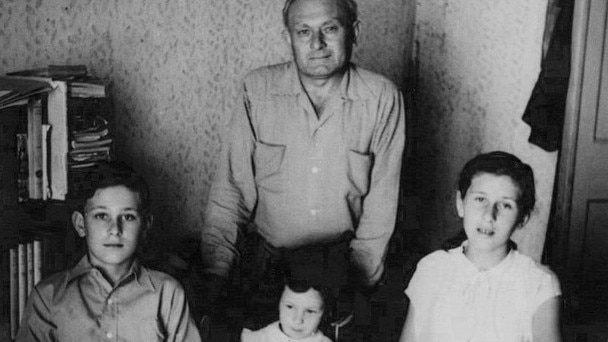

Due to Dad’s inadequate wage, we were evicted from our rented house in December 1950. With the help of my mother’s relatives, we rented a house in East St. Kilda. Genia and I attended the local school in St. Kilda and my sister Maya was born in 1954. Our childhood years in St. Kilda were incredibly happy despite the politics of the Cold War impacting our family.

The late 1940s and 1950s were years of growing hostility to Communists and fellow travellers. My parents were monitored by ASIO due to Dad’s politics and helping several displaced, lonely ex-Soviet men return home. ASIO labelled him a “subversive” for supposedly undermining Australia’s immigration program. An ASIO report also regarded Genia and I as “subversives” for “telling other children in the street that there is no God, no Father Christmas, no fairies and that Russia is the best place to live”.

My parents entertained Soviet Embassy officials in our Carlton and St. Kilda homes. The most notorious Embassy official was Vladimir Petrov who visited us three times in 1952. I remember Petrov as the “nice man” who gave me a box of chocolates. While I saw him eating and drinking with other guests, like my parents, I had little knowledge that this lazy drunkard would become ASIO’s prize catch.

Most Australians were unaware that Petrov was a badly-behaved alcoholic chasing women in his underpants. In November 1956, his behaviour became public knowledge following his arrest in Surfers Paradise minus his trousers after a drunken brawl.

Most people feared being called to appear before the Royal Commission on Espionage that was set up by Menzies in 1954. Not my outspoken father. Despite Petrov informing ASIO that my father was never considered for espionage work, ASIO officers interrogated him at our home in November 1954. Dad called Petrov a rat, a drunkard, and a traitor. This interview was extraordinary for Dad’s defiance of ASIO’s assumption that any Communist, social reformer, supporter of the peace movement, or East European migrant was a potential or actual spy or subversive. We paid a high price for Dad’s principled stand. ASIO would use this interview in later years to brand him “a danger to national security” who should not be let back into Australia.

My father was a fanatical true believer in the Soviet “workers state” and had long applied to return to Russia. His entry visa was granted at the end of 1955, and we departed Melbourne in May 1956 before full knowledge of Khrushchev’s “secret speech” denouncing Stalin was published in Western media in June 1956. Mum did not want to leave Melbourne and pleaded with Dad not to go. Her desire to keep the family together forced her hand and she reluctantly agreed to join him.

Beginning with our arrival in Leningrad and on our long journey to Baku to live with Dad’s sister, we encountered one shock after another. Dad’s idealistic vision of Soviet life was quickly shattered. We arrived in a country still suffering from the trauma of decades of repression and a war that had killed tens of millions and destroyed twenty thousand cities, towns, and villages. Finding even a room was extremely difficult. In Baku, Dad’s sister could not accommodate us, and one could not find work without a place to live. We left for Kerch and eventually found a room without a kitchen or running water. It was built by German prisoners of war in a new industrial settlement called Arshintsevo on the Kerch Strait. This was the real Soviet Union closed to tourists. Local Soviet officials could not believe that anybody would want to come to live in Kerch.

In this grim room, our family pledged to get out of the country as soon as possible. Dad cried and cursed his blindness and naivety for believing Soviet propaganda for decades. Back in Melbourne, an informer continued to feed ASIO with blatant lies. Dad was supposedly now a “privileged big shot” working in submarines or touring the country giving lectures. Instead, my father worked as a low-paid welder in a factory under shocking conditions. Mum became depressed and refused to leave our tiny apartment. Maya was a toddler and Genia and I demanded to be allowed to return to Australia. As part of a strategy devised with Dad and Mum, we refused to go to school.

Luckily, we arrived in Khrushchev’s “thaw” characterised by underground political humour and authoritarianism rather than Stalin’s terror. We witnessed all the harshness of Soviet life in the raw – scarcity of food and goods, alcoholism, corruption, and domestic violence. The system was a shambolic mockery of socialist values. We were forcibly isolated from the outside world and experienced setbacks and interrogations. After struggling to get the Soviets to let us out, we found that ASIO had vetoed our return. Through a series of dramatic setbacks, interrogations and plot twists that would make a cinematic thriller, we three Australian-born children and our mother eventually returned to Australia in 1960, but not Dad.

In Melbourne, we campaigned strenuously to change the government’s mind. It took three long years to overcome ASIO’s opposition to Dad being able to join us. In 1963, he returned a politically shattered man and only lived another five years. We, however, learned much from experiencing Soviet life and our struggles against Soviet and Australian bureaucracy. It was an invaluable sociopolitical education. This is a story of memory and forgetting, of civil war, annihilation, and political fanaticism. Yet, it is not just a tale of dreams and deceptions. Importantly, it is also about love and courage in the face of concerted opposition by the Australian and Soviet governments. No one else from Australia went through the experiences suffered by our family.

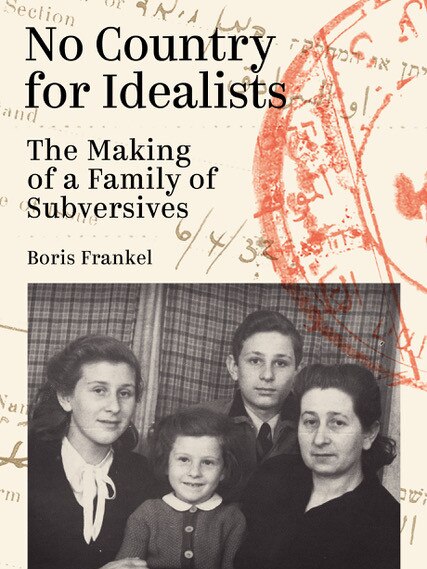

No Country For Idealists: The Making of a Family of Subversives, published by Greenmeadows, 386pp, $34.99.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Professor Boris Frankel is an Honorary Principal Fellow at the University of Melbourne. He is a social and environmental theorist and political economist whose work has been translated into many languages in Europe, Asia and Latin America.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout