Muriel’s Wedding: PJ Hogan gets musical

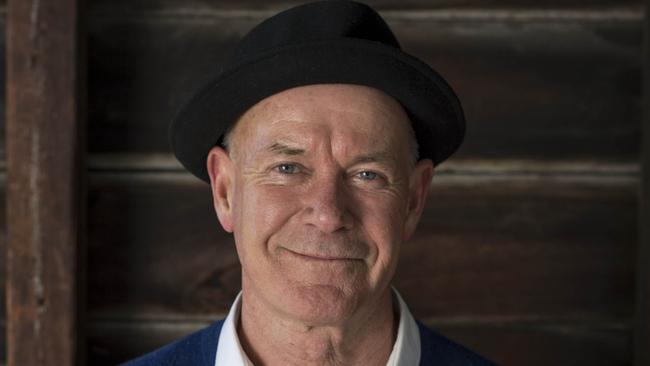

Muriel’s Wedding was a career-defining triumph for writer-director PJ Hogan. Here he tells of turning it into a musical.

SEPTEMBER 27: Today is the first read-through of the book and score with full cast. Despite four years (on and off) of development and at least six workshops, I feel like I’m about to sit for my HSC exams and I haven’t studied enough. Only Simon Phillips, our director, seems unfazed.

As usual Simon is dressed all in black (which must be one less decision for him to make each day) with the exception of his socks, which are always some kind of zesty mismatched colour. I know this because Simon never wears shoes in the rehearsal room. I’ve begun to wonder if the socks might be some sort of subconscious indication of how the production is going, a colour-coded thermometer taking the show’s daily temperature. Today’s socks are a Mikado yellow and Crayola blue. Let the table read begin. Two hours later: table read ends. Oh, god. Well, all I can say is that it sounded much better when I read it aloud to myself at home.

SEPTEMBER 29: The first few days are devoted to learning the songs. Each morning begins with vocal warm-ups and the room is filled with voices trilling up and down the scales. Kate Miller-Heidke, who was classically trained, whispers to me: “In the opera world everybody comes having already done their warm-ups — you don’t get your hand held like this.” I instantly imagine opera singers as an elite commando regiment and our musical theatre folk as some kind of wimpy army reserve.

SEPTEMBER 30: God, I’m the writer again. I forgot how much I hate, hate, hate being the writer. I haven’t been the writer on a production since my early 20s. In film it usually means better seen but not heard and in TV (at least in Australia where I got my start) it means being neither seen nor heard. Writers in the theatre have it a little better. I’d describe it as being seen and heard as long you are discreet about it (this applies to all writers except for Edward Albee, who persists on being heard even a year after his death). It took me a long time to work up the courage to call myself a director. Directors always seemed to me, well, older and exuding an air of authority that I didn’t think I’d ever have. In my TV years the (mostly male) directors were father figures or cool hipsters who seemed clued in to how the world really worked. But then I saw how they botched my script and I realised that exuding authority and looking cool was the least important weapon in the director’s armoury.

As Rupert Everett once said about one witty, charming but utterly incompetent director, “He gives good set.” But giving good set doesn’t mean a thing if you have no vision for the work. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen a cast and crew emerge utterly dispirited from a theatre having just seen the film they’d had such a great time making. When I decided to direct my own stuff it wasn’t that I thought I could do it better, I just knew I couldn’t be worse.

OCTOBER 1: Simon’s socks today are a melancholy yellow and a somewhat wan pink. The day seems to follow suit and everything is very lacklustre. By the afternoon I am so depressed I want to tear Simon’s Cassandra-like socks from his feet. I am probably spending too much time thinking about Simon’s socks.

OCTOBER 2: Choreographer Andy Hallsworth is working on the opening number, Sunshine State of Mind, the song that sets up Muriel’s home town of Porpoise Spit. The ensemble swings around surfboards like they are in an old Annette Funicello movie. Ideally the surfboards should be made of foam but, since the production is strapped for money, they are real. The number is bouncy and fun but in the back of my mind is the fear that one day one of those boards will fly out of a sweaty pair of hands and impale somebody in the audience.

But the danger turns out to come from a more unexpected quarter: as the cast dances into the next scene’s wedding reception, Tania the bride whacks one of the guests in the face with her bouquet.

I am learning many new words: the script isn’t a script, for some reason it is called The Book. Which makes me feel very important. I am no mere script writer now, I am the author of The Book. Still, I can’t bring myself to refer to it as The Book. When I try I always stammer on the first consonant as in, “Simon, on page 27 of the … b … b … b …” — and then, shamefully whispered — “book …” To which Simon (magenta and gold socks) replies “Stop worrying about (confidently shouted) THE BOOK! THE BOOK is fine. Worry about act two — it’s longer than My Fair Lady!”

And, though not technically a word, “magic of theatre” is said a lot, usually as a noun, as in: “Simon, in this moment in the film, I cut to Muriel in a close-up, which brought the audience close to her; how will you create that moment of intimacy when she’s standing in the middle of a crowd, in the middle of the stage, in the middle of a song?” “Magic of theatre!” booms Simon. I subsequently discover “magic of theatre” means a lighting change, usually a dimming of the main lights while a spotlight picks out the character who, in a film, would be in a close-up.

OCTOBER 5: Still on Tania’s wedding reception. “Some of you are getting a bit opera with your glasses,” calls Andy, holding a champagne glass high over his head as if it were the Olympic torch. “It’s a wedding, not the first act of La Traviata.”

I learn another new word: shapes. It seems that staging a musical is a hunt for “shapes”. “That’s a nice shape,” says Simon, standing on a chair, his back against the wall, observing the placement of the cast. In his choreography, Andy is often searching for the right “shape”. When a scene is out of shape it is not unfit, just unfocused. Actors are constantly moved around the stage until something shapely is achieved, which will be (I guess subconsciously) pleasing to an audience.

OCTOBER 6: After she’s arrested at Tania’s wedding (for wearing a stolen dress), Muriel sits in her bedroom and sings ABBA’s Dancing Queen, her favourite song. In the next room Muriel’s dad, Bill the Battler, is trying to coerce the cops into letting her go. Both rooms are visible on stage and, when Muriel starts to sing, Bill must deliver his lines in the musical spaces between her lyrics.

Gary Sweet, who is playing Bill, is finding this difficult. He either talks over Muriel’s lyrics or forgets to say his lines altogether. Musicals by definition require a certain amount of stylisation no matter how realistic the source material may be. But after years of saving people and looking concerned in Police Rescue, Gary is finding realism a tough habit to shake. “It’s hard waiting to say my lines between all these lyrics,” he groans. “Yes, I know, Gary,” replies Simon (maroon and peach socks, the colours of infinite patience), “being an actor is hard.”

OCTOBER 7: Simon is working on an especially difficult scene for the actors. Actually, the show is full of difficult scenes, since we’re trying to maintain the emotional impact of the movie. At moments like this it’s hard for me to keep quiet since I think I already have the answers, having directed the original. It’s then I have to remind myself that: 1) You are NOT the director (and just as well, as you have no talent for shapes, and possibly no talent); and 2) This is only the second week of a five-week rehearsal.

As Andy patiently explains to me: “First comes the chory (choreography), then come the shapes, then the acting, then we freeze it.”

Freeze — another new word — does not mean the production is encased in ice but means the day we stop making changes. That is right after the last preview, the day before opening night. So it’s chory, shapes, acting, then freeze. So, in short, no matter what is happening in front of me, the only performance that really matters is the one on opening night. After that our fate is sealed, after that the reviews come in (there is possibly a bad one sensitively placed right below or beside this very diary).

OCTOBER 10: We reach the moment in the film where Muriel tries on her first wedding dress. Kate and Keir Nuttall have written a beautiful song of transformation for this sequence which features (spoiler alert!) singing and dancing mannequin brides. This is a conceit I’d never get away with on film. Actually, these days, I wouldn’t even get away with the singing.

Our cynical (or is it jaded? Maybe just imaginatively challenged?) modern audiences giggle with embarrassment if an actor in a movie bursts into song. But on a stage, even in the least likely of situations (in Oliver! the kids sing in a workhouse) and at moments when singing would seem to be the least appropriate response (in Spring Awakening the characters sing while they have bad sex) the audience not only approves, they also applaud at the end of the song.

Personally, I think Bob Fosse killed the film musical in 1972. In Cabaret the characters weren’t permitted to sing anywhere but in a nightclub setting and all the non-naturalistic numbers from the original show were cut. After Cabaret the traditional non-naturalistic musical began to look a little silly. So it slinked backed to its original habitat, the stage, where it stayed for two film-free decades, usually written by Andrew Lloyd Webber or those French guys who did Les Mis (a few exceptions that prove the rule cropped up on the screen now and then, such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Grease and … what else? God, were there any successful film musicals at all in the 1980s?).

But, like the genetically doomed dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, musicals found a way to replicate, triumphantly returning disguised as animations such as The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast. Chicago in 2001 (Fosse again, but this time from the grave) worked, but even then it had to find an excuse for the characters to sing; as I remember all the numbers took place in Renee Zellweger’s fevered imagination.

La La Land went the full Jacques Demy (so Demy that it seemed like plagiarism to me) and dared to have the characters burst freely into song on street corners and in cafes. It was a hit, which seemed to indicate some audience acceptance of inappropriate public singing, but it didn’t lead to a spate of big screen musicals. Perhaps the answer is an all singing super hero movie? No: remembered how badly that went for Spider-Man on Broadway. Anyway, I should probably stop going on about film musicals and concentrate on this one.

What’s happening now? Oh, the mannequin brides are all falling over each other. “Brides! Don’t make it look like you’re running for the No 96!” Andy shouts. This gets a laugh from the Melbourne contingent of the cast; apparently that’s the number of the East Brunswick to St Kilda Beach tram.

OCTOBER 11: The Waterloo sequence — probably the most well known scene in the film. The original scene took a day to shoot but we’re on our third day of rehearsal. There’s a lot going on — an agglomeration of “shapes”. There’s Muriel and Rhonda, dressed as Frida and Anna from ABBA, performing on a stage on a stage, there’s the crowd going wild for the girls and, finally, there’s the vanquished Tania and her crew rolling around on the floor pummelling each other or “some girl-on-girl chory,” as Andy calls it. Some of the actors ask for kneepads. Andy, who I’m sure can grand jete without a warm-up, insists: “You won’t hurt your knees if you lift out of your hips and use your core.” This provokes much laughter from the cast, who have obviously heard this one before, and most of them opt for kneepads over cores.

I notice we’re getting a lot of visits from the Sydney Theatre Company staff who are thrilled that the company is finally putting on a musical, and an original Australian one at that. I’m not sure previous regimes considered musicals serious enough fare for the STC. Through the years I’ve seen Brecht, Genet, Beckett, and Cate Blanchett weeping and wailing in translations of Chekhov at the STC, but I can’t remember having ever seen a comedy, let alone something as frivolous as a musical.

We’re also one of the few STC productions not to take place on a minimalist set encased in a glass or plastic cube. We have actual sets and colourful backdrops, colour also being considered somewhat unbecoming to a civilised production. I just hope all the blues and pinks don’t scare the subscribers or, worse, kill one of them. (“He saw the backdrop for Porpoise Spit, doctor, and then … he died.”)

Fun seems to be equated with not serious or — more distastefully — with easy. (Oh, that it were so!) In fact, when the STC emerged as a possibility for our first run, a writer friend of mine scoffed: “The STC and musicals? If you can do an all singing and dancing Death of a Salesman they might consider it.”

OCTOBER 15: Scenes have been flying by lately, sketched out rather than fleshed out, and this is making me very anxious. I finally work out why: there are actors but no camera, there’s a lot of frenzied activity but no shooting.

On a film there’s very little rehearsal time before you shoot (sometimes actors aren’t available, but mainly it’s the expense — producers hate paying for something the audience will never see), so when a cast and crew are gathered together like this it usually means the camera is rolling (or recording since everything is digital now). And when you shoot the scene you have to get it right in that moment — or as close to right as you can — because it’s near impossible to go back and do it again. Whatever you shoot that day will be what the audience will see for the rest of the film’s life.

But here, despite all the people and energy in the room, we are not preparing a moment to be fixed forever on film, we are preparing a moment that will be seen much, much later on a stage. Even “fixing” is the wrong word: every moment in the show may well play differently on different nights. For a control freak like me that is a terrifying thought: that any show, no matter how well crafted, can suddenly have a bad night; that what plays brilliantly on Saturday might unexpectedly lose its mojo on Sunday. How can theatre directors stand it?

And the poor actors. Forget a line on an off night and you’re standing there dry, completely out of character, struggling to remember what on earth you say next in front of hundreds of people who paid lots of money to at least see you remember your next line. But in a film, if the actors are fresh, the script good, if that magic something happens, then the camera captures it all and that’s it; it will play the same way every viewing, across the years, forever and ever, Amen. Bill Hunter will always remember his lines, Toni Collete will always be radiant, hilarious and touching, and Rachel Griffiths will always be like lightning in a bottle. And that is why I love film.

OCTOBER 16: The cast does a stumble-through of act one. Stumble is the wrong word since it falls on its face within seconds and never really gets up, except sporadically (usually during Kate and Keir’s songs), but then, remembering that it is an invalid, it staggers, sways and falls on its face again. When it is done I sincerely regret believing Muriel’s Wedding could ever be a musical, almost as much as I regret my choice of writer: me. Every evening our stage manager Jessica Burns issues a rehearsal report. It is mostly a record of the day’s events — what scenes were worked on, who went to a costume fitting, prop requirements (“The credit card Betty gives Muriel needs to glow. Can it be covered in LED tape or something similar?”), additional set requirements. (“Sorry but it looks like we may need doors in the onstage side of the second portal legs, like the downstage” and, bizarrely, “What is the top speed the Harbour Bridge can fly?”) But it includes her brief assessment of the day’s work. To my surprise, Jessica writes of the stumble through: “She’s really coming together now!”

OCTOBER 17: I visit the costume workshop, which is filled with wedding dresses. There’s Muriel’s gown, an eye-popping explosion of tulle and satin, plus all the gowns she tries on during her serial-bride phase, as well as the gowns for the singing and dancing mannequin brides — which makes this production the indisputable champion of my career in staging fake weddings. Just how many have I staged over the years? It feels like dozens, but, actually, doing the maths, it has been only four: three for film and one for TV (not counting one I wrote for Jocelyn Moorhouse’s film, The Dressmaker).

There’s no difference between preparing a real wedding and a fake one. They both have to be catered, the florist has to be called, the church and the reception venue booked months in advance, and the bridal party must look great. Even the church service is the same except that the bride and groom don’t end up married after I call cut. I still remember Cameron Diaz on My Best Friend’s Wedding, her fingers crossed behind her back while on camera she delivered her vows with dewy-eyed sincerity. On Confessions of a Shopaholic, Krysten Ritter’s vows were unusable so clearly did she loathe the actor she was marrying.

OCTOBER 19: Sometimes I think Jessica doesn’t expect anybody to read her rehearsal reports. Today’s report reads: “Something pithy about getting there slowly but surely. I’m pithless. I’m taking the pith.”

OCTOBER 20: We do a full run-through of acts one and two. And though I am filled with dread after last week’s demoralising stumble-through, this run seems less plastered and more happily tipsy, suggesting that the inebriate may make it home alive. I have become suddenly aware of the fluidity in Simon’s staging, a seamless motion from one scene to another, which, perhaps unsurprisingly, reminds me of the movies.

But the real thrill is the growing confidence of our star, Maggie McKenna. Just like Toni Collete when we made the movie, Maggie is only 21. And, like Toni, she must be feeling the burden of carrying the whole show on her shoulders. One day, during filming, Toni confided to Bill Hunter that she was just waiting for everybody to discover that she was a fraud. Hunter replied, “Honey, if you’re lucky, they never find out.”

OCTOBER 21: We work on the funeral scene, a scene based on my mother’s funeral. I will never get over the sight of my dysfunctional family singing, my sad childhood dancing. I wish I could go back in time and tell my mother and my brothers and sisters: “Don’t worry, one day you will look back on this awful moment and it will be a little less awful because you will all be singing and dancing.” Why do musicals feel so — I don’t know — healing? It’s not because musicals are innately cheerful — some of Kate and Keir’s songs are downright heartbreaking — it’s something else, something beyond words. Maybe that’s it: music perfectly describes the things that can’t be described in words. Music bypasses the head, where the words live, and goes straight to the heart where the messy stuff resides. Jessica’s rehearsal report reads: “We’re polishing the rough edges and becoming shiny.”

Muriel’s Wedding opens tonight at the Sydney Theatre Company.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout