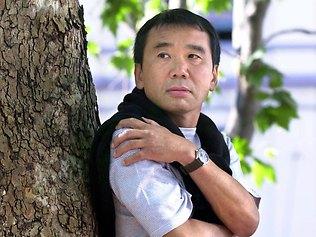

Murakami takes a long journey into strangeness

ONE of the mysteries of recent literary history - when half the planet is twittering - is the renaissance of the ultra-long novel.

ONE of the mysteries of recent literary history - when half the planet is twittering away in bursts of 140 characters or less - is the renaissance of the ultra-long novel.

From Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones (984 pages) to Roberto Bolano's 2666 (898), gigantism is everywhere in contemporary publishing. Even Jonathan Franzen's 575-page suburban epic Freedom seems undernourished when placed beside his younger compatriot Adam Levin's 900-page behemoth, The Instructions.

Theories abound. Some point to the enduring cultural cachet of David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest, a thousand-plus page gauntlet thrown down to the bite-sized inanity of pre-Sopranos-era TV. Others point to the overwhelmingly male writers who make up this literary subset: the "mine is bigger than yours" school of literary brilliance. Canny folk may point to the way the internet's endless proliferation is reflected in emerging narrative forms. Cynics will note the number of editors made redundant in recent years.

Then there is the example of IQ84, Haruki Murakami's 12th novel and, at 925 pages, his most ambitious in form and scale. Of course, for the Japanese author, an obsessive long-distance runner, endurance has its own rewards; having finally emerged from the single volume that contains the three, separately published books from which the original Japanese novel was assembled, readers will feel the same shaky mixture of euphoria and exhaustion of someone completing a marathon, pushed well beyond their usual mental zones of comfort and ease.

But there is more here than the satisfaction of an arduous task completed: IQ84 's capaciousness has a moral dimension. Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin said of Dostoevsky that he invented the "polyphonic" novel. Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz agreed: "Polyphony makes Dostoevsky a modern writer: he hears voices, many voices, in the air, quarrelling with each other, proclaiming contradictory ideas -- are we not all in the present phase of civilisation exposed to this raucous chaos?"

Murakami, who was born in Kyoto in 1949, during the post-war American occupation of his nation, is a writer exposed to a tumult noisier and more complex than his Anglosphere colleagues. The differences between Murakami's homogenous and isolate local circumstances, and the dazzling promiscuity of global culture in the second half of the 20th century, have been profound.

Like Dostoevsky (a touchstone writer whose The Brothers Karamazov Murakami seeks to emulate within IQ84), the Japanese writer's work embodies the fissiparous relations of an inwardly turned empire and Western modernity. Murakami's new novel is long and strange on purpose: long, because it wants to cram as many contesting voices into its pages as his 19th-century idol did in his; and strange, because when scientific determinism meets humanism, Kanji characters are translated into Latin alphabets, Western counterculture clashes with Japanese conformity, and technological rationalism and folk superstition inform social life, the subsequent blending leads to bizarre literary mutations: magical realism, only gene-spliced, turbo-charged, hypertexted. In other words, these days, mere polyphony doesn't cut it.

Only the symphonic does justice to the sound of global culture as it floods over Murakami's island nation. So it is unsurprising that IQ84 should begin in the year 1984 with the sound of Czech composer Leos Janacek's Sinfonietta bursting from the speakers of a Tokyo cab, stuck in the middle of a traffic snarl on an elevated freeway: a noise at once alien and discordant, yet eerily familiar to the passenger who immediately recalls the work's title, even though she knows little about classical music.

Aomame (the literal translation is "green bean") is an attractive young woman running late for an appointment. On the cabbie's advice she abandons the vehicle and makes her way to an emergency stairway, leading to the street level below. Somewhere in her progress, however, Aomame leaves her everyday reality and steps into a similar yet altered world. The moon, for example, is suddenly shadowed by paler, smaller twin; news reports of a religious cult and its violent engagements with the police, absent from Aomame's original reality, take on a significance that she intuits without fully understanding.

These shifts are so slight, and come upon Aomame so gradually, that she simply incorporates them into daily life. She continues to work her day job as a fitness instructor and masseuse, while freelancing on the side for a shadowy organisation, backed by a rich and politically connected old lady, that contracts her to kill, via discreet and highly professional means, men who have beaten, raped and otherwise humiliated women.

As her career mix indicates, Aomame is a marvellously complex character. The child of religious fundamentalists who abandoned her faith in childhood and was subsequently ostracised by her family, she combines absolute discipline of body and mind with strong if eccentric sexual drives (Aomame is only attracted to men with thinning hair) and a hopelessly romantic idea of love. A boy from school with whom her closest contact was a tightly squeezed hand years before remains her beau ideal. But she has not seen him since that time and refuses to go in search of him. They will meet by chance, or not at all.

In fact, this boy, named Tengo, now a unpublished author and mathematics lecturer at a Tokyo cram college, is the subject of the novel's alternate strand. An elegant and even gifted writer, although one lacking in great passion, Tengo leads a quiet, orderly existence until his friendly editor Komatsu (a mysterious, Machiavellian figure in Japanese literary circles) asks him to rewrite an inspired if naively constructed novella originally by a beautiful 17-year-old schoolgirl, in the hopes that a more polished version might win a leading literary prize.

It does win, and on publication Air Chrysalis becomes a bestseller, with its young author, her pen-name Fuka-Eri, becoming a celebrity. Few, including Tengo, know that she did not imagine the novella's contents but directly related the bizarre reality of her upbringing as the daughter of a cult leader, and her knowledge of creatures known as the "little people", miniature figures who emerge from the mouth of a dead goat and weave chrysalises from diaphanous white stuff.

The arrival of the little people in IQ84 marks the beginning of the novel's long journey into strangeness. Yet their appearance also begins the braiding together of the work's narrative strands. When, at the same moment that Fuka-Eri disappears - leaving a message for Tengo that warns of the little people's potential displeasure at the disclosure of their secrets - Aomame is approached by her employer and given the task of killing a cult member who assaulted a young girl in his care, the two worlds of IQ84 begin to merge.

It would be unfair to linger over the fantastical elements that come increasingly to the fore by the novel's middle section: they are augmentations and not distractions from the larger tale. For all the novel's length (and, yes, it could do with an edit) the narrative is not dull, just delayed. As with all Murakami's fiction, human simplicity operates as an anchor against oddity: the endlessly attenuated story of boy meets girl, boy loses girl and so on, is never wholly lost from sight, despite the phantasmagoric backdrop against which Aomame and Tengo move.

It is in the light of this inviolate idealism that we should read the title of 1Q84, with its play on George Orwell's dystopian classic. Though there are scattered hints throughout the text linking the two titles, they feel like false alleys.

Who could read these two men, however, and fail to note their essential faith in humanity, their mutual hatred of systems that seek to enslave or destroy us. They both (in Janacek's words, in explanation of his Sinfonietta) celebrate "contemporary free man, his spiritual beauty and joy, his strength, courage and determination to fight for victory".

IQ84

By Haruki Murakami

Harvill/Secker, 925pp, $39.95 (HB)

Geordie Williamson is The Australian's chief literary critic and winner of the 2011 Pascall Prize for criticism.