Mrs Kelly’s Astonishing Life: Ned’s mother and her outlaw family

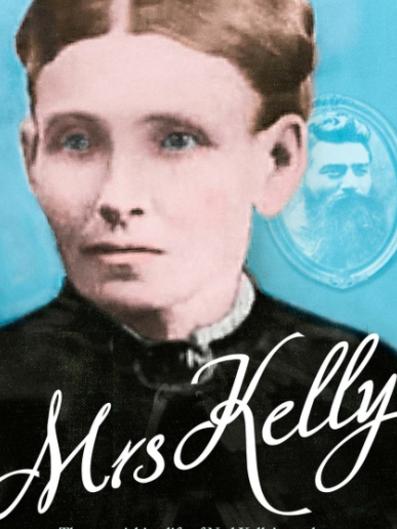

A biography of Ned Kelly’s mother offers new perspectives on the legend of the outlaw family.

Near the end of his rollicking account of Australia’s most notorious outlaw family, Grantlee Kieza zooms in on Ned Kelly’s last words:

The reporters are all too far away to hear with any certainty what Ned says. One thinks it is “Ah well, I suppose it has come to this”, while another thinks that he has stopped in mid-sentence and simply said, ‘‘Ah well, I suppose …” As the seven stunned journalists … quiz each other in whispers about what Ned might have said with his last desperate breath, [Melbourne Herald reporter Jim] Middleton tells himself he has a great quote. He jots down three words: “Such is life”.

How Kieza could be privy to what Middleton ‘‘tells himself’’ at such a moment is a question some readers might be tempted to ask, but most will probably be carried along by the drama of the scene. In any case Kieza is scrupulous here, and throughout the book, to provide references to enable us to check the record for ourselves. (As Ian Jones and others have pointed out, the words ‘‘Such is life’’, if spoken at all, were probably said the day before, when Ned was told the hour of his execution.)

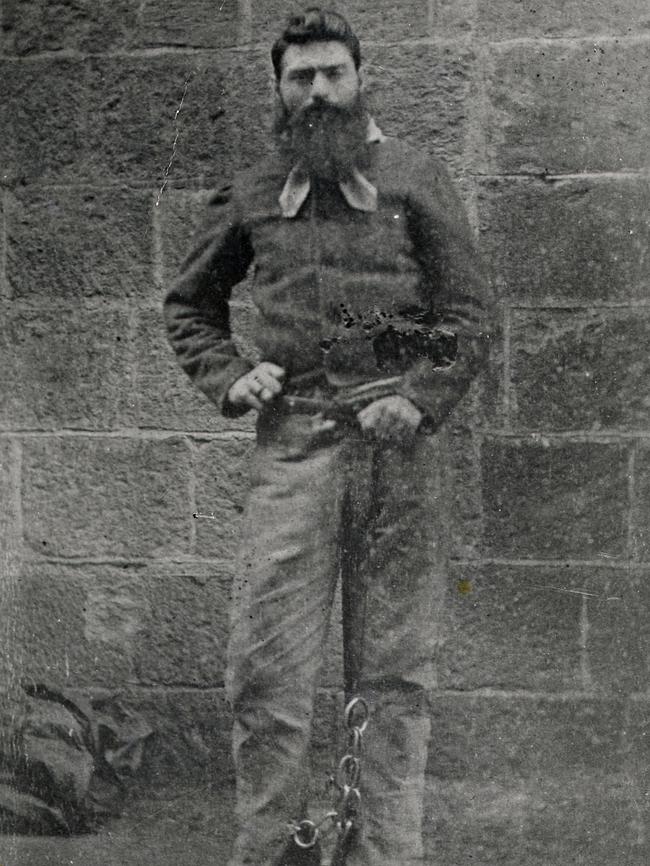

If historians cannot agree on Kelly’s final words, it is scarcely surprising that his life itself remains contested. Is Ned ‘‘one of Australia’s greatest folk heroes’’, as he is described on the federal government’s About Australia website; is he the ‘‘social bandit’’ portrayed by John McQuilton and others, an idealistic martyr-hero fighting for the rights of downtrodden selectors? Or is he, as conservative commentator Gerard Henderson argues, nothing more than a ‘‘cop killer’’, the leader of a gang of ‘‘violence-prone, narcissistic thugs’’?

In Mrs Kelly: The Astonishing Life of Ned Kelly’s Mother, Kieza weighs these competing versions of the Kelly legend. The title is a little misleading, since for most of the book Ellen Kelly is in jail, a long way from the action. But even offstage, Ellen remains a central figure in the story of her son’s rampage. In the Jerilderie letter, Ned railed at his mother’s persecution by the ‘‘big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police’’.

Where Kieza stands apart from previous authors is in his efforts to present Ellen Kelly as a fully realised character, a tenacious and spirited woman whose experience of life helped shape the course of Ned’s outlaw career.

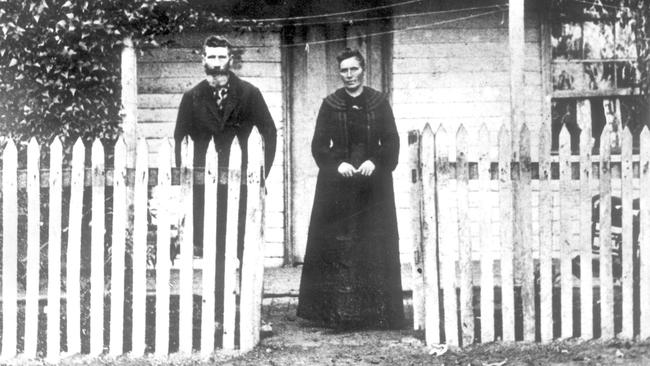

Born Ellen Quinn in 1832 ‘‘on the northern tip of an emerald-green land stained with blood’’, the future Mrs Kelly left Ireland with her parents and seven siblings, arriving in Port Phillip in July 1841. Nine years later Ellen married John ‘‘Red’’ Kelly, a Tipperary pig thief transported for seven years. Her first son, Ned, was born in December 1854, the same month as the Eureka uprising.

After Red Kelly drank himself to death, leaving Ellen with seven young children, 11-year-old Ned signed the death certificate. By then, Kieza tells us, Ned had already made his first appearance in court, he and his mother having sworn an improbable alibi for an uncle charged with cattle-stealing. The court did not believe the alibi and sentenced Ned’s uncle to three years’ hard labour.

‘‘Ellen has either told the truth or coached Ned to lie under oath,’’ Kieza writes. ‘‘The law was either an ass or a shrewd and dangerous enemy, and Ellen’s relatives are becoming known as a ‘criminal brood’, a bunch of thugs and thieves.’’

Whether Kieza believes Ned told the truth or not (the latter seems more likely), the idea of Ellen as a mother who schooled her then eight-year-old son to perjure himself in court is bound to colour our reading of their relationship and of Ned’s future exploits.

If Red Kelly proved to be an unfortunate partner for Ellen, others were worse. Bill Frost got her pregnant but scarpered after the child was born, eventually being forced by the court to pay five shillings a week for two years towards the child’s upkeep (one of Ellen’s few triumphs in a courtroom, Kieza points out).

A year later, Ellen began a relationship with George King, a Californian horse-thief 11 years her junior. By then Ned was in jail for the ‘‘violent assault’’ of Jeremiah McCormick. In a defence worthy of the rugby league judiciary, Ned claimed that ‘‘my fist came in collision with McCormack’s [sic] nose and caused him to lose his equilibrium and fall prostrate’’. King married Ellen but deserted her four years later, having fathered three children. Maybe Ned, sick of King’s violence towards his mother, sent him packing with his fists. Maybe that wasn’t enough. Kieza recounts the rumour that Ned ‘‘took George for a ride into the secret caverns of the nearby ranges and only Ned came back’’.

At the age of 46, Ellen gave birth to her 12th baby, Alice. Just two days later, on April 17, 1878, Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick came to the house looking for Ned’s brother Dan, who was wanted for horse stealing.

Arguments over what happened that afternoon have raged from the moment Fitzpatrick stumbled into the Benalla police station, smelling of brandy but ‘‘certainly not drunk’’, claiming to have been shot in the wrist by Ned Kelly. Ellen, he says, walloped him with a spade. Keiza writes:

Ellen will do anything to protect her children, even if they’ve been up to no good. She’ll scratch and claw and scream. She’d likely even kill for them. She wheels on Fitzpatrick with an anger that would startle even her mad brother Jimmy Quinn. ‘‘Ye deceitful little bugger,’’ she snarls at the policeman, “I always thought ye was a sneak”.

An endnote attached to Mrs Kelly’s outburst attributes her words to an anonymous article in the Perth Mirror headlined “A Kelly Gang Echo” and published in January 1923. Kieza’s detailed referencing makes it easy to find the original article online. The newspaper article does not quote the words spoken by Ellen Kelly, reporting merely that ‘‘Mrs Kelly was highly indignant at the trend of events and abused the constable, whom she described as a sneak’’. As with the hanging scene, Kieza has taken some licence with his sources. I didn’t mind but some might.

Many, including police commissioner Standish, excoriated Constable Fitzpatrick, but Kieza is on his side, noting that while the Kellys’ version of events changed with every telling, Fitzpatrick’s ‘‘will hardly deviate in the 33 years between 15 April 1878 and when he is interviewed for newspapers in 1911’’.

The consequences of the Fitzpatrick incident were calamitous for the Kelly family. Sentenced to three years’ hard labour for ‘‘wounding with intent to prevent lawful apprehension’’, Ellen told a fellow inmate at Beechworth Gaol that ‘‘there would be murder now’’. Ellen never saw Dan again. She was reunited with Ned in Melbourne Gaol only to see him hanged for the murder of constable Thomas Lonigan at Stringybark Creek.

Kieza gives short shrift to Kelly apologists who argue that the three policemen, Lonigan, Scanlan and Kennedy, were shot by the outlaws in self-defence. Referring to the claim made by Ian Jones in Ned Kelly: A Short Life (1995) that the police carried two long leather straps to remove the bodies, Kieza points out that ‘‘no one ever mentions body straps at the time, nor does Ned Kelly ever bring it up as evidence’’. This is a significant fact if the police party really was an ‘‘execution squad’’ with orders to kill the outlaws rather than arrest them.

The Stringybark Creek murders ensured there could only be one outcome for Ned, his brother Dan, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, although only Ned met his end on the gallows.

Kelly sympathisers will find plenty here to infuriate them, but it would be a mistake to lump Kieza’s prodigiously well-researched and generally even-handed book with polemical studies such as Ian MacFarlane’s The Kelly Gang Unmasked (2013) and Doug Morrissey’s more vituperative Ned Kelly: A Lawless Life (2015). Kieza’s purpose is less to tear down the myth of Kelly as hero than to let it collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

Ellen Kelly may not get as many pages as Ned but she is never far from our minds, knuckling down to her three-year stretch in hopes of winning early release by her good conduct. A 46-year-old grandmother when she was sent down by Judge Barry, Mrs Kelly spent her first year in Beechworth Gaol nursing her baby Alice. Her determination not to cause trouble stood in stark contrast to Ned’s headlong gallop to ruin.

Constable Thomas McIntyre, the only policeman to ride out of Stringybark Creek alive, saw Ellen as a sympathetic figure. ‘‘It was thought by some that the punishment allotted to Mrs Kelly for her attack upon Fitzpatrick should have been months instead of years of imprisonment,’’ he wrote in his unpublished 1902 manuscript, A True Narrative of the Kelly Gang. ‘‘She had one of the most tragical and harrowing experiences that human nature can furnish, for she was confined in the jail in which her unhappy son suffered the last punishment of the law.’’

Kieza does not attempt to exonerate individual police of brutality, incompetence, cowardice, bigotry and stupidity. He leaves the reader in little doubt that the bashings Ned Kelly suffered from Lonigan and constable Edward Hall (who left the 16-year-old Ned needing nine stitches in his head) instilled in him a visceral hatred of all police.

Ned, however, was no Robin Hood. Before they took to robbing banks, Ned and his gang stole horses on an epic scale, often from struggling farmers no better off than his own relatives. Much of the money went on buying the loyalty of the gang’s army of spies and supporters. Ned dressed ‘‘flash’’ while his long-suffering mother lived ‘‘in abject poverty’’.

Mercurial, vain and impetuous, Kieza’s Ned Kelly is a charming liar with a hair-trigger temper whose ‘‘predilection for violence’’ brought disaster on everyone around him. Few disputed his physical courage, yet Ned could shoot a defenceless man in cold blood and loot his corpse.

Tom Gilling is an author and critic.

Mrs Kelly: The Astonishing Life of Ned Kelly’s Mother

By Grantlee Kieza

ABC Books, 616pp, $39.99 (HB)