Mouth full of music

A Brisbane beatboxer and an orchestral conductor teamed up to create a world-first show that’s since gone global.

Waiting in the wings moments before their concert debut, Tom Thum and Gordon Hamilton are quietly confident that they’re on to something special. It is a Saturday night in May 2015 at the Brisbane Powerhouse, and they’re about to unleash a sonic pairing that has never been heard before. Seated in the crowd are several hundred people from two worlds that rarely cross paths — and might never again if the whole show fails miserably.

Hamilton is a composer and conductor who has worked with orchestras and choirs for much of his career, including vocal ensembles such as The Australian Voices. He’s the one holding the baton that will soon direct 16 members of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra to perform an hour of original music. While that’s pretty standard stuff for the classical realm, his offsider’s artistic role in proceedings is a little more unorthodox, to put it mildly.

Thum is a musician who carries his instrument wherever he goes, for it is inside him. As a teenager, he became a boy who swallowed an orchestra. What began as an adolescent investment in learning the skill of beatboxing has since bloomed into the lyrebird-like ability to mimic just about any sound using only his voice.

Beatboxing is the percussive vocal style most commonly applied to the hip-hop genre, where it provides a backing track to rappers trading rhymes on the street. It’s more at home in that environment than at seated halls such as the Powerhouse theatre, which is why the pair are sweating ever so slightly about the potential reception for this first performance of a show named Thum Prints.

Despite their confidence in the work and the musical talent of all involved, they truly have no idea as to how the respective audiences from the classical and urban genres will respond to this cultural clash. As the lights go down, they walk out into the theatre together — both wearing dark suit jackets but with Thum’s outfit offset by a tropical shirt and bright sneakers.

Will the conductor and the lyrebird end the night with adulation befitting their shared roles as musical innovators? Or will they rue the day they ever decided to combine forces with the lunatic idea of arranging an hour of original music whose roots were planted deep in the fertile creative mind of a boy making strange, repetitive noises in his bedroom?

■ ■ ■

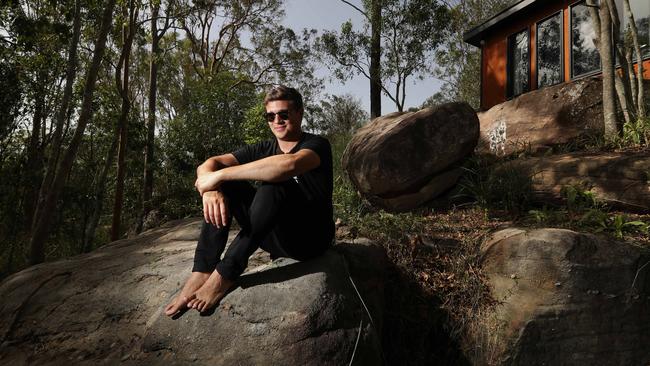

Thum calls this building “the hide”, and as he parts the thick black curtains to reveal the beautiful native bush view on the other side of the window, it’s easy to see why. On the pathway outside, a family of friendly magpies gently caws for his attention, while all sorts of birdlife can be seen from inside this structure that overlooks a small valley. For a man devoted to generating an unnatural battery of noise, this is a decidedly natural locale for music-making.

Built with his father in the backyard of a 6500sq m property near Ipswich, 44km southwest of Brisbane, the airconditioned and soundproofed studio features a hefty desk cut from a slab of red gum, while the speaker stands are made from the timber of an old shed. In the corners of the black and brown-themed room are tree designs jigsawed by the artist himself, while on his desk is not much more than a laptop, a computer monitor, an Akai keyboard and a microphone stand.

While there are no other musical instruments in sight, as soon as Thum enters a room, it is suddenly filled with the potential for any sound his singular mind can conjure. Born Tom Horn and raised in Brisbane’s inner south, the self-described “hyperactive kid with too much time on his hands” grew up exploring each of the four elements that hip-hop culture is traditionally composed of: aural, physical, visual and oral. His interests in rapping, breakdancing, graffiti writing and sound manipulation eventually led to a focus on beatboxing, which some purists consider the fifth pillar of the art form.

Thum’s abilities soon became known and respected among Australia’s underground hip-hop community. In 2005 he won first place in the team battle at the World Beatbox Championships, held in Leipzig, Germany; in 2010 he was awarded best noise and sound effects at the World Beatbox Convention in Berlin. Since 2007 he has toured the world as a performing artist in a variety of guises, including five years with Tom Tom Crew, a theatre troupe that featured five acrobats backed by three musicians who blasted loud drum’n’bass, dub and hip-hop.

He has also released three albums as a rapper under the name Tommy Illfigga, as well as a handful of shorter works composed, produced and recorded as Tom Thum. His voice has appeared on platinum-selling singles by artists such as Adelaide trio Hilltop Hoods — the 2016 song 1955, which also featured Sydney singer-songwriter Montaigne — and his commitment to the craft has seen him catch an updraft that has sent him soaring higher than any of his peers have ever gone.

Frequent injuries forced him to quit breakdancing in 2013, the same year that he began to attract global attention following a performance at the Sydney Opera House as part of the TEDx Sydney conference. “My name is Tom, and I’ve come here to come clean about what I do for money,” he said upon taking the stage. “I use my mouth in strange ways in exchange for cash.”

Across 11 minutes, he gave a virtuosic demonstration of his ability to construct intricate compositions on the fly by stacking a vast array of sounds, tones and colours with the assistance of a looping station. As his act unfolded, ripples of recognition spread across the concert hall of about 2200 people: the young man working the microphone was a musical genius. When met with a standing ovation, Thum grinned, jumped and clicked his heels together.

That breakout Opera House performance has since attracted a combined total of 83 million views on YouTube. While the online exposure led to commercial jobs for the likes of global companies such as Audi and Disney, one of the strangest outcomes came from an ensemble located not far from his parents’ backyard in Annerley, the Brisbane suburb where he lived at the time.

Dale Truscott was among the millions of viewers won over by Thum’s abundant talents, and as a musician and project manager at the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, he saw an opportunity to bridge two worlds. “We loved the idea of unpacking the diverse sounds in his arsenal and pairing him with a creative young composer who could ‘translate’ them into an orchestral work, to break down all of the boundaries between hip-hop culture and the concert hall,” Truscott tells Review. “Tom and Gordon got on like a house on fire from the day we first introduced them.”

In response to that offer, Thum immediately said yes. “It was something that I wouldn’t ever have thought of doing,” he tells Review at his home studio. “I had no idea at the time about the intricacies of working with orchestras, which was a very steep learning curve; it was like the half-pipe of learning curves”.

On a Skype call from Berlin, where he is working on The Magic Flute with the Berlin State Opera as assistant conductor, Hamilton tells his side of the story. “I was really impressed with how very musical Tom is,” he says. “He’s not a trained musician in a classical sense, but he is aware of all the things that are important: rhythm, tone, colour, dynamics, structure and memorising. His whole array of sounds still surprises me; it’s so strange to hear his electronic-sounding noises coming out of a human face.”

Importantly, the pair agreed from the outset that they were to be equal collaborators in the task of composition. Hamilton — who, at 36, is two years older than Thum — describes this concept as that of “two sound forces meeting; neither should be subordinate to the other”. “We also want to avoid cliche as much as possible; we don’t want it just to be some nice Mozart, Bach or Tchaikovsky. We want both musical elements — orchestra and beatboxer — to flourish, to be itself, and to be fully engaged, doing creative and interesting things”.

Some of Hamilton’s favourite moments during this fruitful creative partnership are when his offsider opens his mouth for the first time among strangers. “It’s great to watch the musicians’ reactions, every time we start rehearsing with an orchestra,” he says, smiling. “I can imagine that some people might anticipate the project with some scepticism, and I love watching Tom convince them with his extraordinary ability. You see them recognise him as a real musician, even though he plays an instrument that’s very strange.”

Is it fair to say he’s a bit of a misfit in the classical world? “Yes, but musicians everywhere recognise when someone is talented,” the conductor replies. “They recognise that Tom has this special gift, and they go along. It’s undeniable: you can’t spend five minutes with Tom and not be convinced of his musicality.”

To their knowledge, the concept of merging these two disciplines with original music had never been explored before; past ventures extended only as far as a beatboxer “drumming” alongside an orchestra. “We wanted to totally flip that on its head,” says Thum.

That they did, is demonstrated in Ratchet Face, the three-minute set closer that begins as a solo work with Thum’s looped beats and vocals filling the space. One minute in, though, the full force of the orchestra erupts into the driving melodic motif established by his voice. The effect is intoxicating, moving and hair-raising, all at once.

As he rewatches YouTube footage of that song at Review’s suggestion, Thum can’t wipe the grin from his face. This is a track that he developed in his bedroom at his parents’ house, with the door shut and headphones on. To go from that private, intimate moment of creation to feeling and hearing the weight of so many musicians is enough to give him goosebumps all over again as he remembers the energy of the orchestra at his back.

The power of that Ratchet Face clip is indicative of the entire concert; all involved with it consider it a resounding success. “The crowd reaction at the end of Tom’s first show with the orchestra was unreal,” says Truscott, who left the QSO last year.

“None of the regulars were used to the roar of approval from Tom’s fans for what Tom, Gordon and the orchestra had created. We’d unleashed a monster!”

■ ■ ■

Sitting at his red gum desk with Hamilton on the line from Berlin, the beatboxer counts off the far-flung locales that Thum Prints has been heard in. That first show with a 16-piece version of the QSO was soon followed by full orchestra shows at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre and Cairns, and with the Sydney and Perth symphony orchestras.

Beyond our shores, it has been performed in Manila, Nuremberg, Cologne and Lithuania. This month they performed two concerts in Kuala Lumpur with the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra; at the end of this month they’ll return to Nuremberg, followed by another German gig in September at the Beethoven Festival in Bonn, then on to Florida in November.

It has proved to be a remarkably transportable work that they offer as a 20-minute “concerto” or as an hour-long concert. Amid their other musical and touring commitments, it has become something of a regular highlight for both of them, although the need to cram rehearsals into just a couple of days with each new ensemble is something they both find exhausting and challenging, but highly rewarding.

“I try to be really serious with my music, and I try to only have ideas that are good, worth showing and worth repeating,” says Hamilton. “I think that what we’ve done together is a really cool and worthwhile artistic statement. I stand by it. As a composer, I enjoy smooshing things together that don’t normally belong.”

The success of Thum Prints also became the impetus for the QSO to collaborate with a suite of other artists who rarely rub shoulders with the classical world. The orchestra has worked with Sydney hip-hop duo Horrorshow and electronic artists such as the Kite String Tangle, Sampology and Tim Shiel. In each of these partnerships, Hamilton has played a key role as arranger and conductor; in May, the QSO will perform a Brisbane show with Blue Mountains hip-hop group Thundamentals.

After farewelling his friend in Berlin, Thum says that in quieter moments he reflects on the vulnerability of his music, contained as it is within the fleshy confines of his throat. “It’s not something I can replace or borrow from someone,” he says. “Even sitting in an airconditioned rehearsal room can totally screw my voice. I do think of that a lot — that when I lose my voice, I lose all the instruments.”

Although the boy who swallowed an orchestra is unsure about exactly where his musical career is headed, it has been ever thus. He didn’t see the orchestral project coming, and now it’s a big part of his life. In a sense he’s carving a path as dense as the sunbaked bush seen outside his studio window.

No other musician possesses his combination of talents, nor has taken them so far, from suburban Brisbane to the rest of the world.

Tom Thum performs as part of As Yet Unheard at Adelaide Fringe’s Garden of Unearthly Delights tonight and tomorrow (Sunday).