Mine field: Radical Newcastle a disservice to history by academics

Radical Newcastle might be the best evidence yet for what is wrong with how we approach history in Australia.

The seaside industrial city of Newcastle harbours a rich history of achievement born of rebellion. It was here that convict James Hardy Vaux began penning a lexicon of criminal language thought to be the first Australian dictionary produced, and where Joseph Lycett took a break from forging banknotes to design church windows before cutting his own throat to escape authorities.

It’s no wonder the historians at the University of Newcastle, who produced this collection of essays, were so keen to chronicle the city’s great unsung, and the title of their book certainly promises something special from the city whose rabid surf culture of the 1960s and 70s helped to rehabilitate the word “radical” as an acknowledgment of something outstanding.

But the problems with Radical Newcastle begin with the authors’ preferred definition of the word. The introduction points us to The Oxford English Dictionary: “advocating thorough or far-reaching political or social reform; revolutionary, especially left wing”.

The emphasis is mine, but the decision is theirs: nearly every chapter deals with matters of a communist or socialist bent, or with stories shoehorned into such a definition. (Newcastle Herald journalist Joanne McCarthy decides her chapter on child sexual abuse in the clergy deserves inclusion because it was “a radical step” for her paper to report on it, as if newspapers have traditionally drawn the line at exposing scandals.)

The authors have the right to set their own parameters, but it does raise the question as to why. For what reason did the history department of Newcastle University believe the story of the city, so tragically untold, could be resurrected by a book almost exclusively about socialism? It’s not as if Newcastle pinkos have had it so bad; the nation’s only dedicatedly Labor division since Federation, Newcastle is practically a socialist’s holiday resort, where to be politically conservative is to be radical in any common sense of the word.

As if this politically motivated culling of good history isn’t mean enough, the introduction warns us not to expect anything as spectacular as the lives of Vaux and Lycett, or the tale of post-earthquake corruption in 1989, or the Depression-era eviction riots, for to “focus on high-profile incidents may leave out the tireless activists who organised and campaigned without achieving public notice”.

In other words, the more noteworthy the story, the less likely it is to appear. Thus frontier scientists such as Henry Leighton Jones, arguably Australia’s first endocrinologist, who transplanted monkey testicles into human beings in his bushland laboratory in the 1930s, and mavericks such as Ben Lexcen, the abandoned and uneducated child who went on to win the America’s Cup with his radical marine architecture, are ignored specifically, it seems, because their stories are worth writing about.

What we get instead are the sapless lives of low-level political obsessives, the reader dunked into in a bath of acronyms as the lacklustre protagonists shuffle from one meeting to the next of the CPA, the TLC, the CMUC, the WIUA, ad nauseam. Two priests score a chapter each for the fact their socialist views “discomfited” their parishioners. We are invited to give a toss about the spectacularly dismal saga of the proposed closure of the Mayfield public swimming pool, written by a committee of no less than four authors, which predictably reads like a report commissioned by council.

One essay authored by two people lapses in and out of first person, and every second chapter reads like a school assignment, to wit: “This is a story of Newcastle Medical School through the critical gaze of radicalism. The aim is to explore … [then, seven dreary pages later] … This account of the first decade of Newcastle Medical School shows how radicalism flourished … ”

It’s as if someone grabbed a handful of term essays from a lecturer’s desk and published them sight unseen.

Lisa Milner’s chapter on “Newcastle’s Post-war Cultural Activists” promises some relief from the drudgery, but we get nothing about rock ’n’ roll, or art, or punk, all of which were strong countercultural forces in Newcastle. Instead, we learn that “the centre of cultural activity in Newcastle” was — you guessed it — the Trades Hall Council Workers Club, and we are frogmarched through the activities of the Communist Party-funded New Theatre.

About 20 plays are laboriously name-checked (“Out of Commission by Mona Brand, Childermass by Tom Keneally and The Legend of King O’Malley by Michael Boddy and Bob Ellis were other scripts selected”), but we learn nothing about the actual performances, the only witness account coming from a gushing ‘‘review’’ in the Newcastle Trades Hall Workers Club Journal.

This isn’t history. It’s more like record keeping, a catalogue of dates, people and places bound together with the romance of a street directory. It is no book for a reader, or a history junkie, or a lover of Newcastle, or even the most passionate socialist.

One of the better chapters, Shane Hopkinson and Tom Griffiths’s essay about activist Neville Cunningham, betrays a story laced with tragedy: the man who sacrificed his marriage and whole working life to communism concludes, at the end of his life, that his cause has been a lie. But the heartbreak is lost in a barely eulogistic biography, authored by men who appear to have known Cunningham personally.

It’s symbolic of this book’s bloodless approach to history that we never seem to learn of how characters we are meant to care about ended their lives: publisher JJ Moloney “died suddenly in Sydney”, academic David Maddison faced a “tragically premature death in 1981”. Readers are left to guess whether their ends came through heart attack, suicide or meteor strike.

The biggest disappointment of all is Bernadette Smith’s chapter on the Star Hotel riot of 1979, described in the introduction as “a compellingly captured … eyewitness account”. It is nothing of the sort, the author admitting in her essay that she missed the riot completely, showing up only to photograph the “last remnants of the crowd of onlookers and the scattered wreckage” of a violence that had long since punched itself out.

It would have taken little more than a shout-out on social media to find some genuine witnesses and participants who could have told this remarkable story blow by blow. Instead, Smith contents herself with writing a scholarly treatise on the brawl, as seen through the rear-view mirror of an earnest academic breaking the speed limit on her way to a PhD. A big fight in a pub, initiated when the cops turned off the beer, becomes “a struggle for the acceptance of pluralism”. Give me a break.

There’s a reason why Ned Kelly is Australia’s most popular historical figure, and it’s not because he attended committee meetings. A breath of fresh air among the gallery of public servants who jostle for space in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Ned was a lone wolf, waging an entirely freelance rebellion against personal poverty and the hypnotic tedium of life under authority, political or otherwise, which is something every Australian can understand.

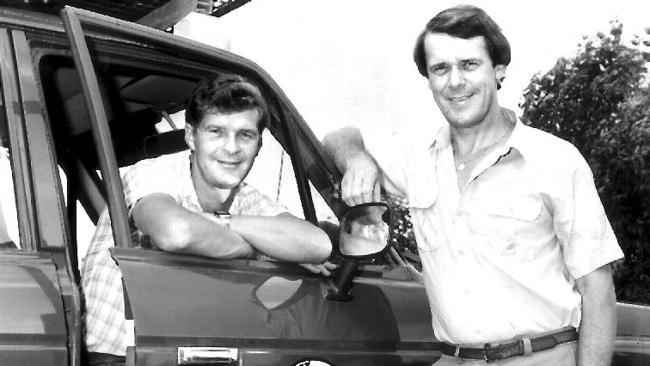

So, too, were the residents of Clara Street, Newcastle, who physically charged police in defence of their homes during the eviction riot of 1932, and “serial pest” Peter Hore, whose reckless moments of cultural terrorism have made him world-famous. Mark Richards dropped out of high school — with his parents’ blessing — to surf his way to a world title in 1979, when surfing was such a marginal sport that a wristwatch was his only prize, and the Leyland brothers took on Get Smart and The Brady Bunch with little more than a Kombi, urging Australians to love their natural inheritance at a time when mindless journeys were anathema to television.

None of these Novocastrians gets a guernsey in Radical Newcastle — not even Joy Cummings, who waded headlong into a political gender tsunami to become Australia’s first female lord mayor in 1974 — and that’s bewildering. The authors doubtless feel that in producing a book about politicised nobodies written in the most spartan academic style, they offer us something worthy that transcends the cheap appetites of sensationalist culture.

They’re wrong. What we have here is trash, frankly, which will live next to clip jobs of Kim Kardashian in bargain bins across the country. That’s a tragedy for the unpublished history of Newcastle, for it’ll be a brave publisher who’ll be prepared to touch the subject when the sales of this tome are docketed.

If you think I’m being unfair, think about what this book represents. Radical Newcastle is the work of almost the entire history department of one of our leading universities, edited by the head of that department, a senior lecturer thereof and an “award-winning” alumnus, with graduates making up more than three quarters of the list of contributors. These are people who educate our history students. They set the benchmark when it comes to the study and proliferation of the story of Australia, and are approached by politicians to carve out the syllabus for generations of suffering children, who stagger home from school anxiously wondering what’s wrong with them that they can’t get interested in the gold rush or Federation.

Radical Newcastle may be the best evidence yet for what is wrong with how history is approached in Australia, not to mention education in a higher learning facility. That these well-paid intellectuals have put their heads together and produced a history book so deliberately drab and politically exclusive should be cause for a royal commission, not just a lousy review in a national newspaper.

Jack Marx is a Newcastle-born journalist and author.

Radical Newcastle

Edited by James Bennett, Nancy Cushing and Erik Ekland

NewSouth, 333pp, $39.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout