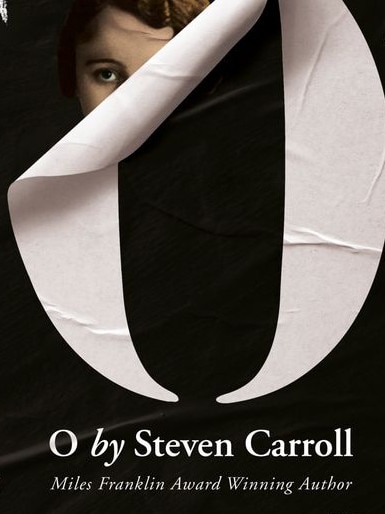

Miles Franklin winner Steven Carroll’s retelling of The Story of O

The most notorious erotic novel of the 20th century is no longer merely the effort of a woman in love to titillate her lover.

Paris, 1950s. A beautiful fashion photographer is taken by her lover to a secluded chateau on the city’s fringe. There, marked as a slave, she is stripped of clothing and dignity, blindfolded and imprisoned.

Over the days and weeks that follow, the woman, known only as O, is subjected to acts of violation and degradation by members of a secret society with the connivance and encouragement of her lover. We learn that these men are preparing O for even more exacting sadomasochistic encounters.

What shocks most about this brief, partial precis of The Story of O — the most notorious erotic novel of the 20th century, first published in France in 1954 and now point of origin for a new work by Miles Franklin-winner Steven Carroll — is that O undergoes all this willingly. She does it for the love of the man who gave her up to others as sexual chattel.

The Australian novelist discovers his story in the apparent chasm between the author of L’Histoire de O and her creation. Dominique Aury (who wrote it under the pseudonym Pauline Reage) was serious, scholarly, demure — nun-like is how some described her — a woman who spent decades in impeccable intellectual toil at the storied publishing house of Gallimard.

But she did have secrets. Her real name was Anne Desclos (abandoned along with a failed early marriage) and the love of her life was a married man. As for the scandalous bestseller she wrote — a book that changed mores and divided the Western world — only a precious few knew she was its author for decades after publication.

The Story of O began as a series of love letters written by Aury to her colleague and lover Jean Paulhan, a publisher and critic who was a pillar of the French intellectual establishment and an early member of the wartime Resistance. Aury adored him but knew his roving eye. The story she spun was a way of using her mind to keep him erotically in thrall.

Carroll’s O takes this personal back story and treats it as narrative germplasm. Beyond the document of period pornography the relationship inspired — a tale of domination and submission, freedom and slavery — he spins a broader story about France, the war, collective trauma and nascent feminism. Salacious as its source material may be, his is an intelligent, earnest, searching novel: a book to be read with both hands.

Carroll’s point of departure lays in the balance between sex and power laid out in The Story of O. Many second-wave feminists found Aury’s novel appalling. They read it through a pornographic lens. O’s absolute submission to masculine desire could not be squared with the expansion of freedom and agency promised to women by post-war social change.

But the Australian begins from the premise that power might be as important as sex in Aury’s story. Here are the opening lines of Carroll’s novel, introducing Aury in wartime Paris on her way to a first meeting — a job interview, really — with Paulhan:

‘‘Swastikas, giant black crawling insects, flutter from town halls, department stores, government buildings and palaces. Dominique shivers at the sight of them, feels them on her skin, scuttling over her face and neck and arms.’’

Carroll wants us to appreciate from the outset that the Nazi aesthetic — its uniforms and flags, leather boots and crops — are fetish images of pure force. The invasion and occupation of France should be regarded as the primary violation, Indeed, this is how the French perceived their situation in 1943, at least according to Dominique, who later happens across an illegal poster that depicts France as a prostitute: ‘‘France, a tart with her legs open, staring up at the sky while a foreign army marches all over her. Pétain, the ubiquitous, avuncular pimp who handed her over.’’

Just as Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini drew on the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom in Salo, his final and hugely controversial film about fascism in wartime Italy, Carroll deploys the Sadean pitilessness of Aury’s novel (Paulhan was an admirer of De Sade’s writing) to connect the personal with a moment of utmost political extremity.

First, though, Carroll fleshes out the imagined (though biographically informed) story of Dominique and Jean’s lifelong relationship. That initial interview at a Parisian café is a moment of charged acknowledgment.

Aury, then in her early 30s, divorced and with a young child, not beautiful but highly intelligent, recognises in the older Paulhan another creature who, beneath the bourgeois trappings, is capable of wildness.

Their affair, begun soon after, bears out her intuition. It gains a dangerous edge and piquancy, both from its adulterous nature (Paulhan is married, his wife an invalid) and the clandestine work for the Resistance in which Paulhan involves Dominique.

She starts with pamphlet drops then moves on to editing manuscripts by Jewish authors for the underground publisher Editions de Minuit.

Eventually Dominique is summoned to a meeting, one where Paulhan is present but, crucially, is obliged to hand his lover on to other men.

They recruit her for an emergency mission: to assist in the evacuation of a Frenchwoman who, having taken a German officer as a lover on instructions, has been passing on information gleaned from their pillow talk. Her cover has just been blown.

In this section, as quietly thrilling in its way as Army of Shadows, Jean-Pierre Melville’s classic film account of the Resistance, Carroll reverse engineers the origins of The Story of O. Pauline Reage (a fabricated name in truth) is introduced as a real character. She is the uncommon beauty Dominique must escort to safety.

During their short, concentrated acquaintance, Domonique is made privy to Pauline’s tearful admission: she fell in love with the German officer. Reage admits shame at this betrayal of country by her solitary heart, a confusion that lodges deep in Dominique’s imagination.

When, later, Aury borrows the woman’s name as a pseudonym for The Story of O, it is without fully understanding how much more she has borrowed from Pauline’s experience.

More clarity is gained by an event that comes at the conflict’s end. Celebrations break out spontaneously across the city as Paris is liberated by Allied forces. Church bells ring and champagne flows. Recriminations almost immediately follow.

When Domonique happens across a naked woman on her knees — bloodied, terrified, a swastika crudely drawn on her shaven skull among a group of drunks — she is roused to furious defence. Those who presume to judge her now were not the kind to fight when it counted, she knows.

But two things about the situation surprise Dominique. The first is that the woman seems unbowed by the attack: ‘‘ … as much as the prostitute is docile, there is also something deeply unsettling about her: as though, there in all her degrading submission, her casual audacity, there is this disturbing sense of power, an insolent cheek …’’

The second is that once rescued and away from the gang, the girl makes clear that she deserves the treatment meted out to her. The punishment was not warranted, but it was desired.

All of these memories flow back into the postwar sections of Carroll’s novel. The Story of O is no longer, in the Australian’s telling, merely the effort of a woman in love to titillate her lover. It is the distillation of those aspects of the occupation which remain — for Aury, for Paulhan, for French society in the round — unresolvable paradoxes.

That erotic novel, which seems so dream-like and outside of history, actually corresponds to the period when she and Paulhan — wise, dangerous owl to her black cat — were ‘‘inhabitants of [a] hazy time, the blue hour, that is neither day nor night, blurring the distinctions between everything’’.

Despite Carroll’s efforts to ground his version of this story in larger context, a danger remains: there is still no gainsaying the absolute submission of O that Aury describes in her novel. The argument against the novel from feminist perspectives remains live. The book wears the inexpungeable stain of scandal. It has been banned; it has been burned.

Carroll’s response is to inhabit Aury’s mind with as much care, intelligent sympathy and respect as he can muster (Paulhan remains shadowy in comparison).

He makes sure that readers recall that she began the book as a challenge: Paulhan really did tell Aury that no woman could write a book like De Sade’s Sodom. She proved him wrong, triumphantly.

Moreover, Aury’s wartime experiences — those moments when she tested body and will against the might of the occupying forces — render the question of censorship, who may write and what they may write about, sinister and absurd.

As Carroll has Paulhan put it, with hard-earned dignity: ‘‘We must show the world that we have not all bowed down before the new masters. That we are still us. Still standing. Still part of the world: this free world we helped invent. And we must show them we are ready to fight for it. Show the world that we publish who and what we choose to publish.’’

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout