Michael Finkel’s book explores the life of hermit Christopher Knight

Why would a person choose to spend 27 years alone in the woods? He spoke just one word in all that time.

“His seclusion was not pure, he was a thief, but he persisted for 27 years while speaking a total of one word and never touching anyone else. Christopher Knight, you could argue, is the most solitary known person in all of human history.”

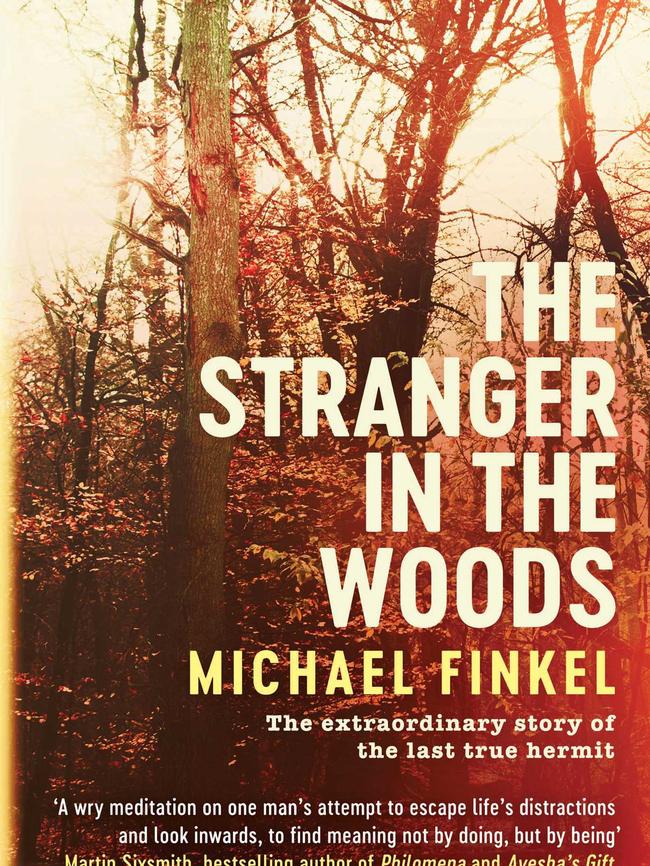

That’s a good description of “North Pond hermit” Christopher Knight in Michael Finkel’s fascinating book The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit (Simon & Schuster, 203pp, $29.99). It’s good because it describes Knight but does not answer the question any reader will ask: Why did he do it? Nor does the book, despite Knight being its main source. And that makes it even more intriguing to read.

The one word Knight spoke in 27 years, by the way, was “hi”. He said it to a hiker who crossed his path. Then he fled, and worked out how to hide even better.

I first learned of Knight a couple of years ago when Finkel wrote a story about him for GQ magazine. When I learned Finkel had turned the story into a book I was excited. As someone who likes solitude and values silence, I wanted to read about a man who, in this day and age, chose a life that took such preferences to an extreme level.

As such, I was on his side. I suspect I’m not alone in being attracted to this sort of thinking: “It’s possible Knight believed he was one of the few sane people left. He was confounded by the idea that passing the prime of your life in a cubicle, spending hours a day at a computer, in exchange for money, was considered acceptable, but relaxing in a tent in the woods was disturbed.”

But it’s not as simple as that. As mentioned earlier, Knight stole — from holiday cabins and from a charity-based camp for disabled people — to stay alive. He took mainly food but also more expensive items such as gas tanks, pots and pans, tools, torches, radios, car batteries, clothes and even a TV at one point. He pocketed cash now and then — $US395 in total over 27 years — but not expensive items such as jewellery or computers. By the time he was caught in 2013, he had committed more than 1000 break-and-enter robberies. He said he was ashamed of them, pleaded guilty and spent almost a year in jail. He had psychological tests that, while not definitive, do suggest some reasons for his behaviour.

He hated prison because it was full of other people, though his spirits lifted when he was moved to a single cell. In letters to Finkel, who initiated contact, he said he coped by reducing his vocabulary to just five words, spoken only to guards. He added a comment that might provide some insight into his personality: “I will admit to feeling a little contempt for those who can’t keep quiet.”

Knight comes across as intelligent to the point of arrogance. He’s well read (he stole a lot of books). It makes me laugh when he’s asked about noted transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, who lived in a Massachusetts cabin for two years, an experience that produced his famous book Walden. “Thoreau,” Knight declares, “was a dilettante.” Knight’s favourite book is one I admit to liking too, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, with its isolated and bitter narrator. He also likes Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, though I suspect he wishes Friday would go away.

Knight did not record his own experiences. He didn’t write poems. After his arrest he did not speak publicly, though he was billed as “the most famous person in the state of Maine”. He had no interest in changing the world beyond his own. “I wasn’t consciously judging society or myself. I just chose a different path.”

Knight, who was raised in Maine, was 20 and working in Massachusetts — as an alarm installer, which would come in handy later — when he drove home, parked his car at the edge of the woods and walked in. It was 1986. Ronald Reagan was US president and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster had just happened. Neither was the reason he went wild. He had no plan, or supplies. “It was as if he went camping for a weekend,” Finkel writes, “and didn’t come home for a quarter century.”

Knight came from a solid rural family, with four brothers and one sister. He would not see or hear from any of them for a long time. “To the rest of the world, I ceased to exist,” Knight says. Well, not quite. When his father died 15 years later, Knight was listed in the obituary as a living son. His mother never gave up hope. Her son, now in his 50s, lives with her.

Knight tells Finkel he has thought a lot about why he did what he did. His answer: “It’s a mystery.”

Knight isn’t fond of being described as a hermit, though he accepts it’s an accurate use of the word. He didn’t look like one — he shaved every day and wore decent (purloined) clothes — and he was no pillarist or anchorite. He didn’t meditate. He wasn’t religious. His camp was only minutes from people, hence the closeness of properties to burgle, but so well hidden as to be inaccessible to anyone but him, a man who had woodcraft skills that impressed even the police. When Finkel visited it, his mobile phone worked fine.

Knight lived in a large tent and slept in a bed. He read, he listened to the radio. He knew what was going on in the world. He wore the same glasses he was wearing when he was 20. He says he never fell ill because “you need to have contact with other humans to get sick”. He was often hungry, but when he had food he was able to cook it. He was often cold. There’s a funny moment when Finkel asks him how he avoided the vicious mosquitoes that plague the area. Some Arcadian nostrum perhaps? “I used bug spray,” Knight replies.

He is wryly amused about being thought of as a “warm and fuzzy person, filled with friendly hermit wisdom”. That very image goes to how some locals responded to their mysterious loner. They left bags of food on their front steps, or a notepad on which he was invited to write down anything he needed. Maine is used to odd characters. Others, particularly families with young children, were scared of the man who haunted the woods. They thought of him hiding behind a tree, watching them. They feared he’d sneak into their homes while they were sleeping. There was talk of poisoning him, or setting bear traps.

There was — and remains — a theory that Knight was not a hermit at all. That he had help from family members or friends, that he spent winter living in empty properties. That is one of the questions about Finkel’s book: the hermit tells the story. It’s his version of events. The author does try to get inside Knight’s mind, but that is hard work. Finkel does offer some context by considering other historical hermits, but this feels a bit like padding.

As the “reign of the hermit” continued — and became more brazen — residents started to “hermit-proof” their properties with deadlocks, alarm systems and security cameras. And so it was that one night in April 2013 Knight was nabbed by the local lawman. The story of Knight’s return to the world is just as absorbing as the story of his time away from it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout