Menendez brothers speak out, 35 years after they killed their parents

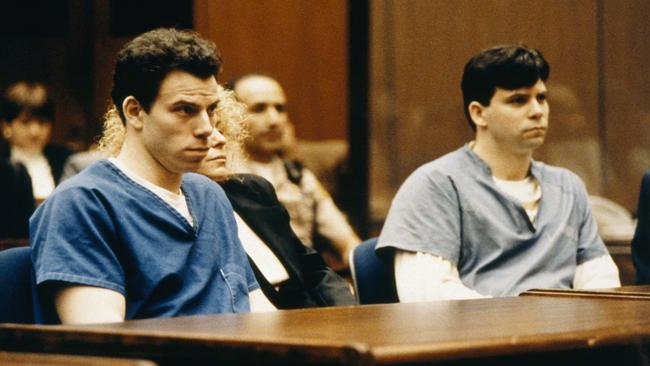

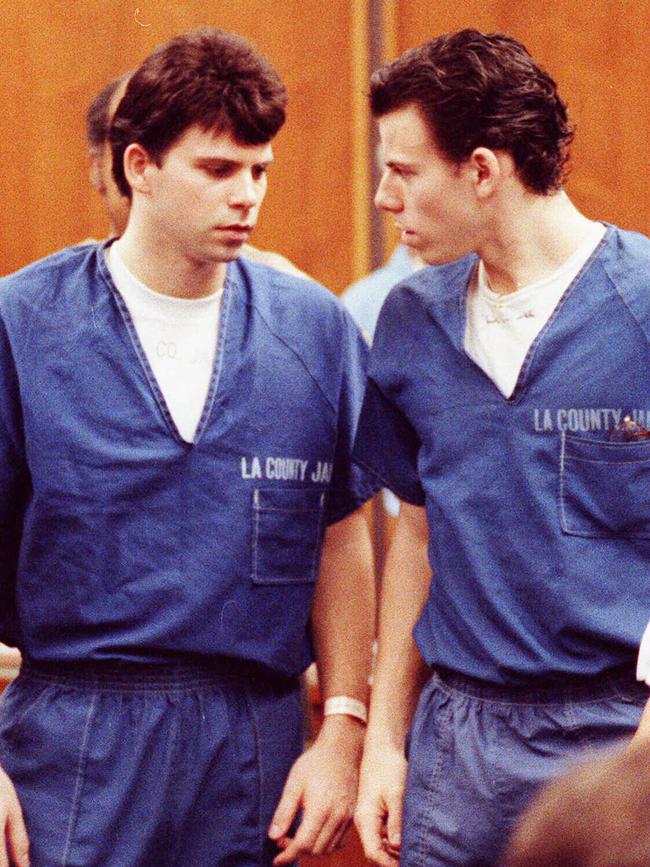

A Netflix series and documentary have revived global interest in Erik and Lyle Menendez, who blasted their allegedly abusive parents to death with shotguns while they sat watching TV in 1989.

In 1995 the Los Angeles trial of the Menendez brothers was “the talk of the town” according to Vanity Fair, that self-described cultural barometer, “because it’s the best show in town”. According to the magazine, “People begin lining up at four in the morning to be sure they get in – the way they do for Academy Awards night”.

On August 20, 1989, using shotguns, these entitled young men killed their wealthy parents, Jose and Kitty, at close range in the den of the family’s Beverly Hills home in salubrious Elm Street, while they were eating ice cream and watching TV.

The brothers purchased the guns just days before the shootings in San Diego where they used false IDs. They confronted their parents and fired 14 blasts, Lyle shooting his father in the back of the head, the mother still alive after several shots. Lyle went outside reloaded, came back and he said, “Shot her close.” The gun barrel was on her skin when he fired.

Afterwards they partied, gambled, and went happily on pricey shopping sprees, buying Rolex watches and expensive cars.

Despite talk that it had been a Mafia hit, they were eventually arrested after confessing to their therapist and accused of first-degree murder. Going on trial, the proceedings were televised by Court TV, a media newcomer at the time.

It was argued by prosecutors the brothers killed for financial gain; the defence, while admitting they killed their parents, contended it was self-defence. Their principal argument that the boys believed they were in imminent danger after years of emotional, psychological, and sexual abuse by their father.

The first trial, the focus of such celebrity fascination, with the boys swaggering, strutting, and smirking at the start, found the jury deadlocked; a retrial was held, the defence’s evidence of sexual impropriety excluded, and the Menendez boys were convicted of first-degree murder.

Now 35 years after they killed their parents the boys are back in the public eye following the huge success of Ryan Murphy’s Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story. Still trending on Netflix, it’s a complex piece of Murphy storytelling, fictionalised to some extent while based on extensive research, campily exaggerated at times and oddly comic, but often highly moving. Like anything Murphy touches there’s that affinity for the theatrical. He revels in the juxtaposition of the beautiful and the ugly and violent.

And, of course, the series has generated not only controversy but sparked yet new interest in the fate of the brothers. “I think there’s a case to be made that everybody involved is a monster,” the director says in response to criticism of his series. “You know, the brothers certainly did monstrous things, the parents reportedly did monstrous things, and it was complicated. I’ve always wanted to do a season about something that had sort of a Rashomon approach where you took all of these different theories or conspiracies and you weave those through the narrative, and this show just had so many of them.”

He believes that’s why Monsters has created such controversy and confusion about the choices he and co-writer Ian Brennan made “The truth of the matter is these were things that people thought and were presented in court and were written about as fact. So, they’re not my facts or my opinions. It was stuff that was in the court of public discourse. I wanted to write about that. I was interested in how complicated it all was.”

As Murphy has suggested in several terse interviews, his show has given “these brothers another trial in the court of public opinion”. The controversies ignited by his show parallels the years of the Menendez brothers being championed by TikTok and Instagram creators calling for their release. The call to have them retried for manslaughter rather than murder has become widespread in some quarters as a result of a growing social understanding of the traumas suffered by abuse victims, including men.

Now Netflix, as if determined to add even more substance to calls for the judicial system to rethink the fate of the brothers, or as many claim simply to cynically attract eyeballs and take advantage of the continuing outrage, has just released a documentary called The Menendez Brothers. Its aim is to provide another more personal perspective on the events.

The director is Alejandro Hartmann, who directed the Netflix documentary The Photographer: Murder in Pinamar, an account of the brutal murder of photographer Jose Luis Cabezas in the summer of 1997.

It’s from Ross Dinerstein’s Emmy-winning Campfire Studios, and Dinerstein is a co-producer with Rebecca Evans. His company is responsible for around 70 factual series and movies, including The Innocent Man, an adaptation of John Grisham’s only nonfiction book, which contributed to a federal judge overturning the wrongful conviction of Karl Fontenot and Tommy Ward after 36 years behind bars.

“The first trial was a hung jury,” Dinerstein told The Hollywood Reporter. “It was not something that a jury of their peers was able to convict them on, and it was almost retried for a whole new generation in real time, and people were very emotional about it.” He was explaining the way when Court TV re-aired the first trial during the pandemic, it alerted a new generation to the possible inequities of the case, generating the TikTok social media movement.

And his series, based on interviews from prison by the Menendez brothers, is largely in the form of what’s become known as exoneration true crime. The idea is to take up the cause of wrongfully convicted victims, shedding light on possible miscarriages of justice, highlighting flaws in legal systems. Think of Ken Burns’ The Central Park Five, The Staircase or Making a Murderer.

As Lili Loofbourow wrote recently in The Washington Post, “These shows aim to generate righteous uncertainty, often casting the perpetrator’s sentence – or the process that put him behind bars – into question. Viewers are treated as co-investigators rather than passive consumers of closed cases. They might learn a little history as they watch.”

And Hartmann, rather clumsily it must be said, re-examines the experiences of the brothers, exploring the larger social context though the commentary of various talking heads, and scrutinises the way the LA justice system responded to extralegal pressures when the city was in a state of chaos.

Within a pretty standard format following a rough timeline, Hartmann talks to prosecutors, exasperated family members, expert witnesses, jury members who have written books, and journalists, who have also written books. And because of the self-promotion of some of Hartmann’s witnesses there’s a sense of satisfaction – almost glee in the case of a former juror – at being involved.

There’s a great deal of archival footage – especially coverage of the tearful brothers’ court testimonies – and Hartmann gives some context to the #MeToo-inspired push for reconsideration of the case in the light of changed attitudes to traumatic abuse.

At the centre of his film, of course, are the odd-sounding statements of the brothers, now in their 50s, recorded over the wonky prison communications system. They took place it seems after they reached out to the producers, according to Dinerstein, when they became away of those agitating so vocally for their release.

The taping happened over five months and the brothers certainly sound sad, sorry, personally reconstructed, and forthcoming about what Erik calls “the sick secrets of the family”. As well they might, given that they, to some extent, set this film up, and Hartmann is hardly the most rigorous interviewer, barely raising a difficult question. The best interview is with the feisty prosecutor Pamela Bozanich. “I’m telling you now, that whole defence was fabricated,” she says. “And if I were an immoral person, I would have fabricated it much the same way.”

And at the end of her sitting she’s equally adamant.

“The only reason we’re doing this special is because of the TikTok movement,” she says. “If that’s how we’re going to try cases why not we just have a poll. You just vote on TikTok, and everyone gets to go home. Your beliefs are not facts – they are just beliefs.”

Murphy, too, has signed off. “The Menendez brothers should be sending me flowers,” Murphy told The Hollywood Reporter. “They haven’t had so much attention in 30 years.”

The Menendez Brothers is streaming on Netflix.