Martin Amis, The Rub of Time: Essays and Reportage, 1986-2016

Donald Trump has dispensed with shame, writes Martin Amis. He’s proved an American can now go all the way without it.

Even if you were to take Martin Amis’s fiction off the table, you could still plausibly claim him as the Anglosphere’s most interesting living writer. Look at what he has produced, in the various departments of nonfiction, since the turn of the millennium. You have Experience (2000), the gravid memoir; The War Against Cliche (2001), that endlessly nourishing book of literary criticism; Koba the Dread (2002), his controversial monograph about Stalinism; and The Second Plane (2008), an indispensable collection of post-9/11 political pieces.

And now we have The Rub of Time, his strongest collection of nonfiction to date, a feast of a volume that brings together his hitherto uncollected essays, reportage and reviews.

All of Amis’s usual interests are here, along with some new ones. There are meditations on his favourite writers (Saul Bellow, Vladimir Nabokov, Philip Larkin). There are pieces on sport and popular culture, including some wonderfully funny stuff on tennis. And there are bang up-to-date appraisals of US and British politics.

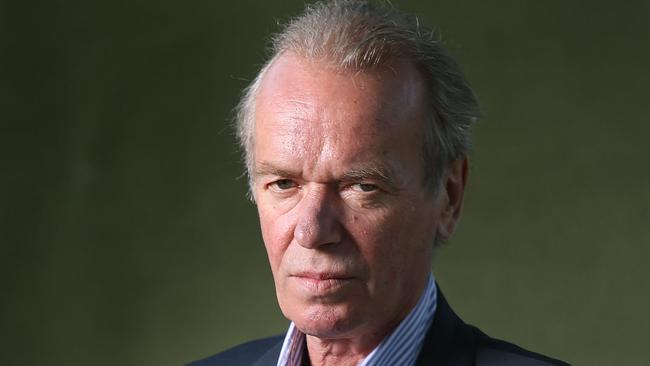

Attacking these questions from the vantage point of his maturity, 68-year-old Amis confirms his status as one of literature’s great exemplary all-rounders: always stylish, always deeply intelligent, always voraciously interested in the world around him.

Sprawling and various as it is, the new book keeps returning to two linked themes: masculinity and excess. And a good half of it zeroes in on the place where these themes achieve their most startling expression: the US.

None of this will surprise the long-term student of Amis’s fiction, which has been probing these connections since his breakthrough novel Money (1984). The narrator and protagonist of that book, the cashed-up philistine John Self, was addicted to the modern world. That meant he was addicted, above all, to America.

Starting with Self, Amis’s characters have always been hopping on planes and flying to the US. And Amis has always been flying there too. Finally, in 2012, he stopped flying back to his native Britain and settled in Brooklyn, New York. And why not? “America,” he writes in this book, echoing Henry James, “is more like a world than a country.” What better place for the international writer to base himself?

Amis has already published one collection of nonfiction about America: The Moronic Inferno (1986), the resonant title of which he borrowed from his mentor Bellow. The best pieces in the new book revisit the inferno and find that it has grown no less moronic. The clinching essay, written at the height of last year’s election campaign, concerns Donald Trump: a man who embodies the inferno so thoroughly that he wears it as a hairstyle.

What is it about the US, exactly, that keeps stoking the fires of Amis’s imagination?

There is a clue, I would suggest, in the following passage from The Information (1995), another novel in which the central character takes a life-altering flight to the States, where he encounters, among other grotesques, a woman named Phyllis.

In person, Phyllis seemed to be the kind of American woman who had taken a couple of American ideas (niceness, warmth) and then turned up some dreadful dial, as if these qualities, like the yield of a hydrogen bomb, had no upper limit — the range had no top to it — and just went on getting bigger and bigger as you lashed them towards infinity.

Lashed towards infinity: it could be the title of the present book or of the next biography of Trump. Amis is not anti-American; far from it. But he is old school enough to assert that some things do have upper limits. Decorum, he is in the habit of saying, must be observed. Which means the satirist in him loves it when decorum is violated, the more floridly the better. Hence his ongoing preoccupation with the US; its dreadful crankings-up of the dial, its lust for the infinite.

Take pornography, which Amis does in this book, by paying a visit to the San Fernando Valley, home of the American hardcore industry. How does pornography crank up the dial? By making itself more erotic? Emphatically not. It does so by becoming nastier: more sordid, more violent, more degrading to the female participants.

Amis, who loiters on the set of a gonzo feature until he can take no more, offers all the grim specifics. These would make for a rough read if the author didn’t introduce an uncharacteristic note of warmth in the person of an “unforgettable” local porn star named Chloe, who serves as his guide through the valley of filth, his bawdy Virgil. Chloe is an improbably self-aware and ironic porn star; if she didn’t exist, Amis would have been embarrassed to invent her. Since she does, he is free, indeed obliged, to use her humanity as a counterpoint to the squalor of her milieu.

In his fiction, Amis has a natural tendency to heighten and exaggerate. His nonfiction plays it straight, since the realities it deals with tend to be exaggerated already and often downright unbelievable. Reporting from Porn Valley, Amis achieves comic effects by simply offering up the facts in deadpan fashion.

Mind you, the comedy is a deep shade of black. When a performer named Regan Starr complains of being violently assaulted during a porn shoot, Amis give us this: “The director of the Rough Sex series (now discontinued), who goes by the name of Khan Tusion, protests his innocence. ‘Regan Starr,’ Tusion claims, ‘categorically misstates what occurred.’ ”

Like his father Kingsley, Amis is a connoisseur of language. He revels in the sobriquet of the maligned auteur, Khan Tusion; he instinctively knows that the surname must be isolated and repeated. And he knows that “misstates” is gold, too: a quintessentially American piece of pedantry that makes Tusion sound like Mitt Romney on the campaign trail.

In Porn Valley, reality is self-satirising. The same effect prevails in Las Vegas, where Amis goes to play in a poker tournament. Vegas isn’t just a made-up town. It would seem to have been made up specifically by Amis. In its casinos and fake streets, he encounters various avatars of American excess, including the morbidly obese. People’s bodies, in Vegas, “are unbounded, infinity-tending, like a single-handed push for globalisation”.

As long as he’s sailing close to the wind, Amis singles out a woman “who has munched herself into a wheelchair: arms like legs, legs like torsos, and a torso like an exhausted orgy”. Notice, if you haven’t already, the brazen censoriousness of “munched herself into”. Not many writers, these days, would dare to put it quite like that for fear of incurring the dread title of fat-shamer or body fascist. Who does Amis think he is, judging this woman he has never met?

To a writer of Amis’s generation and type, the answer to that question is straightforward. He is a moralist, a satirist, a cultural critic; his job is to register what’s wrong with society. Judging people, therefore, is his bread and butter. And he’s still at it. Evidently he missed the meeting at which it was decided that judging is no longer on. He’s still cracking jokes, too, another problematic activity given that humour, as Amis himself once pointed out, always entails an assertion of superiority.

Pushing his luck in two ways, Amis is always getting himself into public scrapes. There is a piece in this book about Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the British Labour Party. In it, Amis observes, or claims, that Corbyn is “undereducated”. When the piece first appeared in print, that word earned Amis a brief spell in Britain’s naughty corner. Columns were written in which he was accused of snobbery, elitism and other crimes against advanced mores.

Writers of such columns, however, will always be at least one move behind Amis. He already knows what they think and what they will say; his prose is already a reaction against their strictures. One of his key virtues as a writer is the seriousness with which he takes his vocational obligations.

He knows our culture is full of people who want to shrink the domain of the sayable. And he knows that one of the writer’s duties is to push back the other way: to establish what can still be said, if necessary by saying what can’t be said. If writers such as Amis don’t resist the incoming tide of old and new taboos, who else is going to? Alas, that question has already been answered, at least in the US. Suddenly the world has Trump. After the cult of compulsory respect, we have the cult of in-your-face boorishness. Amis deplores both tendencies with equal staunchness, without having to vary his principles to do so.

His critics, on the other hand, are required to keep two sets of books here. When Amis went on record denouncing Trump’s “cornily neon-lit vulgarity”, few newspaper columnists, to my knowledge, accused him of snobbery. Suddenly they were on his side. They saw the point of elitism after all.

Amis, the man who invented John Self, is well qualified to analyse Trump. Unsurprisingly, his analysis starts with Trump’s verbal output, before broadening into a more general indictment. Reviewing Trump’s latest book, Amis finds that his sentences “lack the ingredient known as content”. Nevertheless, they do convey a certain attitude. And that attitude clearly has its fans.

Among other things, what Trump’s election tells Amis “is that roughly 50 per cent of Americans hanker for a political contender who … knows nothing at all about politics”. What is revolutionary about Trump, to put it another way, is not his ignorance but the way he has converted it into a selling point.

George W. Bush, when he stumbled over the delivery of a simple homily, at least had the decency to look embarrassed. So did Dan Quayle when he was caught misspelling the word potato. John Self, too, had a vestigial sense of shame: he knew that all his cash did not make up for his lack of culture. Then again, Self was a fictional character; he was Amis’s fantasy of what a rich yobbo ought to feel, when his conscience finally kicked in.

Trump, on the other hand, is real. If others won’t hold him to the demands of decorum, why should he impose them on himself? Like the pornographers of the San Fernando Valley, like Las Vegas, he has dispensed with shame. He has proved that an American can now go all the way without it. This is his breakthrough.

One of the most resounding passages in Amis’s book occurs in an out-of-the-way place, during a brief chapter in which the author responds to questions from readers of Britain’s Independent newspaper. “Why are you such a snob?” one asks. After replying, first of all, that he is not a snob, in the class sense, Amis works up to this:

On the other hand, I think snobbery is due for a bit of a comeback. But not the old shite to do with “class”. “There is a universal eligibility to be noble,” said Bellow rousingly. There is clearly a universal eligibility to be rational and literate. Sometimes snobbery is forced upon you. So let’s have a period of exaggerated respect for reason; and let’s look down on people who use language without respecting it. Liars and hypocrites and demagogues, of course, but also their fellow travellers in verbal cynicism, inertia, and sloth.

Startlingly, the former enfant terrible is now a grand-pere terrible. But he is still on the cutting edge of public speech. Reading this book, I kept marvelling at what a committed writer Amis is. Superficially this seems an odd word for him since he is not committed to any simple partisan stance. What he is committed to is writing itself. He believes even the shortest newspaper piece must be written with all his formidable resources.

He is committed to his role as the autonomous, secular truth-teller, the equal-opportunity offender who answers to nobody except himself and his readers. He still seems to think that writing can change the world.

It’s a good thing he’s in career-best form. We are in no danger of ceasing to need him.

David Free is a writer and critic. His new novel is Get Poor Slow.

The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump

Essays and Reportage, 1986-2016, By Martin Amis

Jonathan Cape, 356pp, $35